Music Practice

In 1909, during the birth anniversary ceremony of Krishnaraja Wodeyar III, there was a music recital by Bidaram Krishnappa in the Royal Court of Mysore. Upon listening to him sing, Sarma was enchanted. The dormant desire to learn and practise music was activated. For several years, Sarma had learnt music from Karigiri Rao and Chikka Rama Rao and was in constant touch with the musical luminaries of that time such as ‘Vīṇā’ Sheshanna, ‘Vīṇā’ Subbanna, Mysore Vasudevacharya, [Harikeshanallur] Muthaiah Bhagavatar, etc. Sarma had to spend more time on his lectures at the college and so his interest in music had to be sidelined for some time.

Sarma’s body and voice suffered when he was affected by the influenza pandemic in 1918. Heeding to the advice of his doctor, he suspended his training in vocal music and started learning the violin. He was deeply pained for having to distance himself from singing.

I am reminded of an instance that illuminates his character. He had heard a beggar sing Nāda-sudhā-rasambilanu, a kṛti composed by Tyāgarāja, in the Ārabhi rāga. Although the text of the song was available, the tune was not so well known in those days. Sarma jumped out at once to fetch the beggar. Sarma made him sing the song four to five times and then learnt that song. He was told that the beggar had learnt that song from his mother.

The song that Sarma thus learnt, he sang before Muthaiah Bhagavatar, who subsequently popularized this attractive piece of music by teaching it to all his students.

The Post of Telugu Paṇḍita

The modern education ‘system’ had remained out of Sarma’s reach. But this vacuum was filled at an opportune moment—circa 1910—when Sarma got introduced to C R Reddy, Professor of English and Philosophy at the Maharaja’s College, Mysore.

By then, C R Reddy had already read and appreciated Sarma’s collection of poems such as Pènukoṇḍapāṭa, Śamīpūja, etc. Reddy used his influence in the Maharaja’s College and helped Sarma secure the post of Telugu paṇḍita [i.e. Telugu tutor.] Sarma worked as a Telugu teacher for about thirty-eight years and retired in 1949.

When the Master of Arts (MA) course in Kannada was started in Mysore University in 1927, it was mandatory for the students to learn another South Indian language. B M Srikantayya often favoured Tamil, at least in the early years. The reason most of the students opted for Telugu as the second language was because it was being taught by Sarma.

K V Puttappa (Kuvempu), G P Rajarathnam, D L Narasimhachar, M V Seetharamayya, T S Shamarao, B Kuppuswami, and several others were all Sarma’s students when they studied MA (Kannada) in Maharaja’s College. Further, G S Shivarudrappa, M S Venkata Rao, and a few others would frequent Sarma for the study of Sanskrit kāvya literature. Sarma had several ‘Ekalavya’ students from Andhra Pradesh as well.

Mastery in Teaching

To teach the poetry of Tikkana (a famous Telugu poet) such as Udyoga-parva in the Kannada medium, it is necessary to have an authoritative hold on both languages. Sarma was proficient in both these languages and as for Sanskrit, it was as familiar to him as his mother tongue.

K Venkataramappa, a Telugu professor himself, has recalled that he had requested the students of the college to ‘approach Sarma to understand the meaning’ of a certain sentence in Pārijātāpaharaṇa, a Sanskrit work. He further recalled, “Be it prose or poetry, Sarma enjoyed it and made the students enjoy it too. Paṭhana (recitation), padaccheda (splitting of the words), anvaya (prose ordering), artha (word-for-word meaning), tātparya (overall import), vyākaraṇāṃśa (elements of grammar) alaṅkārāṃsa (figures of speech and other literary embellishments) – all these were taught not only systematically but also in an attractive manner by Sarma. He was a born orator. He would first explain the subject in Kannada and then systematically analyse the Telugu works further. He had an amazing ability to make even the most complex issues sound simple. He would anticipate the doubts the students would get on any given lecture and would clarify those beforehand. Therefore, there was no necessity to ever approach him with doubts. On some rare occasions, if one were to approach him with doubts, he would clarify them with a great amount of patience, irrespective of whether he was approached inside or outside the classroom.”

Many of his students have fondly recalled Sarma’s mastery in teaching. Recalling that he was never late to a class, D Javaregowda said, “By reading a padya or two, he made the students travel back in time to the world of the poet. He liberally used the Kannada and English languages in his lectures and stamped the subject in the minds of the students. We would realize that we had completed one hour of his lecture only when he stopped speaking!”

Even a great musical exponent like Bidaram Krishnappa greatly respected Sarma and would call him ‘Paṇḍita.’ He was thus widely respected.

Sarma had great affection towards his students. However, this did not entitle them to any discounts while learning. A V Krishnamacharya was learning the violin from Sarma. Once Sarma had asked Krishnamacharya to come early the next morning because he wanted to teach him some complex movements on the violin. When Krishnamacharya came early the next morning, everyone in Sarma’s house was still asleep. Sarma opened the door, asked Krishnamacharya to be seated, washed his face and sat down to teach him. Sarma taught for over two and a half hours. Even so, there was no sight of dawn in the east. Krishnamacharya grew suspicious about the time and then looked at the clock. It was not even half past three in the morning! He had hurriedly come to take lessons by one in the morning. Sarma had a smiling face even then.

Contentment

Although he had the post of a lecturer on paper, that hardly filled his pockets and hence the daily issues never subsided. By the age of eighteen, even before he had started working in the college, Sarma was married. The distressed life of those times flowed in the form of a poetical work Bhārgavī Pañca-viṃśati, which when discovered by a well-wisher, took the form of a publication that fortified the status of Sarma in the gallery of poets. The lines of that work, “I don’t seek, O Mother, material benefits; I only seek your blessings so that I may lead a dignified life!”[1] demonstrates the aspirations of a matured mind.

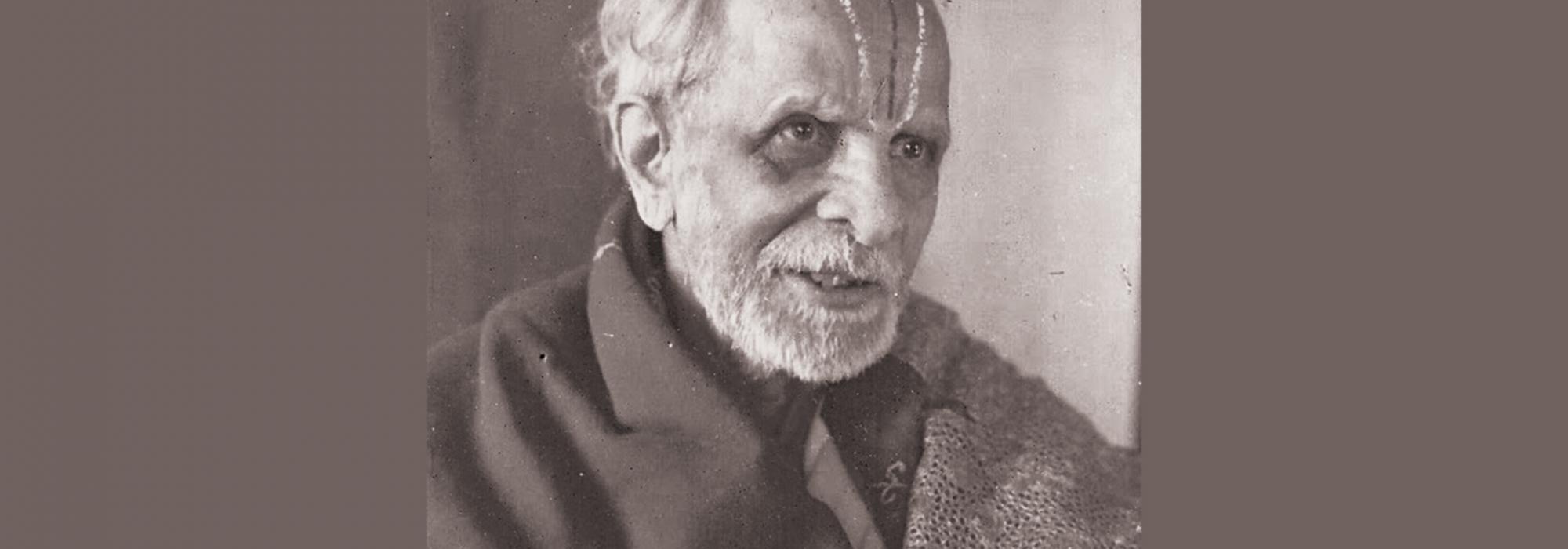

There were several people who were ‘professors’ of English, Persian, Arabic, and other such languages in the university but there was only one Rāḻḻapalli Ananthakrishna Sarma who was a ‘paṇḍita’ of Telugu and retired in the same post.

This never drove him to complain about a position that he ought to have got. When my friend Dr. T V Venkatachala Sastry raised the topic of Sarma not being promoted despite serving for such a length of time, he was quick to forbid such a thought. He said, “Why attach importance to my case? Did Hiriyanna[2] enjoy the fruits of his labour?”

Sarma was nominated as a special member of the Kendra Sahitya Academy and an appointment letter was issued to him. Looking at this, Sarma said, “At my age, this is more of a burden and less a matter of happiness. I am unable to travel to Delhi to receive this honour that is bestowed on me. Even if I am able to, what use would it serve?”

To be continued...

This English adaptation has been prepared from the following sources –

1. Ramaswamy, S R. Dīvaṭigègaḻu. Bangalore: Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana, 2012. pp. 122–55 (‘Rāḻḻapalli Anantakṛṣṇaśarmā’)

2. S R Ramaswamy’s Kannada lecture titled ‘Kannaḍa Tèlugu Bhāṣā Bèḻavaṇigègè Di. Rāḻḻapalli Anantakṛṣṇaśarmaru Sallisida Sevè’ on 11th July 2010 (Pāṇyam Rāmaśeṣaśāstrī 75 Endowment Lecture) at the Maisūru Mulakanāḍu Sabhā, Mysore.

Thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for his review and for his help in the translation of all the verses that appear in this series.

Edited by Hari Ravikumar.

Footnotes

[1] ‘Gauravaṃbuna jīviṃpa nanugrahiṃpu madiye pūrṇaṃbagun bhārgavī.’

[2] Prof. M. Hiriyanna was one of the greatest authorities on Indian Philosophy and his works are revered and read by scholars even to this day.