Those familiar with Sanskrit–even an introductory course is sufficient–are sure to know Bhartrhari mainly via reading several shubashitas (noble sayings in verse form). Indeed, almost every other verse by Bhartrhari is a shubashita.

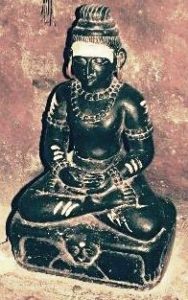

A king of Ujjain, Bhartrhari was the elder step brother of his more renowned sibling, Vikramaditya. His life presents to us a living account of a person’s transformation from a pleasure-loving emperor who had everything at his disposal to a sage who gave us the immortal Shataka trilogy.

Bhartrhari was fiercely enamored of his newly-wedded wife Pingala, a fact which caused Vikramaditya considerable anguish for the elder brother neglected his kingly duties preferring to spend his life in her arms. Pingala on her part conspired and had Vikramaditya thrown out of Ujjain.

A brahmana once gave Bhartrhari a fruit that when eaten would increase the king’s lifespan. An infatuated Bhartrhari handed the fruit to his wife. Pingala in turn, preferred the intimate company of the chief horse-keeper to whom she gave the fruit. The horse-keeper was in love with a prostitute. In the end, the fruit found itself in the prostitute’s hands. To me, the prostitute emerges as a stellar character in this whole episode. She sensed the importance of the fruit, and found it fit to give it to the king whom she believed was a wise and just ruler barring his wifely obsession of course.

Bhartrhari was counselling with his nobles when the prostitute praised the greatness of the fruit, told him she was unfit of such a lofty gift and gifted it to him. He ate the fruit and in a flash realized that it was the very fruit that he had lovingly gifted to Pingala. This singular incident made him realize the worthlessness of it all. He turned his back on worldly life and took to renunciation. The Niti Shataka has an extremely poignant verse that describes this state of Bhartrhari:

यां चिन्तयामि सततं मयि सा विरक्ता

साप्यन्यमिच्छति जनं स जनोन्यसक्तः |

अस्मत्कृते च परिशुष्यति काचिदन्या

धिक् तां च तं च मदनं च इमां च मां च ||

(The one upon whom I meditate perpetually is detached from me but

she desires another and the other desires yet another

Thus it goes always, this desire to always desire another

Fie on her, on him, on Madana (God of Love), on all this, and fie on me too!)

From King Bhartrhari, he became an ascetic, a tapasvi (the literal meaning of tapas is “to burn”) and from the ashes he burnt his passions into arose the immortal Shatakatraya: the Niti, Shringara, and Vairagya Shatakas.

The Shringara Shataka deals mainly with various facets of erotic love; it goes to great lengths to describe nuances of feminine allurement, their behavior in various stages of sensual arousal, and suchlike. Here’s a sample:

प्राङ्मा मेति मनागनागतरसं जाताभिलाषं ततः

सव्रीडं तदनु श्लथोद्यममथ प्रध्वस्तधैर्यं पुनः ।

प्रेमार्द्रम् स्पृहणीयनिर्भररहःक्रीडाप्रगल्भं ततो

निःसङ्गाङ्गविकर्षणाधिकसुखं रम्यं कुलस्त्री रतम् ||

(Noble women repulse sexual advances when dormant lies Desire

As Desire grows they loosen their limbs, shyness comes to the fore, they yawn repeatedly

Patience receding, they submit to the will of the partner, the noble women, at this critical pass,

Enjoy stroking, caressing, fondling, kissing and all other foreplay.)

The reason Bhartrhari took time and effort to pen some absolutely erotic verses has its roots in the Indian conception of aesthetics. A king himself who had enjoyed every kind of sensual pleasure, Bhartrhari took care not to trivialize any aspect of life and experience including the sensual. Indian art experience viewed as a whole is all-inclusive: nothing is shun-worthy. The end of sense-pleasure as various schools of philosophy state is self-realization, which is the end Shringara Shataka has in mind. As this verse testifies:

धन्यास्त एव तरलायतलोचनानां

तारुण्यदर्पघनपीनपयोधराणाम् |

क्षामोदरोपरिलसत्त्रिवलीलतानां

दृष्ट्वाऽकृतिं विकृतिमेति मनो न येषाम् ||

(Those alone are fortunate whose mind

Is not consumed by weakness to cast their eyes

On a pretty, young damsel; whose eyes twitter incessantly

Who is endowed with well-developed breasts and an alluring figure.)

And in the Vairagya Shataka he says there are only two ways one can live: indulge or take to asceticism. While this might seem extreme, Bhartrhari underscores the essential futility of trying simultaneously to indulge in relentless pleasure and desire eternal peace.

अग्रे गीतं सरसकवयः पार्श्वयोर्दाक्षिणात्याः

पश्चाल्लीलावलयरणितं चामरग्राहिणीनाम् ।

यद्यस्त्येवं कुरु भवरसास्वादने लंपटत्वं

नो चेच्चेतः प्रविश सहसा निर्विकल्पे समाधौ

(If there be music playing in front of you, by your side expert poets from the South,

and behind you the courtesans waving fans and shaking their bracelets with a clinking sound,

then indulge unstintingly in these worldly pleasures.

If not, O Mind, enter the realm of beatitude devoid of all thoughts.)

Bhartrhari’s trilogy encompasses almost every experience known to man and pours them forth in beautiful poetry. It provides philosophy to those interested in it, metrical delight to those who revel in it, morality to those who seek it. Everybody unfailingly gains from it depending on what they look for. Ultimately, Bhartrhari’s name stands firm to this hour owing to this. His own verse, which soulfully describes the eternity of a true artist equally apply to him:

जयन्ति ते सुकृतिन: रससिद्ध, कबीश्वरा:

नास्ति येषां यश:काये जरामरणजं भयम्

(An artist who is accomplished in aesthetic relish stands forever victorious

His body verily the embodiment of success needs no fear of old age and death.)