The two children who were born to Satyavatī passed away at a young age. Satyavatī was saddened, thinking about her responsibility towards the lineage of her parents and husband. She called Bhīṣma and said, “O Bhīṣma! As you see, King Śantanu’s lineage has ended with you. You’re well-versed in the Vedas and the Vedāṅgas; you also have a good understanding of dharma. So I repose faith in you and will tell you something; you should carry out my request. My son and your younger brother, Vicitravīrya, left this world without begetting children. His wives, the daughters of the king of Kāśi are beautiful damsels, in the prime of their youth; they desire to have children. Thus you must beget children through them and save our family from extinction. This is also your duty, your dharma; and it is my wish as well. Along with that, get coronated and rule the kingdom; carry out a family life; don’t let down your ancestors!”

Bhīṣma replied, “Mother! What you have said is certainly in line with dharma but you’re also aware of the oath I took in exchange for your marriage (to my father). I will reiterate the same: I shall give up the lordship over the three worlds, and if there is something greater than that, I shall give up that as well, but I can never give up my integrity!”

She said, “I’m aware of your honesty. I also know the oath you took for my sake but please consider this as āpaddharma (the course of conduct during difficult times). Please execute my request, which will save our family and make our relatives happy!” She tried to convince him in different ways. In response, Bhīṣma said, “In that case, O Mother, I shall suggest a means of making sure that Śantanu’s lineage grows; and the means is also in line with kṣatriya dharma. You may discuss it with the learned and the purohitas who understand āpaddharma well. Please take a decision after discussing it with them: you can invite a brāhmaṇa of good character and noble deeds, you may pay him a fee, and make Vicitravīrya’s wives beget children through him!”

Satyavatī betrayed signs of laughter as though in agreement with Bhīṣma’s words. Shy and embarrassed, she said, “What you say is right. I shall tell you something, reposing full faith in you. It is impossible not to speak about it under the current circumstances; such is the calamity that has befallen us. Our family’s dharma, truth, and direction - all are rested solely in you. Please hear this and then do what you deem right. My father had reserved a boat to be used only for dhārmic activities. My youth was fresh and young. Once, the sage Parāśara wanted to cross the Yamunā. As I was ferrying him across the river, overcome with desire for me, he started cajoling me with sweet words. I was scared, on the one hand, of being cursed by him and on the other, of my father’s censure; I was also lured by the boons that he promised. That being the case, he took control of me, a young maiden, with his radiant power. It is because of him that I lost the foul smell of fish and was endowed with such fragrance. Kṛṣṇadvaipāyana Vyāsa was born then - the one who reorganized the Vedas. He is a tapasvi with an impeccable character; he is honest, peaceful, and sinless. If you agree, we can ask him; he had promised to come to my help, when I was in need.”

Soon upon hearing the name of the great sage, Bhīṣma said with folded hands, “This is in line with dharma and is also good for our family; I am in agreement with your proposition.”

Satyavatī thought of Vyāsa and he appeared. Upon his arrival, Vyāsa was cordially seated and after an exchange of pleasantries, Satyavatī said, “Dear son, children are born out of father and mother. Just like a father is revered by the children, so is the mother. You were born to me as my eldest son, out of divine ordinance and Vicitravīrya the youngest.[1] Gāṅgeya (Bhīṣma), adhering to his oath isn’t agreeing to have progeny or ruling the kingdom. Thus, out of consideration for your younger brother and for the perpetuation of the lineage, keeping in mind the good of all living beings and for the governance of the kingdom, please carry out my wish. Your brother’s wives are in the prime of their youth and are endowed with the beauty of divine damsels; they wish to beget children in a dhārmic way. Please have children with them!”

Vyāsa agreed to his mother’s words. He said, “So be it! Let them (Vicitravīrya’s wives) follow a strict vrata as I recommend; by doing so, they will be purified. Thereafter, they can beget children who are as capable as Mitrā-Varuṇa.”

Satyavatī did not want to wait that long; she said, “This country does not have a king; a kingdom devoid of its king will also be devoid of rain and divine grace. Thus, what is to be done, needs to be done immediately!”

Vyāsa replied, “Well then, we will do as you wish. If they need to have children before the time is ripe, they will need to tolerate this crude form of mine; that is a vrata in itself. Let me know if they can tolerate my physical form, attire, and smell.” Saying so, he went away.

Satyavatī then spoke to her daughters-in-law in private and convinced them. Once Ambikā had completed her ṛtu-snāna (‘menstrual bath’), she said “Ambikā! Tonight, your brother-in-law will come to you, be awake!” Listening to Satyavatī’s words, Ambikā thought of Bhīṣma and other men of the Kuru lineage. She stayed awake, keeping the lamp burning. At a certain time at night, Vyāsa came to her. She was stunned looking at his unkempt hair, sparkling eyes, and grey hair. Shocked and unable to bear his sight, she closed her eyes.[2] Similarly, when Ambālikā looked at him, she turned pale. In the course of time, a blind son was born to Ambikā (Dhṛtarāṣṭra); a pale and anaemic son was born to Ambālikā (Pāṇḍu). Looking at the baby that was blind in both eyes, a distraught Satyavatī tried convincing her elder daughter-in-law to conceive once again. Although Ambikā pretended as though she agreed with her mother-in-law’s proposition, she felt distasteful thinking of Vyāsa’s physical form and smell. So she summoned her dāsī (servant-maid), decked her with her ornaments, and sent her to Vyāsa. The dāsī got up with respect as soon as she saw Vyāsa approaching her, and took care of him well. The two spent the night in bliss. They too had a son (Vidura[3]).

Bhīṣma took care of the children[4] and had their saṃskāras performed at the right time. He also had them trained physical exercise, archery, horse riding, itihāsa, purāṇa, nīti-śāstra, Vedas, and Vedāṅgas. Pāṇḍu gained expertise in the art of archery. Dhṛtarāṣṭra gained renown for his immense strength. Vidura gained respect as one well-versed in dharma. In this manner, the lineage of Śantanu that had been destroyed came to life again. Since Dhṛtarāṣṭra was blind, Pāṇḍu became the king.

In time, Bhīṣma wanted to get Dhṛtarāṣṭra married to Gāndhārī, the daughter of King Subala, and sent word to the king. Subala was deeply concerned learning that Dhṛtarāṣṭra was blind; upon reflection, he agreed to give his daughter’s hand in marriage considering the renown of the groom’s lineage and his conduct. When Gāndhārī realized that her parents had decided to marry her off to a blind man, she blindfolded herself with a piece of cloth, forever, not wanting to enjoy the comforts that her would-be husband could not. They were married.

Pāṇḍu had two wives. The first one was Pṛthā[5], the daughter of King Śūrasena, the sister of Vasudeva, and the adopted daughter of Kuntibhoja. She chose Pāṇḍu in her svayaṃvara and married him. The second one was Mādrī; she was famous for her incomparable beauty. Therefore, Bhīṣma paid a lot of money to her father, the king of Madra, and bought her for the sake of Pāṇḍu.[6] After getting married to them, Pāṇḍu did not remain within the walls of the palace, enjoying its luxuries. As someone endowed with strength and enthusiasm, he set out on a victory march, defeating the kings of Daśārṇa, Magadha, Videha, Kāśi, Suṃha, Puṇḍra, and other kingdoms, and getting them to pay tributes to him in the form of gold coins. When he returned home victorious, he brought with him chariots and other vehicles that were filled with gemstones he had gained from his conquests, as well as elephants, horses, camels, cattle, and sheep – there seemed to be no end what he had amassed. He offered all of it to Bhīṣma and his mothers, paid obeisance to them, and honoured the city-dwellers as well as the villagers. Looking at the son who had returned safely after a successful conquest of different lands, Bhīṣma wept happy tears. Hastināpura was filled with the roaring sound of hundreds of musical instruments and kettle-drums.

One day, Pāṇḍu had gone to the forest with his wives and there, upon seeing a male deer mating with his female, he shot five arrows and killed them. The male deer fell to the ground trembling in terror, struggled for breath, and spoke in a human voice, “O king! Though you are born in a lineage of dharmātmas, why did your intellect fail, influenced by lust and greed? Destiny might cause the intellect to fail but the intellect cannot cause destiny to fail! Which heartless soul would kill a deer mating with its beloved in the forest? I moved about the forests, eating roots and tubers; in what way did I wrong you? O cruel one, you killed us while we in the midst of passionate love; you will meet your end in a similar way!” Saying so, the male deer breathed his last. Upon seeing this, the king was grief-stricken as if he had lost a kinsman. Although born in a noble clan, sinners are engulfed by the web of lust by the acts of Fate, succumb to evil deeds, and fall to the depths of misery. Though born to a noble soul, my father became a lustful sinner and died young, it is said; and in the place of that lustful man, Kṛṣṇa-dvaipāyana impregnated my mother and I was born. My mind was caught in a lowly addiction; addiction is great bondage. Therefore I shall let go of it, renounce the world, and try to attain mokṣa. I will follow the conduct of a muni, beg for my food, and perform intense tapas. I will live under the shelter of trees, without taking to heart happiness, sorrow, praise, blame, blessings, or salutations; I will live with everyone, always smiling. I will not be under the overlordship of another; I shall be free like the wind. I will conquer my sense organs and wash away my sins. Thus he thought and informed his wives of his decision. They said, “O King! You can perform tapas while being together with your dharmapatnis (lawfully wedded wives)! After all, if we desire to attain heaven, it shall be through you alone. We too shall restrain our sense organs and perform tapas wherever you shall be. On the contrary, if you are going to walk away abandoning us, then we shall end our lives at once; this is for certain!”

Pāṇḍu replied, “If that is the case, you must abandon the luxuries of the city and reside in the forests, subsisting on fruits, roots, and tubers. Wearing garments made out of bark and deerskin, immune to heat, cold, and winds, and unmolested by hunger and thirst, you must spend time doing tapas and lose attachment with the body.”

Soon after, they all donated their ornaments, clothes, and other belongings, and sent away their people to their hometown. When these people narrated the events that transpired in the forest, everyone in the kingdom felt dejected.

Pāṇḍu went beyond the Himalayan range, crossed Lake Indradyuṃna and Haṃsakūṭa, finally reaching the Śataśṛṅga mountain; there he performed intense meditation. After performing tapas there for a while, with a view to attain heaven he took his wives and went further north. The ascetics who lived in that region said, “As you go further and further ahead, on the way you will encounter several forts and mountains, the playfields of devas, gandharvas and apsaras, Kubera’s garden, a region of rivers, and mountainous caves; if you go even further, you will find regions that are eternally filled with snow, bereft of plant, bird or animal, and inaccessible to humans. A constant wind blows there. It is inhabited solely by a few siddhas and mahāṛṣis. How will you take these women to such a place?”

He said, “What else can I do? I don’t have children. Without offspring, how can one attain heaven? Just like I was born from my father’s seed, how can children be born from my seed? How is it even possible?”

They replied, “O noble man, it is possible. If fortune has to favour you, mustn’t you work for it? Invisible fruits of destiny come to those who undertake visible work! If you fulfil your karma, you shall have sons endowed with good qualities and that will make you immensely happy!”

Upon listening to this, Pāṇḍu wondered: After being cursed by the deer, how could he unite with his wives and father children? Therefore when he found Kuntī alone, he approached her and said, “Kuntī! We have undertaken many activities of dāna and dharma. We have adhered to strict rules and performed tapas. But all these do not attain sanctity unless we have offspring. You cannot have children from me but there are many ways of getting offspring; among those, the son born to one (directly) is great. But when that is not possible, as per āpaddharma, one can obtain offspring from a noble person. And such a son is even greater than one’s own son: this is the decided view of Manu. Since you cannot have children through me, I order you: try to obtain a son from an ascetic brāhmaṇa!”

She did not agree. She said, “O King! as someone who knows dharma, can you order your dharmapatni thus? Let me have children through you, in the dhārmic way. I will come with you to heaven. Even for the sake of children, I am not one who can think of another man; which man is better than you? You are a tapasvi and you can procure a son from be through your yogic power. I have heard that a king by name Vyuṣitāśva gave birth to children through his wife, even after his physical death.[7]

Pāṇḍu replied, “What you say is true, indeed. But Vyuṣitāśva led a life like the devas, the immortals. In the past, dharma was not this rigid either. Women had more freedom. Nevertheless, from times immemorial, it was expected of the wife to adhere to her husband’s words, especially in matters connected with begetting children; I am now commanding you: Beget children in the manner I suggest and let me attain the world that men who have fathered children attain!”

Then, Kuntī said the following words that were good and pleasing to her husband: “When I was young and was still at my father’s house, a brāhmaṇa by name Durvāsa visited us. He is known for his anger. I served him with a lot of devotion. Impressed, the sage taught me a mantra. He said, ‘The demigod you invoke with this mantra will immediately come to you and will submit himself to you.’ It looks like it is time for me to put the mantra to use. As per your command, I shall invite a devatā using that mantra and will request him to bless us with a child. Tell me, which devatā should I invoke?”

Pāṇḍu said, “O beautiful one! Please invite Dharma then. He is the most virtuous among the devatās. We will not be subject to adharma if he comes to us and the world will also see this as a dhārmic act. The child born out of him will never go against dharma.” Accordingly, Kuntī invoked Dharma and gave birth to Yudhiṣṭhira.

To be continued...

This is an English translation of Prof. A R Krishna Shastri’s Kannada classic Vacanabhārata by Arjun Bharadwaj and Hari Ravikumar published in a serialized form. Thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for his thorough review and astute feedback.

Additional segments from the epic and notes by the translators have been added in the footnotes. Apart from reading through the Critical Text of the Mahābhārata, the Kannada translations of Ka Sri Nagaraj, Devashikhamani Alasingacharya, and of Bharata Darshana Publications as well as the English translations of Kisari Mohan Ganguli and Bibek Debroy have been consulted in the preparation of this series.

Footnotes

[1] Satyavatī tells Vyāsa, “Just as Bhīṣma is Vicitravīrya’s brother from his father’s side, you are his brother from his mother’s side!”

[2] After Vyāsa unites with Ambikā, Satyavatī asks him if Ambikā will give birth to a great son. Vyāsa sees the future with his divine sight and predicts the birth of a son who will be blind. Satyavatī is worried, as a blind person cannot occupy the throne and asks Vyāsa to grant the Kurus another son. She sends him to Ambālikā. Similarly, Vyāsa foresees that the child born to Ambālikā will be diseased. Distressed, Satyavatī again requests her older daughter-in-law Ambikā to conceive. But, Ambikā, disgusted sends her dāsī, clothed in her royal garments and decked with ornaments, to Vyāsa.

[3] At this point, Vaiṣampāyana narrates the story of the sage Māṇḍavya and why Dharma was born on earth in the form of Vidura.

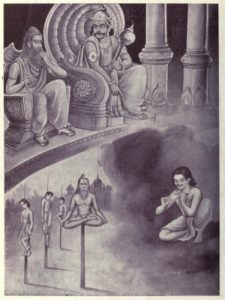

Once, there lived a pious brāhmaṇa by name Māṇḍavya. He stood in silence, with hands folded and raised up and constantly performed tapas in front of his āśrama. Once, a gang of thieves who were being chased by the king’s soldiers hid themselves and their loot in the sage’s āśrama. When the soldiers asked him the whereabouts of the thief, the sage remained silent. The soldiers found the thieves in the āśrama and suspecting the sage’s role in thievery, arrested him too. The king ordered the thieves and the sage to be stuck on the tip of a spear and killed (śūlāropaṇa). While the thieves died, the sage Māṇḍavya remained alive, seated in deep meditation on the tip of the spear. After a few days, the king noticed this, realised his mistake and decided to release him. The king had the spear cut, but could not remove the portion of the spear that had entered the sage’s body. The sage, thus, came to be called aṇi-māṇḍavya (aṇi = iron). The sage went to Yamadharma and asked him what was the sin he had committed to be punished so. Yama replied that, as a boy, the sage had poked the hind part of butterflies with a blade of grass. As the punishment is always magnified compared to the sin committed, the sage was subject to the śūlāropaṇa. The sage was enraged and cursed Yama “You have punished me for a deed that I had committed at a young age. You will be born to a śūdra woman on earth for this mistake. Here onwards, a mistake committed by a boy below the age of fourteen will not be considered a sin”. Yama was thus born as Vidura on earth.

[4] Bhīṣma raised them as if they were his own sons.

[5] Pṛthā, of matchless beauty, was born to the Yādava king Śūra (the father of Vasudeva and paternal grandfather of Kṛṣṇa). Śūrasena gave away Pṛthā to his friend Kuntībhoja, who was childless. Once, when Sage Durvāsa visited their house, Pṛthā (also called Kuntī) took great care of him. Impressed, he granted Pṛthā a mantra by which she could invoke any demigod of her choice. Though she was still a maiden, smitten by curiosity, she invoked Sūrya, the Sun deity. He appeared before her and through their union, a child was born. Before departing, Sūrya restored Kuntī’s virginity. Afraid of what the world would think of her, she placed the infant in a basket and set it afloat in the river. A (a charioteer – he was serving Dhṛtarāṣṭra) found the child in the river. The sūta, Adhiratha and his wife Rādhā raised the child. Since the baby was born with riches, he was called Vasuṣeṇa; he later became famous as Karṇa.

[6] Vidura was married to the daughter of King Devaka.

[7] Here the stories of Vyuṣitāśva and Uddālaka are mentioned.