Bidaram Krishnappa (1 September 1866 to 29 July 1931)

In about 1915, I’d been to Mysore on some work. Then the (Mysore) Palace Controller Ballalacaru Ramakrishna Rao sent for me when he learned that I was in town.

R: You must come for lunch tomorrow afternoon. I’ve some work with you.

Me: I’ll be leaving for Bangalore tomorrow afternoon.

R: That can’t happen. Go day after. Don’t argue now.

Unwilling to refuse an elder, I agreed and accordingly, at about six the next evening, went to the Sri Rama Mandira where he was staying. The building was opposite the Hardwick College. The Sri Rama Mandir was vast. There was some random conversation there for about half an hour.

Ramakrishna Rao knew a lot of tales from the olden days. He used to speak with great mirth. He was partial towards people endowed with good conduct and had a friendly nature. He had great regard for scholarship. Several scholars used to visit him for casual chatting.

After some small talk, I asked him, “you said there’s some work, please command me, what is it?”

Immediately two Vaidikas (Brahmins whose vocation is to conduct rites and chant mantras on occasions like Upanayana, weddding, and so on ) present there stood up and with the Akshata in their hand, chanted an Ashirwada (Blessings) Mantra. Ramakrishna Rao placed a bundle of books before me.

“You must take this. That’s your first task. The second is different.”

I untied the bundle. Four volumes of the Srimad Ramayana. I was elated. Ramakrishna Rao said: “Keep this for you everyday recitation. It has been thoroughly researched and excellent interpolations have been appended to it by Pandits. This work has been undertaken at the order of the Khavand, His Majesty. An order to give a copy to you has been issued by His Majesty."

Before I got this one, the copy of the Srimad Ramayana that I had with me was in Telugu script: the volume was huge in size. The size of the one that Ramakrishna Rao now gave me fit the hand. This too, was in the Telugu alphabet. But the paper was much better than the other one; the printing was clearer as well.

Then I asked: “Is this all the work?”

R: “The second item is food.”

And so, food was savoured in a grand manner.

Me: “Next?”

R: “Now you need to come with me to the Town Hall.”

I went to the Town Hall with him. The Sita Kalyana play was being enacted there. “Gana-Kala-Visharada” (Musical Art Expert) Bidaram Krishnappa had donned Dasharatha’s role in the play. Ramakrishna Rao saod : “what – what do you say now?”

Me: “Joy to my ears, eyes and mind.”

Both Ramakrishna Rao and his accomplices sat motionless for about an hour. They wiped tears with their handkerchieves at regular intervals.

I didn’t enquire the name of the writer who wrote the script of that play. I reckoned that it was authored by a scholar with great experience. The prose, verses and songs were in elegant and graceful Kannada. The musical compositions for the songs as well as their style were apt. It’ll be a great service to those who have passion in Kannada music and literature if a manuscript of the play is unearthed and published in printed form.

On that day, in consonance with the plot of the play, when Dasharatha addresses Sri Ramachandra at a juncture, Krishnappa sang the “Mohanarama” song in the Mohana Raga. To me, it appeared that the song was the Kannada silhoutte of Tyagaraja’s compositiom, ‘Mohanarama’ in Telugu. Does music have a rule restricting it to a particular language? It’s true that the song that Krishnappa sang that day had Kannada lyrics. But his singing was beyond language; indeed, it took the form of a Divine language.

I had heard Krishnappa’s singing earlier in Bangalore - around 1910. The Sanmarga Pravartaka Sabha (literally, "Association for Promoting the Noble Path") used to celebrate Rama festival on the terrace of Sri Sahooji in Chikpet. According to my recollection, Krishnappa had sung in that assembly. His music generated a sort of excitement in Bangalore. There was only praise for his music wherever one went.

I’ve listened to Krishnappa’s concerts scores of times after that. When the Kannada Literary Festival was scheduled at Mysore we prayed to Krishnappa that his concert must exclusively feature Kannada compositions. He happily agreed.

“What’s so difficult in that? We’ll do four concerts instead of one.”

Krishnappa’s music epitomized imaginative and creative music: it was the music of one’s personal experience.

His personality was handsome. His face excluded radiance. His skin was the colour of ivory. One must say that his voice was the voice of Gandharvas-the Demigods skilled in music and dance. We don’t know how the voice of the Gandharvas sounds. We’ve only read that their voice is the best among all. But those who’ve heard his singing would say in a unified voice that the adjective "Gandharva" can only be applied in the human world to Bidaram Krishnappa.

It was said that Krishnappa’s ancestry and lineage was renowned for Yakshagana. He received training in music in Mysore. His music was marked by absolute fidelity to Shruti or pitch.

Over time, his singing fame spread all over South India. People from Madras and Thanjavur bowed to him in appreciation and honoured him.

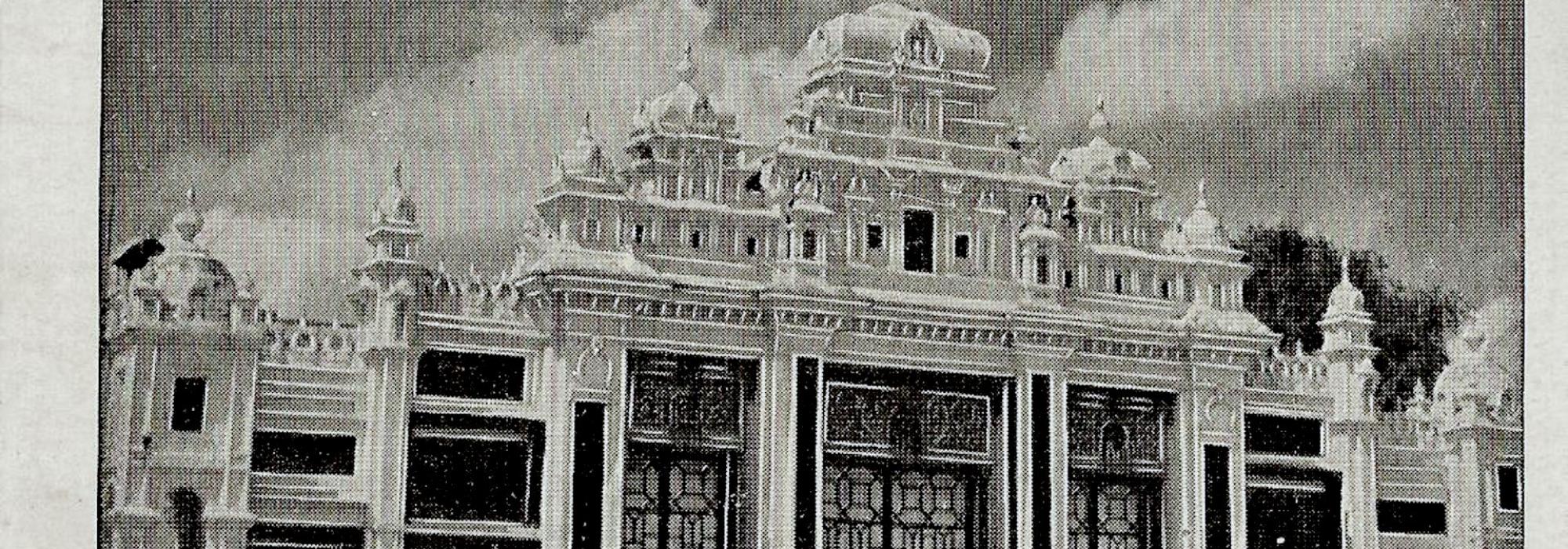

Krishnappa was a great Bhakta. The Sri Sitarama Mandira (Hall) that he established is a symbol of his Bhakti. I know a bit about the hard efforts that he put in to build it – the places he roamed to and the people he sought help from.

On one occasion during the era of the People’s Representatives Assembly in Mysore, I noticed Krishnappa visiting the resting rooms of this or the other assembly member. I asked:

Me: “Why are you taking this strain? What’s going to happen if you exert your body like this? What will be the fate of your voice be? How would you retain your creativity? Won’t it get scattered?"

K: “What else do I do? Rama has placed this task on my shoulders and is putting me through all sorts of tests. Let him. Let things turn out however he pleases.”

He said this and let out a sigh.

Krishnappa had a happy disposition. He was content with little. He had an enormous treasure in the form of his countless disciples. The most renowned among these included the “Sangita Ratna" Chowdaiah and the famous Telugu and Sanskrit scholar, Rallapalli Anantakrishna Sharma.

This is the tenth essay in D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 2) – Kalopasakaru. Translator’s notes in brackets.