Adhyāyas 4-12. Pauloma-parva

The adhyāyas from 4 to 12 form the Pauloma-parva. Just like the anukramaṇikā (prologue), this section starts with a prose passage.

रोमहर्षणपुत्र उग्रश्रवाः सूतः पौराणिको नैमिषारण्ये शौनकस्य कुलपतेर्द्वादशवार्षिके सत्रे |

(Sūta-paurāṇika Ugraśrava, the son of Romaharṣaṇa during the twelve year long satra conducted by Śaunaka in the Naimiṣāraṇya,....)

This is followed by a few more lines of prose and verses. When Ugraśrava, the Sūta-paurāṇika, asks them which story they would like to hear, they replied, “Our kulapati Śaunaka is now in the agni- gṛha (the place where the three sacred fires i.e., gārhapatya, āhavanīya and dakṣiṇa are housed). Let him come and we shall consult him. You may kindly narrate the story that he wishes to hear.” Upon the completion of his work, Śaunaka joined them and told Ugraśrava that he wished to listen to the stories of his ancestors. Śaunaka belonged to the Bhṛgu-vaṃśa (lineage of seer Bhṛgu) and so the Sūta-Paurāṇika starts narrating the stories of that lineage. Starting from the seer Bhṛgu, he narrated the story of Bhṛgu’s son Cyavana, his son Pramati, his son Ruru, and Śunaka, who was Ruru’s son. How did the name Cyavana arise? The next two adhyāyas are dedicated to answering this question. A rākṣasa by name Puloma harassed Pulomā, Bhṛgu’s pregnant wife and her foetus was ‘cyuta’ (separated, fell) from her womb and hence the name ‘Cyavana.’ (Since this segment mainly deals with the story of Puloma and Pulomā, it is called the Pauloma-parva.) Later, Ruru marries Pramadvarā. (Just like Śakuntalā, Pramadvarā too was a daughter of Menakā; she was born through a gandharva named Viśavasu. Menakā abandoned the infant on the banks of a river, where the seer Sthūlakeśa found her; he raised her as his own child.) Pramadvarā dies of a snake-bite and Ruru rejuvenates her by offering half of his own life-years. Because of this, he develops animosity towards all snakes and kills every snake that caught his eye.

Once, when Ruru had raised his hand to kill a water-snake by name Ḍuṇḍubha, the snake said, “I’m not a poisonous snake. Non-poisonous snakes are not dangerous. Further, I’ve turned into a snake due to a curse. Now I am released from the curse, thanks to you. A brāhmaṇa should not harm animals. To punish is a kṣatriya’s job. In the past, when Janamejaya was performing the sarpa-yāga, a brāhmaṇa named Āstīka stopped it. (This portion of the story is yet to take place in the sequence of events. Also, this Janamejaya is a different one and belongs to the previous kalpa. The commentators’ explanation for this is merely that all these events have a cyclic repetition and had also taken place in previous kalpas. It is also possible that different recensions of the Upakramaṇikā portion have got mixed up and this inconsistency in the sequence of events has crept in.) Ruru asks Ḍuṇḍubha, “How did the kṣatriya Janamejaya punish the snakes? Why did he do so? And why did Āstīka come to their rescue?” The seer who had been freed from the curse told Ruru, “Āstīka ’s is a long story. Ask any brāhmaṇa and he will tell you!” Saying so, Ḍuṇḍubha vanished. Ruru learns of this story from his father Pramati.

Adhyāya 13-53. Āstīka-parva

Āstīka (upa-) parva ranges from the thirteenth to the fifty-third adhyāya. This is ancient history narrated by Kṛṣṇa-dvaipāyana. Ugraśrava’s father Lomaharṣa (also called Romaharṣaṇa) also narrated this to the brāhmaṇas. The Sūta-paurāṇika Ugraśrava, upon hearing this story from his father, retells it to Śaunaka and other sages (Adhyāya 13, verses 6-8). The main story of this segment is as follows:

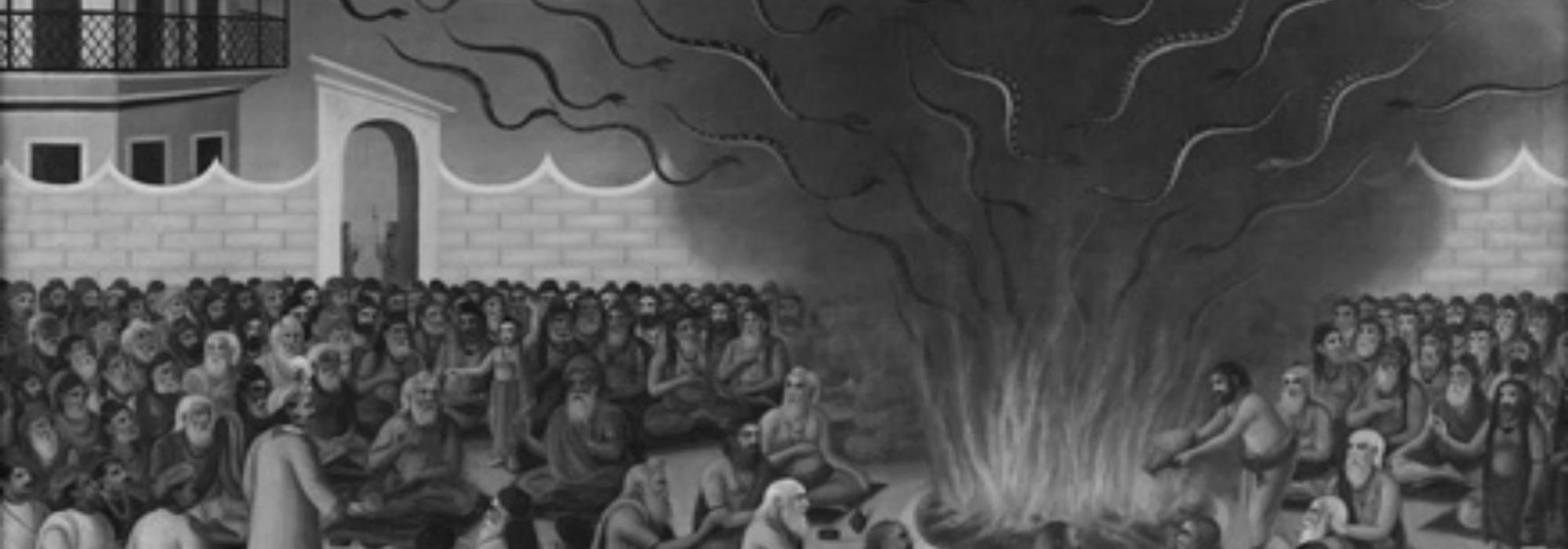

The king Parikṣit who has gone hunting encounters a seer in silent meditation, whom he interrogates regarding the whereabouts of the deer that he had just shot. The seer remains mute. The enraged king, with mischievous intent, garlands the seer with a dead snake. Śṛṅgi, the son of seer Śamīka, who happens to come there, notices this prank and curses King Parikṣit to die of a snake-bite. The curse finds its fulfillment in Parikṣit’s death due to a snake-bite. To avenge his father’s death, Janamejaya vows to eliminate the entire serpentine species and undertakes the sarpa-yāga. While the yāga was in progress, Āstīka—the son of the serpent-king Vāsuki’s sister—comes to Janamejaya, praises him and his undertaking of the yāga, gains his confidence, and requests him to stop the yāga. King Janamejaya, who was well-versed in dharma, knew that it was only correct to fulfill the wish of a brāhmaṇa while a yāga was in progress; accordingly he acquiesces to Āstīka’s request and stops the sarpa-yāga. Delighted, Āstīka goes away.

When the sarpa-yāga was going on, during the breaks, Vaiśampāyana narrated the story of the Bhāratas. This has become a great epic since the story constantly branches out in various directions but eventually keeps finding its way back to the root-story.

Āstīka’s father Jaratkāru was once immersed in tapas and had given up thoughts about marriage. His ancestors, the Yāyāva sages, were deeply saddened since Jaratkāru’s celibacy would put an end to their lineage. In order to pay tributes to the ancestors, Jaratkāru made up his mind to get married. [Progeny was seen as imperative for the sustenance of the lineage and also to honour the dead ancestors.] But he wanted a wife who would listen to his words and her name was to be the same as his. Although he was poor, he expected that the bride’s family would come of their own accord and offer their daughter in marriage. Fortunately, the serpent-king Vāsuki had a sister who fulfilled the criteria. He gave his sister’s hand in marriage to Jaratkāru. However, his family life was short-lived. Frustrated and upset with her, he abandoned her even as she was pregnant. Later, Āstīka was born to her and grew up in his uncle Vāsuki’s house.

The reason for the death of so many snakes in the fire of the sarpa-yāga was due to the curse of Kadru, the mother of all serpents. What is the reason for this curse? To know the answer, we have to rewind to the beginning of creation. The creator Prajāpati had two daughters, Kadru and Vinatā. He got them both married off to Kaśyapa . The snakes were born to Kadru; Aruṇa and Garuḍa were born to Vinatā. Once Kadru and Vinatā had an argument regarding the colour of the divine horse Uccaiśravas – whether it was black or white. It was agreed that the loser would become a slave to the winner. Vinatā said that the horse was white in colour while Kadru said that its tail was black. Indeed, Uccaiśravas had a white tail and Vinatā should have justly won the argument. However, Kadru, fearing slavery to Vinatā, ordered her children to stick on to the horse’s tail and make it appear black in colour. But they refused to abet this crime. Furious, Kadru cursed them: “All of you will get reduced to ashes in the sarpa-yāga that Janamejaya will perform!” A few serpents, having gotten afraid of the curse, stuck to the tail of the horse, making it appear black. This made Vinatā and her son Garuḍa the slaves of Kadru. Garuḍa fought the devas and brought amṛta (elixir of immortality) to the nāgas, thus freeing himself and his mother from slavery. Indra, however, hoodwinked the serpents and took the amṛta away before they could partake of it. All that they could get in the end was slit tongues, having licked the blades of the darbha grass on which the pot of amṛta had been placed.

At the mention of amṛta, the story switches to the samudra-mathana episode (churning of the milk-ocean for amṛta). The narration starts with the churning of the ocean, the appearance of poison and several other items, and finally the emergence of amṛta [soma is also used synonymously with amṛta; adhyāya 30, verses 7, 8, 13, 18, and 19.] Viṣṇu, in the guise of Mohinī, distributes the amṛta only to the devas. This and several other stories with all their vivid details appear in this section.

We have already seen that Śṛṅgi, the son of Śamīka, cursed Parikṣit. However, Śamīka did not approve of his son’s act. “Parikṣit is, after all, a king. Moreover, śama (self-control) and kṣama (forbearance) are the ornaments for a brāhmaṇa . Thus I shall inform him of this. Let him plan for his safety!” Saying so, he asked his student Gauramukha to inform Parikṣit of the curse. According to the curse, Parikṣit was to die within seven days of Takṣaka ’s bite. Thus, Parikṣit retired to an enclosure with a single pillar supporting it and had tight security arrangements made. He had with him physicians and māntrikas (people highly accomplished in mantra-lore). He executed his kingly duties from this enclosure. Six days passed.

On the seventh day, a māntrika by name Kaśyapa , having heard this news was on his way to Hastināpura, claiming that he could cure Parikṣit of a snake-bite; he was driven by an ulterior motive of making money. Takṣaka, who happened to be on the same path, met Kaśyapa and asked him who he was and what he was doing. After learning about Kaśyapa’s intention, Takṣaka decided to test his skills in mantra-lore. So he bit a banyan tree that was nearby, which instantly turned to ashes. Kaśyapa , with the power of his mantras, revived the tree. If such a skilled māntrika were to be around, Takṣaka feared that his mission would not succeed and therefore paid large sums of money to Kaśyapa and sent him away from there. Having received the money, Kaśyapa thought to himself that it was anyway time for Parikṣit to die and went back the way he came. Takṣaka reached the enclosure and realized that the place was heavily guarded. He called a few of his snakes and ordered them to put on the guise of sages and visit Parikṣit with fruits and flowers. Since they appeared as sages, no one prevented their entry into the enclosure. The king received the sages cordially and accepted their gifts of fruits and flowers. He distributed them to his aides and also picked up a fruit to eat. Inside that fruit, Takṣaka had hidden himself in the form of a worm. Parikṣit picked up the red worm with black eyes and told his ministers mockingly, “The sun is setting. I don’t think I have to fear poison anymore. If this worm bites me in the name of Takṣaka , let it do so! Let the words of the sage come true! We shall find a remedy for it!” Saying so, he picked up the worm and put it on his neck. The worm turned into Takṣaka , coiled itself around his body, and bit him. He succumbed to the poison-rage. The enclosure too was reduced to ashes along with his people.

The ministers organized his last rites and crowned the infant Janamejaya as the king. After he grew up, once Uttaṅka came to him and instigated him to conduct a sarpa-yāga (as narrated earlier). Janamejaya asked his ministers to narrate his father’s story. Listening to their detailed narration, Janamejaya was in tears. He said, “Takṣaka ’s intention was to kill my father. If his intention was merely to bring fulfillment to Śṛṅgi’s curse, he would have bit my father and gone away. Kaśyapa would have revived him. But he didn’t do so. He played on Kaśyapa’s mind, sent him off, and then came to destroy my father. Therefore, the performance of the sarpa-yāga is justified. It will not only make me happy but will also please Uttanka. Make the appropriate arrangements!”

The story goes that the architect of the yajña-mantapa (the enclosure in which yajña is performed) noticed bad omens during its construction. He declared, “This yajña will never be completed. A brāhmaṇa will be responsible for its abrupt end.” Therefore, Janamejaya made a strict order – “Don’t allow anyone into the yāga-śālā until the yajña is complete.” [Here, the words yāga and yajña have been used interchangeably.]

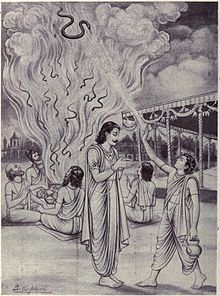

The arrangements were made accordingly and the yajña started. Several varieties of serpents of different colours and types started falling into the fire of the yāga. When the heat of the yajña started affecting Vāsuki and his family, he called his sister Jaratkāru and said, “Send your son Āstīka and make him stop the sarpa-yāga. He was born only to rescue us from this predicament.” Āstīka reassured Vāsuki and went to the yajña-śālā. The gate-keepers would not let him in. Then even at the doorstep, Āstīka started praising the yajña, the person conducting it, and the ṛtviks officiating it. This gladdened Janamejaya and he said, “Although young, this person at the door seems to be intelligent. Let him in.” He welcomed him and asked, “Tell me what you wish for. I shall give it to you.”

In the meanwhile, except Takṣaka most other snakes had fallen into the fire of the yajña. However, Janamejaya’s enmity was primarily with Takṣaka . He had thus commanded the ṛtviks that Takṣaka must be forcibly brought and offered to the fire. Sensing imminent danger to his life, Takṣaka took refuge in Indra. Having learnt this, the ṛtviks uttered the mantra ‘sendrāya takṣakāya svāhā’ (“We offer Takṣaka along with Indra!”) as they performed the ritual. Indra was thus forced to come along with Takṣaka . Indra, however, left Takṣaka midway in the skies and returned to his abode. At the same time, Āstīka said, “O respected king! Let the yajña stop at this point! This is all I wished for! I don’t ask for any gold or silver.” Janamejaya was bound by his word and had to follow the dharma of a yajña, thus having to fulfill Āstīka ’s wish. The sarpa-yāga was stopped before completion. Takṣaka survived. Āstīka was happy.

Śaunaka was enthralled listening to the story. He asked the Sūta-Paurāṇika, “You have finished narrating all the stories starting from the lineage of Bhṛgu. Please recount the strange and fascinating tales that Vyāsa and others narrated during the time of the sarpa-yāga.” The Sūta-Paurāṇika Ugraśrava said, “All brāhmaṇas except Vyāsa narrated stories from the Vedas but Vyāsa always narrated the story of Bhārata alone.” Śaunaka then asked, “If so, please tell us the Bhārata story that you heard from Vyāsa.” Ugraśrava said, “So be it! I shall narrate the elaborate story of the epic Mahābhārata as retold by Kṛṣṇa-dvaipāyana. I too am eager to recount that very tale.” Saying so, he started the Bhārata epic.

Thus, the fifty-third adhyāya and the Āstīka (upa-) parva comes to an end.

To be continued.

Thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for his astute feedback.