Visit to Oxford

Soon after Dr. Shantaram Kane ('SK') told us about the episode of Dr. P V Kane ('PVK') being appointed Vice-Chancellor of Bombay University, he was reminded of a similar incident. In 1937, PVK had visited Europe when his son—i.e. SK’s father—was studying at the Imperial College, London. While he was in Europe, PVK visited several leading universities such as Cambridge and Oxford and had discussions with the heads of Departments of Oriental Studies. On learning about PVK and having interacted with PVK for a few days, a certain professor, who was the Head of the Department of Oriental Studies at Oxford suddenly asked PVK how old he was. “I am fifty-seven. Why do you ask?” The professor then told him that he was thinking of retiring and would like to propose PVK’s name to the university authorities as his successor. PVK thanked the professor and then asked him, “How can I manage this post given that I’m a practicing lawyer at Bombay?” The professor said that he knew of the courts in India having summer vacations for three months in a year and PVK could spend that time at Oxford. The professor was also gracious enough to make an offer to PVK that he need not spend the entire year at the university. The post of Head of the Department of Oriental Studies at Oxford was obviously a coveted position and a huge honour. However, PVK felt that such an assignment would rob him of the considerable time he would otherwise get during the summer, to work on his magnum opus. He politely declined the offer. SK’s father found out about this the next day, but having once said ‘No,’ it was impossible to make PVK go back on his words and take up the offer.

Association with the Bhandarkar Institute

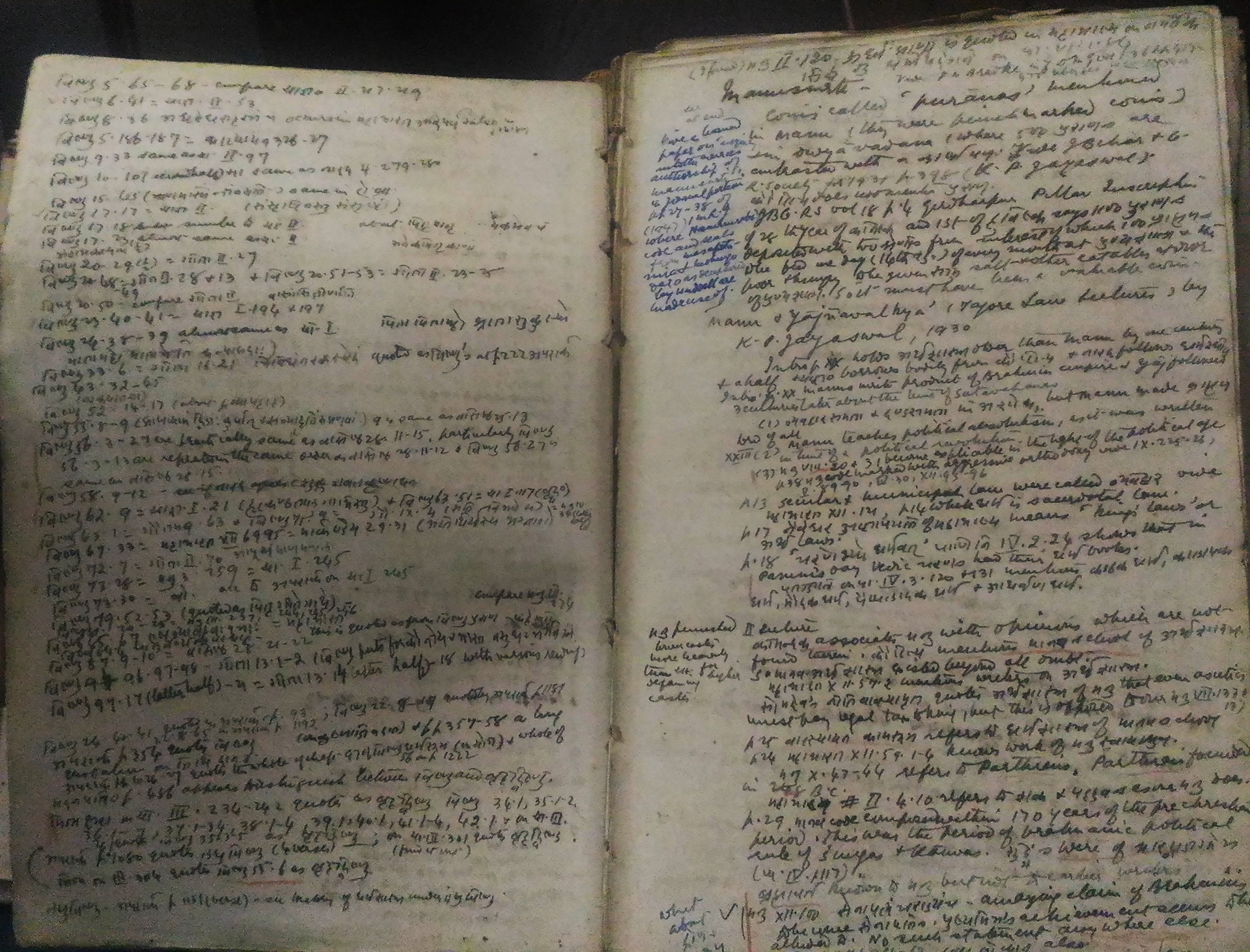

In the course of our study of the History of Dharma-śāstra, Dr. Ganesh had told us that PVK had more than a hundred notebooks filled with his notes, which he used while writing the volumes. I asked SK if he had those notebooks. To our dismay he didn’t. He said, “I was in the US when my grandfather died and it was only much later that I came back to India. My father and my uncles were alive at that point of time and I thought they might have preserved what they found useful. During those days, we did not realise the importance of holding on to these things and I really do not know where they are. Perhaps the Royal Asiatic Society has them, but I’m not sure. However, I have preserved the first printed edition of the History of Dharma-śāstra, which contains my grandfather’s remarks, corrections, notes, etc.”

We jumped out of the seats in surprise and requested him to show us. He smiled at us and was very kind to guide us to his library in the upper floor of the apartment, where the first edition books were carefully stored. The pages of course were extremely delicate, and we had to handle the book with utmost care. PVK’s notes were in the first few pages of the book and in the middle of the paragraphs in the printed pages so as to make those edits for the next edition.

PVK’s first edition books and his marginal notes gave us a sense of industry he had put into the work and to the extent of detailing made therein. I asked SK about how this book was received by the publishers – Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI). The answer was on expected lines; the publisher was more than happy to publish this monumental work of a great scholar and it was not in the minds of the publishers that this work would be profitable. The work was great and had to be published. That was the main aim in BORI publishing this work. We slowly made our way back to the lower floor of the apartment and got seated. SK then told us that PVK was one of the persons who was instrumental in setting up the infrastructure for BORI. PVK and his friends—totally thirty of them—all of whom were scholars and were involved with BORI in one or the other way, bought thirty acres of land in Pune. Each one had contributed money for an acre. Out of this, they donated fifteen acres to BORI for building the present magnificent building. In the remaining fifteen acres, they kept half an acre each for their residential purpose. But PVK never built on this land during his lifetime. This piece of land was gifted by him to his two sons. SK’s father then left his share to SK and his sister where they had an apartment complex built. And it was in one of the flats of that very apartment we were presently seated. Then it made sense to us that BORI (where we had gone the previous afternoon to buy books) was located within half a kilometre from the apartment.

I asked, “Why didn’t Dr. Kane build anything here?” SK said that during PVK’s lifetime, this was almost on the outskirts of the city and it was not prudent to build a house at that spot. Moreover, PVK lived in Bombay throughout his life.

Property at Dadar

Our conversation turned to PVK’s house in Bombay. “Could we possibly visit the house of Dr. P V Kane in Mumbai, where he stayed, studied, and wrote the History of Dharma-śāstra?” To our surprise, SK told us that PVK stayed in a rented accommodation in a chawl in Bombay from 1898 till his passing away in 1972. That rented accommodation was later returned by PVK’s heirs to the landlord. So there was no question of seeing PVK’s house. The three of us looked at each other in shock and then one of us asked, “Did Dr. Kane stay in a rented house throughout?”

“Yes, those days there were two-room tenements (what we call ವಠಾರ in Kannada) available for rent. Tenants would stay in a place for decades. My grandfather had taken four tenements on rent, used them as a single house and stayed there. It was in a chawl in Girgaum, which was a mile away from Malabar Hills and that’s how he would go for a walk everyday there. It used to be in the heart of the city those days,” said SK.

Hari, who was parallelly taking photographs of a few books on PVK using his phone, casually remarked, “Oh ok. I never knew that. I always thought that Dr. Kane stayed in his own house.” SK then told us, “My grandfather did have a property of his own. It was in Dadar. He had built a residential house with his savings. When it was completed around 1930, he wanted to move there, but his wife refused to leave their present house. She said that the city was full of life in the house where they lived and going to a place in the outskirts of the city, like Dadar, would put an end to her social life! This sound argument of his wife made my grandfather continue in the rented accommodation. He gave his Dadar house for rent to somebody.”

But the story doesn’t end there. Many tenants changed but none would pay the rent on time. When PVK’s clerk went to receive the rent, they would cry about their financially difficulty. PVK, being the magnanimous heart he was, would not pester his tenants; he would waive arrears of rent and never initiate any proceedings against them for eviction. After nearly two decades, maintaining the property and collecting the rent had become an issue. It was a huge waste of time. PVK decided that the property had to be sold. He called the contractor who used to look after the repairs of the house and told him to find a purchaser. The contractor brought the first prospective customer. In 1955, that property at Dadar was well within city limits. PVK told the prospective purchaser that he had spent a certain amount towards purchasing the plot and building a house [in 1935] and he wanted the same amount! The customer’s jaws dropped. He said, “Are you sure that is the price?” When PVK replied in the affirmative, he took out his cheque book from his bag and immediately wrote out a cheque for the said amount in favour of PVK.The house was sold. Before the possession was handed over and the sale deed was executed, PVK’s daughter learnt about his non-existent business sense and gave him an earful. “Why would someone sell the property at the price he bought it? Do you know what are the rates at Dadar now?” PVK heard all of this and calmly said, “I have given my word and I will not go back on it. I never built that house with a profit motive. By God’s grace I have a good income and I’m still in active practice. Why should I think of money in everything I get associated with?”

Well, there’s very little anyone could have said to that!

To be concluded.

My heartfelt thanks to Dr. Shantaram G Kane, the grandson of Dr. P V Kane, for sharing so many wonderful anecdotes about his grandfather with me and my friends. Further, he promptly reviewed the present essay, offering wonderful suggestions as well as fact-corrections. I wish to express my thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh and Dr. S L Bhyrappa for encouraging me to record the highlights of my meeting with Dr. Shantaram Kane. Thanks to Hari Ravikumar for his thorough editing of the essay.