It appears that the God Brahma who was so munificent in bestowing the boon of command over language to Venkatarama Shastri indulged in mischief in the matter of giving him speech. If this wasn’t true, what explains the fact that a Vidwan—an accomplished scholar—like him stammered at every step? It was for this reason that all the village folk referred to him as “Stammering Shastri.” This appellation was merely for the convenience of identification, not ridicule. Everyone had reverence-filled affection and respect for Shastri.

The assets that Shastri possessed included just these: an earthen roof-house, a small field, and some palm-leaf books. He had two sons. The elder one was a doctor and had learnt violin. The younger one was the son-in-law of an affluent family and lived pretty much in his wife’s home. His daughter lived with her husband in a different town. Shastri had relegated familial worries to his wife and children and lived like a guest in his own home.

Method of Teaching

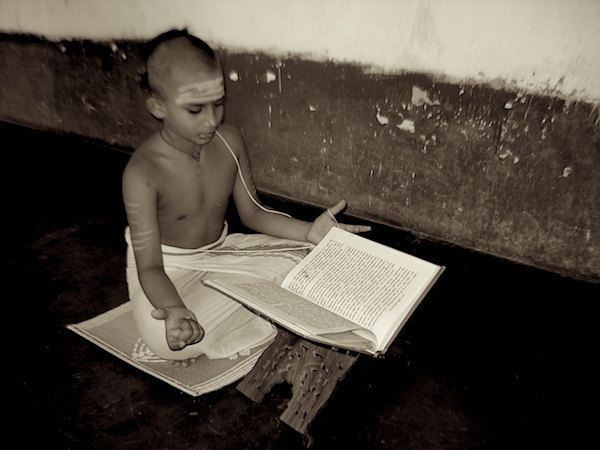

Although his mother tongue was Kannada, he was renowned as a great Pandit of both Sanskrit and Telugu. At any point, there’d be about four or five students learning Sanskrit from him (in the Gurukula system, where pupils lived with the teacher in his house). Typically, Shastri would awake at about four or four thirty in the morning, and poke one of the sleeping students with his stick, and then indicate the awakened student to wake the others up. Shastri always carried the stick with him. He kept it next to him even as he slept. When he had to say something, he’d poke the intended person with it and draw the person’s attention towards him.

Thus woken up by the stick-poking, the students would wash their face and sit in the glow of a small lamp fed with beech oil. Then one of the students would open the book and read the lesson for the day. It would be Raghuvamsham or Shishupalavadha or Uttararamacharita—Shastri had no need for a book. He had assimilated the book. While reading, if the student made an error in either the alphabet or word-division, Shastri would prod him with his stick. The student would understand on his own that he had made a mistake, would correct it and re-read it. Or his classmates would suggest the correction. Normally, the prodding would continue relentlessly until the student learned how to read correctly without making a single error.

It was only when Shastri himself realized that it was impossible or difficult for the students’ abilities to grasp a certain portion that he would open his mouth. It was extremely tough for him to utter the initial words. After that, they flowed out generously. It was because he had this inborn speech-impediment that majority of his teaching had to occur via that stick. Word-division, meaning, compound-words, word-order, syntax—the students had to put in their own effort to master all of these. Indeed, it was Shastri’s conviction that it was good that learning took place in this manner. Perchance even if he didn’t have the stammering impairment, it appears that he’d still follow the same method of instruction.

Teachers of yore weren’t afflicted with the madness of the new method which wants to make the job of the students easy. The student has to labour hard on his own; his fruit was proportional to his effort—this was the philosophical attitude of the ancients.

Knowledge is something that resides within the student. The only task of the teacher is to move the walls that enclose and block its light. If he does just this, the light of the lamp therein will spread out on its own. Knowledge is not something to be shoved in from the outside; it’s to be called out from within. This is the work of the teacher. It’s because Venkatarama Shastri adhered to this precept that the learning of his disciples in literature and grammar was spotless and accurate.

Shastri composed poetry as well. He had composed hymns (stotra) and kirtans for his own joy and (spiritual) inquiry. He authored the PUrvadwArapurI mAhAtmyamu” in the Champu style in Telugu. It contained majestic prose, metres of various classes, verses in the Kanda and the SIsa style, and Padams designed for Kolata or stick-dancing. He had entrusted the task of making a fair copy of this work to my friend Vyasaraya and me. I had to read it aloud to him and he had to write it down. Vyasaraya wrote in elegant, pearl-like alphabets in shiny blue ink on milky white paper. This was some fifty-three years ago. Nobody knows where the book is. It doesn’t appear that my quest for it yielded any fruit.

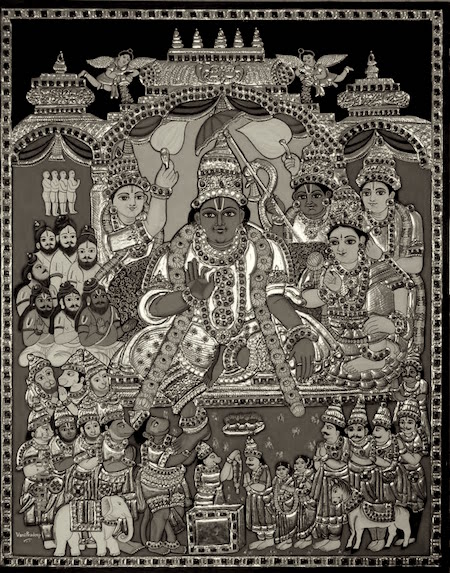

An Ardent Devotee of Sri Rama

Shastri was an ardent devotee of Sri Rama. In this Chaitra month of every year, he organized the Sri Rama Festival and on the day of Rama’s Coronation, he held a feast for about a thousand people. For the purpose of the feast, he’d visit different villages throughout the year and collect the requisite supplies. He’d take along with him a gunny bag wherever he went. He’d put in it whatever anybody offered, uttering “Sri Ramarpana” (This offering is for Sri Rama), and return to the Mantapa near the Someshwara Temple.

Nobody refused Shastri. Folks would give rice, pulses, wheat flour, jaggery and other provisions according to their ability. Others gave firewood and vegetables. Still others offered plantain leaves and packets of bowls (made of dried leaf). Some gave commodities. Folks also offered two or three mounds of jaggery or two pails of paddy. Some people also put ten coconuts in a bag, which was securely knotted and on which was written, “For Shastri—Offered to Sri Rama” and waited for him with an additional offering of half an Anna (fifty paise). Shastri stored the supplies thus collected in the Mantapa near the Someshwara Temple.

On the day of the feast, more than a thousand people including women and children would assemble. Cooks wouldn’t take their normal fees and be content with whatever Shastri gave them. Several among those who came to eat also assumed the errand of serving food. It would take three or four rounds to serve the entire crowd. The feast would be quite grand including sweet delicacies like Holige and Kheer (pAyasa), and lemon rice. Shastri would visit each line of guests and speak a few words of hospitality, making them feel honoured.

After food, he would pray to them to accept the Tamboola (a mixture of betel leaf, areca nuts, lime and other ingredients typically chewed after a meal as a digestive aid) outside temple. He gave a Dakshina or gift, of half an Anna each to the adults, and a quarter Anna each to children along with the Tamboola.

This done, he would bring out whatever was remaining in his storehouse and then:

“One ball of jaggery is remaining. Anybody may take it,” he’d call out.

He’d give it to whichever raised hand that his eyes spotted first, together with a quarter Anna and utter, “Sri Ramarpana.”

“Here’s an old umbrella. Its stick is broken. If it’s fixed, it’ll be of use. Anybody…”

He’d then place it in the palm of the one who wanted it and say, “Sri Ramarpana.”

“Half a packet of leaf-bowls is remaining. Ten or twelve of them, maybe. If anyone wants…”

Again, “Sri Ramarpana.”

“This is a footwear. Collected from someone in Madipalli. It’s a little torn. If mended, it’ll come of use…”

As above, “Sri Ramarpana.”

“Ten cowpats remain. Those who want…”

“Sri Ramarpana” as usual.

In this manner, Shastri would wash his hands off by distributing all material possessions including money.

During one of these annual feasts, Shastri’s wife Parvatamma broke a small piece off a jaggery mound in the storeroom and gave it to her grandchild. Shastri saw this and complained, “What’s this? Can we take something obtained by begging for the specific purpose of offering it to Sri Rama, for our personal use?”

She asked, “You’ve never committed the sin of placing a single Paisa in your children’s hands. Neither have you given even a scrap of food to them. What did you lose if I give my children a bit from what others have given you? Aren’t children akin to God?”

Shastri questioned, “So, are only your grandchildren akin to God?” Then he bunched together some ten or fifteen children present there, and asked, “aren’t these akin to God?”

Now, the old couple exchanged heated words. In the end, Shastri declared, “Your tongue has become abrasive of late. I don’t need you to cook for or take care of me from now on.”

And so, Shastri began to cook for himself from that day onward.

An Unknown and Obscure Life

He would teach from five in the morning up to eight or nine. Then he would go to the lake, wash his clothes, bathe, wear fresh, sacred clothes, finish his Sandhyavandanam and other daily duties, and then go to the Anjaneya Temple. There, he’d sit in an appointed place and chant from the Srimad Ramayana till about twelve. Those who saw him chanting refused to believe that he had a stammering impairment. Verses would cascade out of his mouth in an unbroken stream.

By then, the Vaishyas (businesspeople) and other devotees who came to the temple would approach him, bow to him and offer say, a slice of pumpkin, coconut, two bananas, or four guavas—basically whatever their abilities allowed them to.

Shastri took these home and gave away what he didn’t need and retained say, a pumpkin slice, some copra; or a couple of bananas, a slice of coconut, some jaggery. Typically, he boiled the pumpkin and prepared curry, ate it, and drank buttermilk. Because he knew some Ayurveda, he had prepared a (health) powder of sorts and mixed it with the pumpkin curry. This was all of his food. Only once in twenty-four hours.

By now it would be three in the afternoon at which time he would go to the temple priest, “Archaka” Krishnappa’s house.

Now aged and retired, Archaka Krishnappa had been the priest of the Anjaneya Temple. He too had attained great scholarship in Sanskrit, Telugu, and the Agama Shastras (broadly, the branch of knowledge dealing with rules regarding the conduct of rituals in and construction and management of temples). His son, Shama Dasa had studied (Sanskrit) literature under Shastri and had earned renown in Harikatha and the Puranas.

There was a stone bench in front of Krishnappa’s house. Because the house faced east, shade fell on the stone bench and rendered it cool and soothing. Krishnappa and Shastri would sit next to each other on it. Two nutmeg boxes before each. Both boxes were filled with balls of dry clay the size of a large tablet. Maybe a thousand of them.

Both Krishnappa and Shastri would extract one tablet at a time and then uttering, “Om Sri Ramaya Namah,” would drop it in the empty box. After it was full, they would again pick up one tablet from it and again utter “Om Sri Ramaya Namah” and drop it into the first box. In this manner, the tablets would change boxes for about five, six or ten times each day. The idea was that they had chanted the Sri Rama Mantra for that many thousand times.

Amidst this chanting, if someone passing by spoke to them, there was a bit of conversation, exchange of pleasantries, and spiritual discourse. At times, just the two of them would select a Shloka or a line or phrase from the Vedas or a situation from the Puranas and launch into a learned disquisition on it. Thus, the chanting also involved discussions about the welfare of the world, philosophical inquiry, and nuances of aesthetic appreciation of literature.

Both Shastri and Krishnappa lived in this manner till the end. In about two or three years after Shastri began cooking for himself, his wife passed away. Shastri lived for about ten or twelve years after that. As in the past, he lived a life of self-reliance, expecting nothing from anyone, adhering to the traditional rules of piety and principle. He didn’t earn money, didn’t build a house, wasn’t decorated with shawls, didn’t carry awards, desired nothing. He didn’t feel the need for anything. He was content with his crumbling house and his tattered dhoti.

It was an uncelebrated, unknown and obscure life. Is there anybody in today’s world who desire such uncelebrated contentment? Indeed, for today’s people, Shastri’s life-history will sound like a tale of arid madness.

This is the thirteenth essay in D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 1) – Sahiti Sajjana Sarvajanikaru. Translator’s notes in brackets.