One day, I quoted the following verse by poet Bhavabhūti to him.

बहिः सर्वाकारप्रगुणरमणीयं व्यवहरन्

पराभ्यूहस्थानान्यपि तनुतराणि स्थगयति

जनं विद्वानेकः सकलमभिसन्धाय कपटैः

तटस्थः स्वानर्थान्घटयति च मैौनं च भजते

[A “genius” indulges in every activity while making his adversaries unaware of even the minute flaws in his plans, he misleads others to think as though he is indifferent of the outcomes but gets the results in his favour, keeps himself silent too.]-Mālatīmādhava, Act 1, Verse 15

He listened and laughed it off. He hardly entered into any argument, dispute or challenge. During his last days, they were non-existent. One could never sense any stubbornness in his work that his opinion was always right or that it had to be complied with. Hence there was neither joy when he won nor sorrow when he lost. If he wrote an article for a magazine, he would tell the editor “use it as you please” and never troubled his mind worrying about whether it was published or not as per his wish or whether it was altered. In this connection, even if there was a blunder, he would only say “it’s alright! What to do!”, but would never become angry or sullen. Because of this, his mind remained peaceful and the other party would also be more compliant. Particularly when the other party is older, obstinate and expects compliance, there is no better way than this to please them. But not everyone is endowed with a good nature that is devoid of ego and willingness to lose for the sake of greater purpose. I have not seen someone who is this soft among any of his friends or family except perhaps his brother-in-law, Kaiwara Srikantashastry.

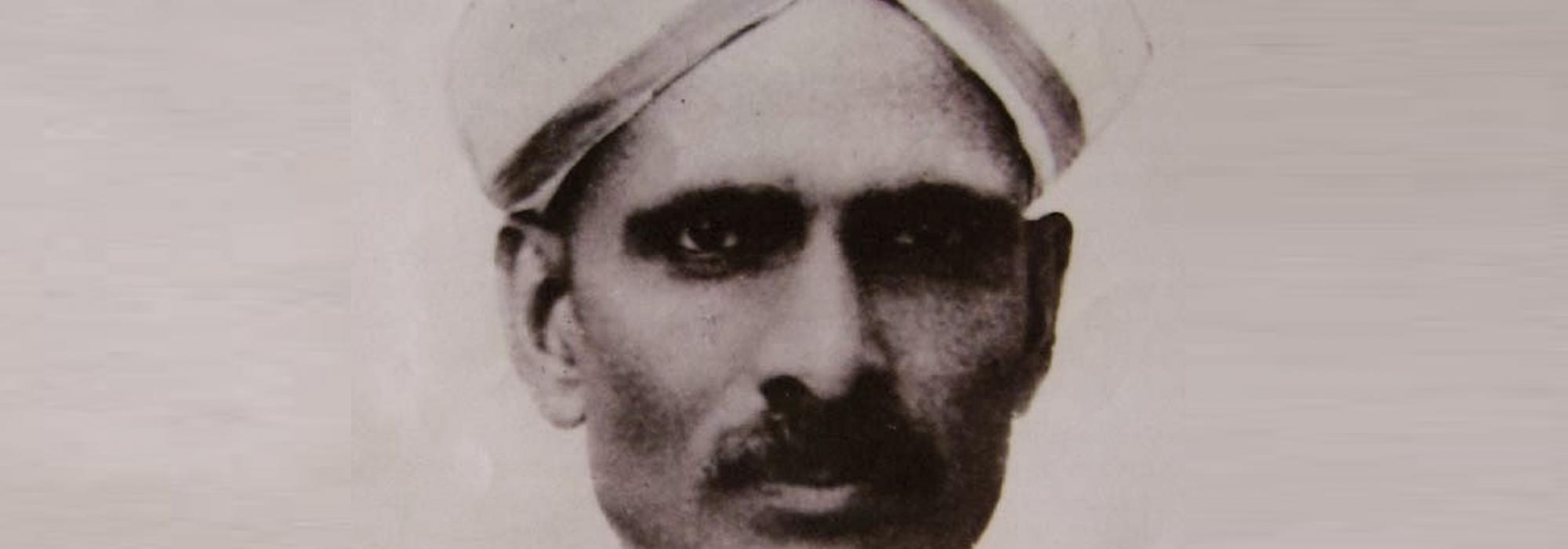

It would not be inappropriate here to give a short introduction to vidvān Srikantashastry. Because in all these - bhakti, vairagya, wisdom, worldly matters, and a spotless life - Venkannayya considered him a role model. Shastry’s picture adorned the mandāsana in the pūjā room along with the deities and pictures of the Agadi Sādhu and his student Narayana Bhagavan. Around the time that Venkannayya first came to Mysore, Srikantashastry also arrived there to study at Samskrta College, and cleared the vidvat exam in Literature. But there was never any ego that he was a vidvān. He had a broad, calm, round face, always smiling; resplendent; wide-eyed sparkling eyes. A significant quality of his, a unique quality that was a source of admiration and amazement for Venkannayya, was his accommodating nature: Whoever he was with, he would behave like them, when with them - drink coffee in the company of coffee drinkers, partake naśya (snuff) in the company of snuff aficionados; even compete with them; in the company of people with no such habits, he never got the urge; in a vaidika household, he would follow all their traditions, oppattu (skipping dinner), fasting; in the company of women, conversation appropriate to them; with children, he would eat, frolic and tend to them. He never complained at any time that the food served was inadequate; never ever was angry or had a sullen face. He was like a flawless crystal. Having lost his wife at a young age, he went and joined the Agadi Sādhu, giving up any idea of remarriage. I am unaware how they came to know each other. Becoming a teacher there at the Samskrta College, in the midst of service and satsaṅga, he left behind household duties. (It is here that he translated Adhyātma-rāmayaṇa into Kannada and published it through ‘Sadbhoda-candrikā’). In the midst of all this, relatives interested in his remarriage, grumbling that their boy in the company of the Sādhu may be lost to them, came to Agadi and complained to the Sādhu. He called Shastry and commanded him saying “Shastry, you get married!”. Shastry did not disagree. The marriage took place, but its fruits were not on expected lines. Neither the couple got along well nor did the family grow. It was like one more person came and joined the one already in Agadi. I had seen him during my student days and again later, though infrequently; he lived like a water drop on a lotus leaf; adhered, but not attached; the epithet ‘jīvanmukta’ was apt to him. Apparently, his death was also befitting this description; just before dying, he sat up from his lying position, got some sugar fetched, held it in his hand, meditated with his eyes closed, distributed it to the people around as ‘prasāda’ , and laid down, wrapped. After some time, when the wraps were removed, he was no more. Venkannayya himself used to narrate this with fervor. This simplicity of his was not pusillanimity that lacked wisdom; when Venkannayya’s father passed away or perhaps when he was caught in some worldly crisis, sitting worried not knowing how to proceed, he came and chided, “kṣudraṃ hṛdayadaurbalyaṃ tyaktvottiṣṭha parantapa! Venkannayya, do you think bhagavān Krishna meant this only for Arjuna? Get up, get a grip on your mind and go on with your work!”. Venkannayya later said no one else could have advised him, and even if anyone did, it would have been pointless. Perhaps the man who influenced him in dharmic matters more than Srikantashastry was Agadi Sheshachala Sādhu. However, since I have never seen him, I have not brought up his topic here.

Venkannayya’s main tenet in life was not to hurt anybody and to please everybody. While this had the useful goal of getting work done, the principle of ahimsā (non-violence) was overriding. He would never utter anything unpleasant; but then, never a pleasant lie either. If required, he would give subtle hints, or he would just be silent - this was routine for him. If he ever got into the dilemma of having to say anything unpleasant, he would put off things blaming one of his own shortcomings, giving excuses like “I am lazy, I can’t put the effort to write” or “I just can’t remember; I forget” or “I cannot absorb anything fast; I will read again at leisure and get back” or “I am timid, can’t go and ask others”. He felt that it is bearable to tell a lie of no consequence rather than lose affection by uttering an unpleasant truth. Along with this, he had respect, devotion, humility, affection, esteem, friendship, fondness and attachment - these he used in immense measure as needed and developed close relationships. Therefore, outsiders were perhaps more devoted to him sometimes than if they were his own children. He was a living example of the saying “सन्तोषं जनयेत् प्राज्ञः तदेवेश्वरपूजनम्” Once, while in Dharwad, having sent away all people at home to another place, he had to stay alone. For nearly a month, he survived drinking a seru (about a litre) of cow’s milk during morning and evening - this avoided the inconvenience of procuring grocery and of cooking; it avoided depending on anyone for food or going to a hotel; at the end, it avoided the hassle of arranging vessels to heat the milk too. He used to explain this in a satisfactory and agreeable way.

Normally, nothing would agitate him; swallowing his anger, grief, and worry and digesting them with his wisdom, he was used to always being cheerful. However, during his final days, a few troubles which he could neither talk about nor suffer, nor solve, led him to rue. In 1937 some miscreants (thieves) raided his home and stole away some cash and a silver plate in which he used to dine. Even that did not perturb him; “It is alright, probably this is all I deserve; looks like God does not like me eating from a silver plate”. However, he had a strong feeling that a difficult phase had started from then onwards; “Somehow, there is no peace of mind; it doesn’t crave for pūjā (Ceremonial prayer to the deities), sandhyāvandanam, pārāyaṇa (Recitation of scriptures) etc.; I have given up on them too; fate does not let me perform any of them; even my father had a difficult time once; he too went through a similar phase”, he used to say. With the hope of finding some peace, three to four months before he passed away, he had started reciting seven cantos of Sundarakāṇḍa. I learnt this when I enquired about it, after having watched him recite it, when he carried the book with him to Bangalore during that time. But when he came to Bangalore again after some time, he did not recite it;

When I asked him about it, he replied “Some mailige (such as death of an immediate kin etc..) event has taken place and I have discontinued”. Seemed like it had caused some trepidation in his mind. But that trepidation turned into a portent.

This is the second of the three-part translation of the article "ದಿವಂಗತ ಶ್ರೀಮಾನ್ ಟಿ ಎಸ್ ವೆಂಕಣ್ಣಯ್ಯನವರು" by A R Krishna Sastri which appears in the collection "ಬೆಲೆಬಾಳುವ ಬರಹಗಳು". Edited by Raghavendra G S