In this survey of history, l have touched all the frontiers I had intended to. It is a wheel of time spanning sixty years between 1880 and 1940.* The historical events after 1940 is not relevant to my present purpose.

After Mirza saheb, the person who assumed power as the Dewan was Pradhāna Śiromaṇi Sir Nyapathi Madhava Rau. After him, Dewan Bahadur Sir Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar took charge. With his tenure, the position of ‘Dewan’ came to an end. Mudaliar came in as the Dewan, and later went on to become the first Chief Minister of the Responsible Government before retiring. During his administration, Śrīmān Kyasamballi Chengalaraya Reddy had worked as his colleague for a few months. Thereafter, Reddy himself became the Chief Minister during the rule of the Responsible Government. Everybody knows the people who became the Chief Ministers after him. I believe I don't have enough authority to talk about them. I am ancient, they are modern. If I am told that my mind is prejudiced, I cannot deny it. It might be a fact. I lack the courage to claim that I am the purest and that my mind is the most uncontaminated.

In the year 1940, my contact with public organizations such as the Legislative Assembly came to an end. Thereafter, there was no direct communication between me and the government. Since then, I have been merely a witness – a witness from afar.

Nyapathi Madhava Rau

It will be untruthful to say that I did not know Śrīmān Nyapathi Madhava Rau. Since his tenure as the Secretary of the Government, I had closely observed his method of working; I had also earned his affection. If anyone feels that my opinion about him is biased, it is not possible for me to prevent that. However, hiding my opinion fearing what people will say is not the manner in which truth should be upheld. My earnest opinion about Nyapathi Madhava Rau is that he was venerable in all aspects.

Rau was a brilliant thinker with all-round awareness and a man of integrity. He was a person who had earned his position of authority purely based on his intellectual capabilities. He worked in different regions of the State, and through experience he learnt about the challenges and testing situations that lay in front of the government. He immersed himself into the lives of the common people, and understood their character and behavioural traits; he was a man with genuine empathy.

In this manner, although his nature won the affection of the people, it wasn’t the sort of affection bereft of culturing. Madhava Rau had studied law in depth with a keen eye. He was a legal expert who had critically examined and understood the nuance of the discipline of law – be it the expanse of jurisprudence, interpretation of legal terminologies, and the fundamental principles of its regulations. I have felt many a time that if he had chosen the judicial department over administration, he would have gone on to become a renowned judge. His knowledge of law was that sharp and well-rounded. He had been recognized as a talented individual even as a student. Around 1907, he cleared his Mysore Civil Service Examination securing the highest rank in the Princely State and started his career as a Probationary Assistant Commissioner. In 1909, in addition to graduating with a BL degree from the Madras University with a first rank, he secured many awards and medals like the Carmichael Prize.

Nyapathi Madhava Rau worked in various departments of the Mysore Government and the Mysore Municipal Corporation; as the Chief of many organizations such as the factory at Bhadravati [Iron and Steel Plant]; and in several high positions such as Revenue Commissioner, Muzarai Commissioner, and Trade Commissioner of Mysore in London. He presided over several government organizations such as the Mysore Representative Assembly, the Legislative Council, and Bangalore Urban Development Authority and served as the member of the Constituent Assembly as well as foreign delegations constituted by the Government of India. In all these capacities, Madhava Rau earned repute for his competence and long-term vision.

Madhava Rau was a man of few words. He would speak only as much as he felt was sensible and necessary; his speech would neither be too less nor too much. It was his nature to speak cautiously and weigh his words while talking.

Downfall of the Public Decorum

Although Madhava Rau’s legal acumen and his love for people had been widely embraced by everyone, the social environment was not very conducive for him. Even during the tenure of his predecessor Mirza Ismail, public decorum and dignity of office had slackened while mob furore had started. During Madhava Rau’s tenure, the age-old practices of public decorum degraded further. I vividly remember – one evening, he asked me for my suggestion. It was around the time when a British minister by name Cripps (Sir Stafford Cripps) was slated to visit India. When Sir Cripps visited India to deliberate upon the political affairs of the country, K T Bhashyam indicated to me to be a part of a delegation that required a few people with the citizens’ perspective to discuss the future of the Princely States with him [Cripps]. However, I communicated to Bhashyam that I was not qualified to take on the responsibility since I was not representing any public organization. Instead, given that Bhashyam was a Congress leader, I pointed out that he was competent to take up the task himself. I suggested to him that he could propose this idea to Dewan Madhava Rau. Accordingly, when Bhashyam spoke to Madhava Rau (over telephone), the Dewan apparently expressed his desire to meet me. Subsequently, when I called upon him, the first question he asked me was this: “How do we make our people follow the Assembly’s decorum?”

I replied, “Sir, it appears that the time to teach decorum has passed. Our people had inherited the practice of reverence and dignity as a saṃskāra [sacrament, self-refinement] for thousands of years. Due to this saṃskāra, our people had developed respect for the government quite naturally. People respected government authorities for a certain set of reasons. The first reason was decorum. The second was their adherence to truth. The third was their scholarship. The people who assumed authority earlier were well known for their conduct, integrity, education, and intelligence. Due to those traits, people willingly revered them. Now, that treasure-trove of qualities has turned deficient. You are well aware yourself as to the kinds of people who have gained power in the State. Fearing such powerful people, if the government starts promoting them indiscriminately, how will the citizens—who know their real worth—show respect to them? This is the situation today. Realizing the fact that there is no choice but to take shelter under random unworthy individuals, the people merely show as much respect to them as is necessary, in a superficial manner. These days, the work of the government has become particularly difficult!”

To be continued...

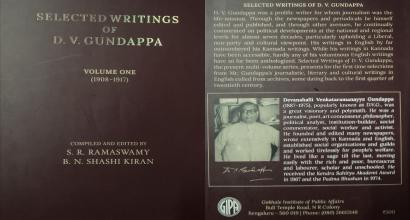

This is the first part of an English translation of the thirteenth chapter of D V Gundappa’s Jnapakachitrashaale – Vol. 4 – Mysurina Diwanaru. Edited by Hari Ravikumar.

* The period of ‘sixty years’ is significant since it is the period of the traditional saṃvatsara-cakra (sixty-year time cycle) of India.