Any sensible mind exploring the Sundarakanda ('the beautiful section') of the Ramayana invariably feels that it has been aptly named so. Not surprisingly, there have been innumerable explanations of the explicit and implicit beauty of the Sundarakanda, all of which are very endearing. It would perhaps not be deemed superfluous, if yet another attempt is made at explicating one of the numerous beauties of this lovable episode.

Preamble

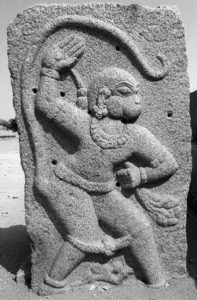

The necessary preamble to the artistic schema of the Sundarakanda is laid out elaborately in the previous section of the epic. Sugriva, the leader of the vanaras, marches off four different contingents of his army in all the four cardinal directions to find the abducted princess Sita, the loving wife of the hero, Rama. The very fact that the poet chooses to narrate the exploits of the South-bound contingent, neglecting the others, stimulates the hope and curiosity of the reader. This contingent, comprising of stalwarts like Jambavanta, Hanuman, and Angada among others, reaches the southernmost tip of the Indian mainland, only to learn that Sita is held captive on the island of Lanka, the impregnable abode of the abductor Ravana, which is a good hundred yojanas off the coast.

The task of crossing over and finding Sita is, literally and metaphorically, as immense as the infinitely expansive ocean that lies ahead. Hanuman, who curiously has to be reminded of his own latent mighty prowess, alone is capable of the colossal leap which is called for, which he indeed does accomplish.

Well-known are the obstacles which he faces on the way; clever and awe-inspiring are the feats that he achieves through his good-humored diplomacy, tact and valor; ingenious and brave is the way in which he enters Lanka by vanquishing the guardian-deity of the island-city. Let us suspend the details of these events and take a look at the flight of myriad moods that stir his bosom, as he proceeds in his endeavor.

Entering Lanka

Indeed, having assured his mates of success, he sets off with irrepressible optimism, cheer and singleness of purpose; as he enters Lanka during moonlit night, he is greeted by the alien culture of the asuras who inhabit the city. Though astounded by the luxury, sophistication and magnanimity of the city, he is steadfast in his purpose of finding Sita; naturally enough, he suspects her to be held in the harem of the villain Ravana, and for an instant mistakes Ravana’s wife Mandodari – who is asleep in her own special niche – to be Sita; with bashful self-reproach, he dismisses the thought, somehow convinced of her incorruptible moral fiber.

For one moment he is embarrassed at having entered the harem and seeing the wives of another man in various states of intoxicated compromise; the next moment he is seen consoling himself, convinced of his indifference towards the sights he has witnessed. He is restless to find Sita, but finds her nowhere; aggrieved and feeling hopeless, he suspects her to have been killed by the asuras; wavering between various states of hope and despair, he is annoyed and sad at his own failure; he cannot contemplate facing his friends on the other shore; he does not want to unleash the train of disasters that await, once he conveys the news of disappointment to his commander Sugriva, and specifically to Rama, who is already in a state of dazed devastation at having lost his dear wife; Hanuman even considers giving up his life; he considers killing Ravana and taking back the dead body with him rather than returning empty handed; a sense of dark, acute tragedy envelops his heart. As is the case with many in the face of an impending calamity, he prays to the gods for light, and discovers a vast garden that has been left unexplored.

Sighting Sita

Sifting his way through the beautiful thickets, artificial ponds, hillocks and waterfalls, and crouching upon a shimshupa tree, his eyes fall upon the object of his search – Sita, who is seated near a temple. He finds her in a state of far worse despondency than his. Though he has never seen her before, he is more or less convinced that it is Sita.

It is equally important to note Sita’s plight and her moods during this episode. She is ‘feeling humiliated’, ‘dejected’, ‘bashful’, ‘emaciated’, ‘clad in soiled clothes’, ‘teary-eyed’, ‘like a fire enveloped by smoke’, ‘sighing, like the hiss of a frightened snake’, ‘like an unfulfilled desire’, ‘like a learning, lost due to neglected practice’, and so on – yet whose charm is striking and not marred. She is constantly under the vigilance of vicious asura attendants, who keep tormenting her to accept the profane advances of the villain, Ravana.

Hanuman, adoring her tenacious, unwavering loyalty to her husband, can at the moment only watch her silently. At dawn, Ravana appears, heaping copious praises on her beauty and courting her love; Sita, refusing even to cast a direct glance at him, spurns him and warns him of the invincible wrath of her husband and, vainly, tries to dissuade him from his perilous folly. Ravana, who is cursed with death if he forces himself upon any woman, grants her two months’ time to accede to his proposal, failing which she would be ‘consumed as breakfast’, and retires to his palace. Lamenting and powerless, unable to bear the slovenly persuasions of the wicked attendants, Sita contemplates death. One of the attendants, a lady of kind disposition, tries to console Sita by describing her ominous dream the previous night, which portends Ravana’s death. This is of little solace to Sita; her state is not unlike Hanuman’s, who was swaying between hope and despair. She approaches the very tree upon which Hanuman is hiding, in an attempt to hang herself from its branch with her own long braid, when a series of ‘auspicious omens’ occur, imparting a sense of hope to her – though, how well, and for how long, it could have comforted her is anybody’s guess.

The poet, who had begun the portrayal of the Sundarakanda with the color of a probable hope, at this point, has painted the picture of a bleak emotional impasse. The reader cannot escape the gloomy, sinister mood that hangs over these events. How this poignant deadlock is broken, and the potential cause behind it, is of significant beauty.

The Meeting

Hanuman, perched upon the tree, witnesses the events below and is at loss as to how he should pick up a conversation with Sita, without petrifying her any further and without alarming the guarding attendants. He cleverly begins by singing, in a low voice, the tale of her husband Rama, of her own marriage, her abduction by Ravana, and finally, the later events which have brought him to Lanka in search of her – of which she is unaware. Dismayed, Sita sees Hanuman and considers the whole episode to be a hallucination of her own intense desires; however, she earnestly prays that it be true. Even a hallucination in moments of deep distress can be very soothing! Hanuman wanting to confirm her identity, questions her about the same, and she replies to this ‘welcome hallucination’ by relating her own story completely. She is overcome with joy by this unexpected turn of events. Yet, it is but natural that she doubts him several times again, considering him to be Ravana (who can change his appearance at will) playing some other devious trick, and questions him several times about Rama, her husband; Hanuman in turn convinces her by repeatedly describing the persona of Rama, in words of deep reverence.

The chief aim of this essay is to consider a verse which occurs at the beginning of this process of repeated reaffirmation. This verse, though very simple, is imperative, because it marks the ‘beginning of the end’ of the emotional impasse that was spoken of above, and it also conveys the cause of the same; more importantly, the import of this verse has a subtle, causal bearing on the word ‘sundara’ (beautiful), in the name given to this section of the epic. The poet has very touchingly and powerfully captured the ‘mood swing’ in this verse. It runs thus:

तया समागते तस्मिन्प्रीतिरुत्पादिताद्भुता ।

परस्परेण चालापं विश्वस्तौ तौ प्रचक्रतुः ॥

She (Sita) developed a wonderful affection towards him (Hanuman), who had arrived (to meet her). With implicit mutual trust, they started conversing with each other. (Sundarakanda 34.7)

So we see that it is trust, 'vishvasa'. A trust which is mutual, has resolved the impasse. It is trust that is causing the torrential flow of words and emotions between them. It is trust that has unburdened the heart.

Whence this unprecedented confidence in each other? Is Sita’s trust in Hanuman merely incidental? Is it an opportunistic, temporal bargain that has ensued in the face of a sheer, helpless crisis? Of course, as final proof, Hanuman offers a ring which carries the personal seal of her husband Rama. Has the beautiful trust that has just been formed, dependent solely on such a tangible object?

No. It is seen that when Sita suspects Hanuman to be Ravana in disguise, she doubts her own suspicion, saying:

अथवा नैतदेवं हि यन्मया परिशन्कितम् |

मनसो हि मम प्रीतिरुत्पन्ना तव दर्शनात् ||

No! What I doubt cannot be true, for a certain fondness has been involuntarily generated in my heart by seeing you! (Sundarakanda 34.17)

What has caused this beautiful, intuitive bonding?

Trust

There is a natural, latent fear and inhibition that exists in all beings; it is these that determine and define individuality of a being; it is these that keep an individual, an individual. In animals this exclusivity can go absent due to many natural reasons. In humans, this exclusivity is instinctively discarded when there is a meeting of like minds – minds of a mutually agreeable, deeply ingrained culture and character. There can be nothing more beautiful than the melting away of this exclusivity which results in an undeterred, blissful, exchange of thoughts and emotions. This dispelling of exclusivity, indeed, is trust. Upon close observation, we can find that it is only such a trust, in varying degrees, that really makes life beautiful and renders all empirical transactions possible. What has occurred in the case of Sita and Hanuman is verily this. Even if their mutual acquaintance had taken place under a different, happy circumstance, it would never have failed to produce the selfsame trust, love and respect for each other. That this trust has come into being in a period of distress, only adds to the beauty and value of it.

It is worthy to recall here that, earlier in Ramayana, a similar trust had been developed almost instantly between Rama and Hanuman. The personality of Rama so deeply affects Hanuman that, later when he is discovered by Ravana, he boldly declares him to be a mere servant of Rama! Rama too, speaks very adoringly of him. Hanuman, it seems, is a very able judge of men’s character, and not only that, he also chooses to be with the people whom he considers virtuous. Much earlier, when Sugriva, the king of the vanaras, is mercilessly exiled by his brother Vali, Hanuman, seeing some serious flaw in Vali, takes the side of Sugriva.

To revert back to Sita and Hanuman: What is the character and culture of these two individuals that has at once, forged this trust?

The poet has portrayed them powerfully by bringing in two stark contrasts in this very episode: One, that of Ravana and Hanuman; the other that of the occupants of the harem and Sita. Hanuman, through his guileless, honest, humble and respectful behavior has produced in Sita, an effect that is exactly the opposite of Ravana’s. Sita, by her stern rejection of Ravana and the many luxuries that he could have offered, has produced an effect in Hanuman, which is opposite to the one that had been caused in him by witnessing innumerable women of the harem, who have acceded to Ravana either by trick or coercion. The extent of trust that has been generated in Sita is evident from the fact that, overcoming her natural feminine bashfulness, she reveals an intimate, romantic episode that had taken place between her and Rama; she asks Hanuman to recount this episode to Rama so that he believes the fact that she has been successfully traced out; for the same reason, she also hands over to him a crest-jewel of hers.

Aftermath

Much of what follows is beyond the purview of the proper context of this essay, though a brief outline is necessary to complete the narrative. Hanuman is capable of carrying Sita back to Kishkinda, where Rāma currently camps with his brother. She refuses this offer for reasons best known to her. She offers some reasons for doing so. Additionally, one can imagine that perhaps she thinks sneaking away would not be a befitting redressal of the humiliation she has suffered; perhaps she wants her own hero to come to her rescue; perhaps she wants to teach Ravana a lesson in straightforward behavior, and thinks that merely vanishing from the scene is imitating Ravana’s shameful cowardice.

Hanuman, later in a fit of fury, destroys the garden in which Sita has been held. He is discovered by the asura army; he fights and kills many of them; he is finally held captive and taken to the court of Ravana. His tail is set on fire, using which he burns down a good portion of Lanka. Escaping and crossing over to other shore, he joins his friends and they triumphantly march to Kishkinda, reveling on the way. Hanuman conveys to Rama, the fact that Sita has been spotted and also tells him her message, handing over her crest-jewel.

Rama overwhelmed with gratitude, embraces him in love and honor. But this final detail has been carried over to the opening chapter of the next section, the Yuddhakanda ('the war section'). By doing this, perhaps the poet wants to convey that the same trust that Hanuman enjoys with Sita, is once again relived in Rama, and that this trust, as it has instilled faith in Sita, has also revived faith in Rama, who is now ready to take on Ravana in the massive war that is to follow.

Conclusion

True, the Sundarakanda has many more beauties to its credit. There are elements of a mystery story in it, which has mass appeal; there is the description of the ocean, the city of Lanka and the Ashokavana in which Sita is captive; there are vivid descriptions of the personalities of Rama, Sita, Hanuman and Ravana, and many more such literary feats of beauty, which pour out with profound aesthetic ability from the natural genius of the immortal poet, Valmiki. There is of course the wonderful reunion of the hearts of separated lovers, yearning for each other; one of the most sublime of them all, is the depiction of the beauty of trust, which resuscitates faith – another facet of trust – in them, and thus becomes the cause of the dispelling of fear and sorrow from their hearts.

All great literary works, especially epics like the Ramayana, are always seen in two different contexts. Firstly they are considered purely in the context of ethical values they promulgate, which has a direct bearing on the lives, moral principles and culture of a civilization at large. Secondly, they are considered purely in the context of artistic values, what is more popularly known as literary criticism.

In the first context, there is no doubt that a fundamental truth has been represented: in actual life, beauty can reign only in the absence of fear and sorrow, and their absence necessarily implies the presence of trust and faith. The stand point of the poet, which throughout the ages has been the core of Indian ethical system, is amply clear. Anyone who is in the habit perpetuating fear and sorrow is morally wrong, and those who fight such a person and his actions, are moral. All those who adhere to this will naturally appreciate the aspect of beauty that has been explained above.

The second context of pure literary appreciation (criticism) looks at the sheer, aesthetic efficacy in depicting the characters, emotions and events – suspending the ethical question. It looks upon both good and evil characters with an equal eye, considering only the potency of literary expressions in generating the intended human emotions in the readers, without blowing them off their feet. This context, however, cannot escape the responsibility of being true and honest to the fundamental, intrinsic reality (nature) of human emotions. The liberty of a poet is only in representation; that is, the liberty is only to the extent of choosing, amplifying and contrasting these fundamental emotions. As seen above, this has been realized to the fullest extent in the artistic portrayal of the characters and emotions involved.

Thus, both humanistic and literary beauty of this episode enraptures the readers, and leaves an everlasting impression in them.

Author: Raghunandan