While discussing about mārga and deśī, the author has brought much clarity in drawing the lines of distinction between the two, and at the same time showing their merging points. Clarity on these major concepts will throw much light in the works on re-construction of techniques. Also, the realisation that mārga becomes a vocabulary with which many languages as Deśī forms may emerge (all with respect to dance in this context), will be a big revelation. The following sentences are significant for this reason.

‘Accordingly, mārga is the essence that is realised out of intense and unbiased search; it transcends time and space. Mārga is based on fundamental human nature and caters to universal experience. Deśī refers to the particular features practiced in different regions. Thus, when mārga is adapted to different regions by catering to regional tastes, it takes the form of deśī. Similarly, when deśī transcends spatial boundaries, it graduates to become mārga.’

While making a point on how and why Yakṣagāna cannot be simply classified as jānapada art, the author has defined for the first time in the history of śāstra, the most logical and profound difference between classical and folk forms. He says, ‘In jānapada art, no one is exclusively an artiste or merely a connoisseur. Everyone takes part equally in the presentation of the art. Such presentations usually do not have the five sandhis that the Nāṭyaśāstra speaks about….although there is no dearth for enjoyment and beauty in these forms of art, there is not much scope for creative elaboration as per manodharma as they lack the framework or structure provided by a śāstra… In summary, though these forms of art are exuberant, lively, simple, and attractive and may even have some layers of suggestion, they will not be able to make a deep and long-lasting impact on the audience. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the dividing line between the artiste and connoisseur almost vanishes in jānapada…keeping the aforementioned features in mind, Yakṣagāna cannot be classified as a jānapada form of art in the technical sense.’

These are the last words give concrete distinction between folk and classical forms. It may be noted that according to the concept of mārga and deśī, a deśī form may be a classical form and not necessarily a folk form. The dancers must now be sure what they intend to present their forms as. With this right understanding, it is obvious that as one ascends the ladders of aesthetics, the art form progresses towards classicality only. Actually, this is a personal call of every artiste based on his or her own manodharma. Nevertheless, whether folk or classical- they have their own unquestionable place in the art world with respect to its purpose and audience. When there is clarity of these aspects, these forms will be allowed to exist in their own ways gloriously. It is not a question of competition between the two, but the question of eligibility and affinity for them that makes the actual difference between the artistes and the art forms.

In another context, the author states a mahāvākya about nṛtta. He says, ‘Nṛtta should be rooted in Sāttvikābhinaya, even though it is non-referential in nature. If not, it is akin to rusted iron that has not come in contact with a divine gem that can bestow holistic charm.’

These statements speak volumes about the nature of ‘desirable nṛtta’ for the dancers. Unfortunately, many dancers presume that nṛtta is a mere technical exercise. This has happened so much so that nṛtta is performed only to prove technical ability and ‘vastu’ based abhinaya is performed for their own joy (they fear that the audience may not understand). There is a false notion that nṛtta is enjoyed better. When a true connoisseur is asked, we understand that the technicality of nṛtta too is beautiful only when the technique takes the matured form of transcendence of grammar and realised in Sāttvika abhinaya which leaves no distinction between the body and heart of the artiste. So also, the ‘vastu’ based abhinaya compositions too are most desirable if loka-dharmī is blended with nāṭya-dharmī with propriety, giving it the magical touch of a picturesque communication and beyond that, sheer enjoyment!

Another of my favourites is this statement by the author-

‘Change in the field of art is rather slow and gradual. Art should always remain true to Rasa and therefore changes cannot happen at high rates.’

This statement is a warning and a guideline to a true seeker of art in form and purpose. It is very difficult for an artiste especially, to be to one’s own self. This is because of the nature of art itself which takes ‘world’ to be the raw material. Hence artistes are easily deluded and run outwardly much more than it actually needs. Though it is very difficult to perceive where exactly is the line of saneness to this, it may be understood that ‘observation’ of the world and not ‘indulgence’ into it-is what is actually needed for an artistic vision. Classical art demands a more inward journey than an outward one. The nature of Rasa experience being a ‘reflection of Brahmānanda’, demands nigraha (restraint and withdrawal). This is the true test of eligibility to seek and practice classical art.

The amount of philosophising that has gone into these articles as penned by the author, tempts me into more and more indulgence on the discussion of these concepts. But after a point only silence speaks more than words, for these statements of the author be better contemplated upon than excessively discussed.

I shall end this section with a quote by the author on Sāttvika-abhinaya.

‘The emotion that needs to be artistically presented should firstly be internalised by the artiste. He must fully experience the emotion. Then doing away with his ego, he must bring out the emotion in a creative manner. This is the real job of an artiste…the difference between āsvādaka (the experiencer) and āsvādya (the thing to be experienced) disappear and only āsvāda (experience) remains. This kind of experience is Rasa. It is only through Sāttvikābhinaya that such experiences can be achieved in art.’

V

One of the best articles of the book is the one titled, ‘Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna: The Concept, in Practice and Philosophy’.

This article is very special because the concept of Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna is the author’s own brainchild. When a new concept is being introduced, there are many challenges that surround it. The author has ruthlessly intellectualised this methodology of pratipādana for this form, that any honest and genuine artiste should embrace this without any reluctance.

The terminologies that are fascinating for the technical enhancement through appropriate usage are the terms ekahārya and eka-bhūmikā (single actor, single character), bahvāhārya and bahu-bhūmikā (multiple actors and multiple characters); the most interesting add-on, is the term ekāhārya coined by the author. It means that a solo artiste is performing and donning a single costume throughout. These terminologies give a lot of scope for various permutations and combinations for various forms of nṛtya and nāṭya, especially with respect to the contemporary classical dance forms in comparison with the rūpakas and upa-rūpakas of the past. The author also analyses the value of nṛtya-nāṭakas too on these lines. Such technical jargons are helpful in giving precision to thoughts and interpretations and the scope of the meaning implied, during a serious analysis of a subject. For this reason, these terms have to be necessarily applied in technical conversations and writings.

There are some wonderful insightful claims that the author makes with authority and authenticity about why and how the technique of āṅgika, vācika and āhārya were conceived. The nature of the plots selected are also convincingly justified. Some of the quotes are mentioned to have a glimpse of this content. However, I sincerely confess that it is impossible to exhaustively record even the most important thoughts, as the entire article is pervaded with such insights.

- This form of solo Yakṣagāna focuses on depth rather than width and establishes the sthāyi-bhāva of the particular character extremely well.

- However, if we were to develop this as a dance form, the strengths inherently present in Yakṣagāna will not be showcased. Impromptu abhinaya, extempore delivery of dialogues, and being true to character portrayed-these features would be lost, should we employ the genre of nṛtya.

- It is difficult to bring in arthālaṅkāras to nāṭya-sāhitya, especially when they must be set to tāla and are rich in śabdālaṅkāras. Therefore, abhinaya and melodic singing have to make up for the missing arthālaṅkāras… The three guṇas-ojas, prasāda and mādhurya have also been used appropriately as required by the context and emotion. In these compositions, the pān͂cālī-rīti is predominant and gauḍī and vaidarbhī rītis can be found at certain places. The compositions used for Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna are poetically much more beautiful compared to the compositions meant for other forms of classical dance.

- The best form of art unravels itself when the citta-vṛttis themselves become the itivṛttas. We also wanted to elevate śṛṅgāra from the physical plane to the emotional plane…. I always wanted to compose poems that can bring out all the subtle beauties of śṛṅgāra.

- Bhāminī is the story of our own lives. Our desires, successes and failures, highs and lows of our moods are all captured here. All of us are Bhāminīs in one sense or the other. We are under the mercy of our desire-husbands, who at times cater to our emotions and at other times fail to do so. We fight with our desires-sometimes win and sometimes lose. There is scope for evoking all the nine Rasas here. When our desires are fulfilled, it leads to śṛṅgāra, hāsya or adbhuta. When they fail us, it leads to karuṇa, vīra, raudra, bībhatsa or bhayānaka. Śānta is inherent in all these emotions. This can easily be correlated with the Bhāminī production…. She has now won the love of her husband and is thrilled- a svādhīnapatikā. This is the dharma of companionship – dāmpatya-dharma……the wife can even grow to be a mother of her husband. The goal of Bhāminī was to depict such subtle śṛṅigāra – one can even call it the śṛṅgāra-dharmopaniṣat.

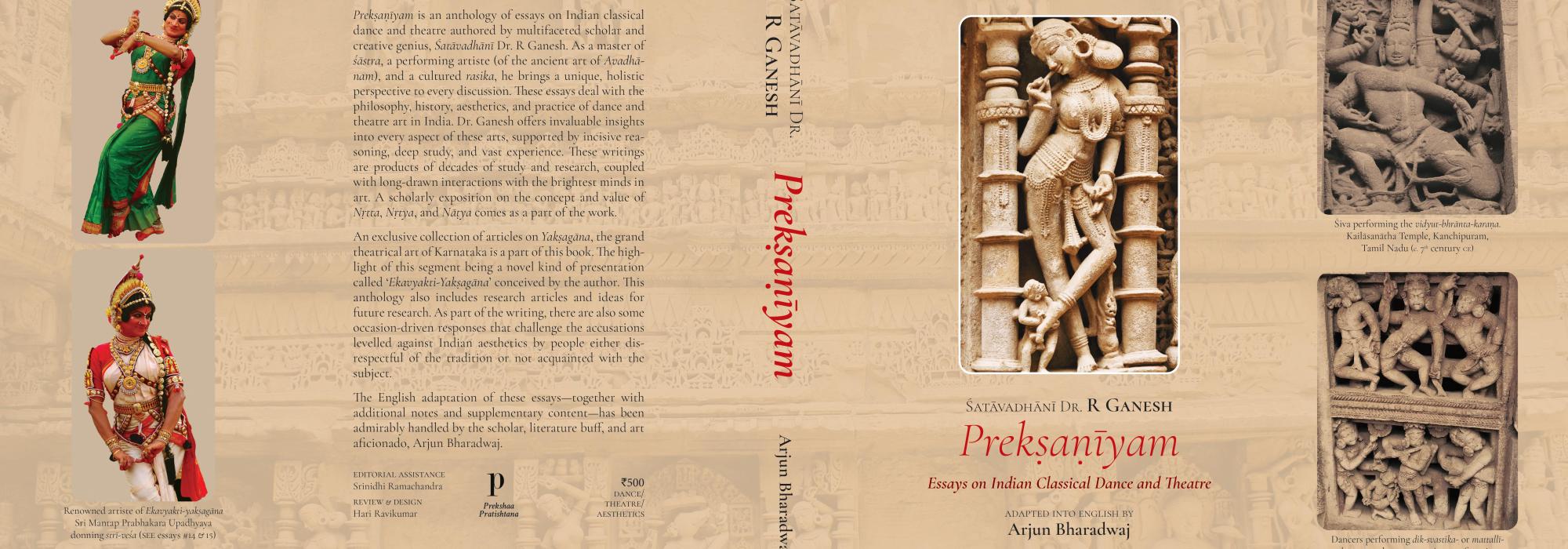

I am at loss of words to express the length and breadth of aspects that get beautifully unveiled on their own accord in the course of the flow of this article. First is the point that any new form when evolved for the first time is never welcomed by peers and critics. But it is absolutely the responsibility of the creator of the form to justify why at all such form was needed and how it is unique and deserves to be created. The author has done this so meticulously that it is logically and spiritually (from the perspective of sattva-spirit of a being) difficult to deny his argument. The next challenge is to provide the quintessential of the form. Here too the creator wins the bet-the caturvidha-abhinaya technique has been exhaustively taken care in the shaping of the grammar which has been elaborately dealt in the article. The most difficult challenge is that of aesthetics which had to be justified only through performance. Whenever a lakṣana is evolved consciously for a lakṣya, it is the burden of the lākṣaṇakāra to justify the lakṣaṇa in the lakṣya. The extraordinarily talented Mantap Prabhakar Upadhyaya has fulfilled this challenge too by making lakṣya an experience; in fact, he has made lakṣya the basis to go back and enhance the lakṣaṇa. The author has very highly spoken of this artiste for bringing in life and justifying the whole process of evolution of ekavyakti-yakṣagāna through his gratifying performances. I too, having witnessed the artiste par excellence, am in total agreement with the author.

The most profound aspect of this article is the visualisation of śṛṅgāra-rasa itself. The last few quotes mentioned above is the acme of the philosophy of śṛṅgāra. If not for anything else, ekavyakti-yakṣagāna is a fulfilling journey for the profundity in content and all aspects of technique that have humbly subserved this very purpose. It is not an exaggeration to say that other than personal reasons (which can never be resolved with technical handling of the form), there does not seem to be a big opportunity for disagreement with the concept and presentation of ekavyakti-yakṣagāna.

VI

One of the biggest attractions to my own self and am sure to many researchers in the field, is the brainstorming article titled- ‘Research in Dance-Possibilities and Challenges’.

It is breath-taking to wade through these pages. I wonder what should be the nature of the intellect of this person who can see the grossest of the gross to the subtlest of the subtle. When researchers are wondering if classical arts have scope for research in the truest sense, the author has given an inexhaustible list of topics pending to be researched. For decades together, even if an army of researchers is employed to research on these topics, it would not be enough. Such is the length, breadth, and the width of vision for research in Dance in this essay. One can only fathom how many such topics can be seen as parallels in music, painting, and sculpture-in general the fine arts category.

Here are some samples to the ‘wonder’ points made.

- For all dance-related research, it would be good if movement vocabulary is held as the focal point. Research in the realm of grammar is useful but research in the domain of the content is far more important.

- All forms of art turn towards philosophy when their content is taken up for discussion. Thus, philosophical perspective is inevitable for the analysis of the content of all forms of art. All other research is at the structural level.

- When dancers start contemplating upon the content, they must consciously and critically examine their own experiences.

Honestly speaking, the entire article without exception of even a sentence is invaluable to an earnest reader and researcher. But this also comes with my disclaimer that to see such extraordinary vision in the article for the reader, he should truly be a connoisseur of dance and desperate for embracing such profound possibilities. The long list of prospective topics which have been classified, also mentioning the scope for research under each of such classification is truly a feast to the intellect! One has to resort to the book to truly enjoy this variety.

VII

The article titled- ‘Dr. Padma Subramanyam’s Contributions to Indian Values and National Integration in the context of the Dravidian Movement’ which is co-authored by Dr. Ganesh and Arjun Bharadwaj has well captured the legend’s contributions and documented the essence of her lifelong sādhana in classical dance. This article will be a pramāṇa for her work that has indispensable and eternal value to the field of classical dance. Dancers will ever be grateful for this article which is an exhaustive documentation.

Conclusion

If I claim that my experience with Prekṣaṇīyam is invaluable to me, then I have to express my gratitude to Sri Arjun Bharadwaj who has translated with authenticity, responsibility and with a sense of uncompromising keenness to reach this profound writing of Dr. Ganesh to the prospective readers. For this job to be done with this impact, it needs the scholarship, calibre, and depths of the author himself. The translator has proved his might in this capacity through his work of translation. Dr. Ganesh’s language in Kannada is melody to ears, but the same is a mighty rival to confront when it comes to translating it. I can only imagine the endless efforts of Arjun to achieve this quality of translation. I also acknowledge him for the meticulous work that has gone into adding additional footnotes, exhaustive indices, glossary etc., to make this a reference material for students from the point of view of data, besides the inspiration that the author has left dripping in every sentence of the book. I gratefully appreciate Sri Arjun Bharadwaj for this work on behalf of the dance fraternity for giving this reach to the work.

With a confession that only kāvya which takes refuge in vakrokti can satisfyingly state the experience that this book has given me, I rest my meagre attempt to give a glimpse of the contents of this book. I humbly admit that even to enjoy the reading of these pages of the book and pen a few words about this priceless content, I have been equipped by none other Dr. Ganesh himself through his mentorship over the years, which I have been blessed to have. However, with the very strength of receiving such mentorship, I claim that every word penned by me is because of the meticulous intellectualisation that sprung from the logic of form to content, and not because of mere emotional outburst. I am convinced experientially and intellectually to make the statements that I have made in the course of my writing.

I wish this writing of mine on Prekṣaṇīyam will instigate my readers to read the book in entirety and also experience the joy that I have been bestowed with!