It could be argued that early in the colonial period, there was genuine interest to study India, and the West did produce some rigorous work in the area in the form of travelogues, comparative religion, military accounts and India-specific formal academic scholarship. Among others, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, Niccolao Manucci, Eliot and Dawson, Robert Sewell, and James Todd have left behind invaluable treasures after years of observation, experience, study, travel and other painstaking labors aimed at uncovering our past. Later scholars, thinkers and writers have continued to build upon their edifice.

Colonel Colin Mackenzie, the first Surveyor General of India easily, deservedly belongs to this galaxy of eminence. Prof. T V Mahalingam’s compelling introduction to Col Mackenzie is a good place to begin:

…it is necessary to recall the contemporary climate of [Mackenzie’s] times. To the Occident, the Orient was a dark continent inhabited by semi savages with no civilization or culture. A study of Orientology was the hobby of the eccentric. What was accepted as normal was to join the East India Company, make easy money by means fair or foul and return home to live in comfort or participate in politics on the security of the fortune made in India. That a few of the Company’s servants did not tread this golden path to fortune, but chose on their own, prompted by the love of learning, ‘to discover the east’ for the benefit of…the east itself was a lucky accident of great historical value.

Indeed, for the true seeker, India has since antiquity, offered something for everybody according to his or her disposition and ambition. Even for Katherine Mayo, the “gutter inspector” according to Gandhi, and for her intellectual descendants of today who dominate the Western academia and media.

The story of Col Colin Mackenzie—a highlander born in 1754 in Stornoway on the Island of Lewis, Scotland—begins when he was enlisted to assist in preparing the biography of John Napier, the inventor of logarithms.

Testifying before a Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Affairs of the East India Company, Sir Alexander Johnston says that Colin Mackenzie was:

…much patronized, on account of his mathematical knowledge, by the late Lord Seaforth and my late grandfather, Francis, the fifth Lord Napier of Merchistoun. He was for some time employed by the latter, who was about to write a life of his ancestor John Napier, of Merchistoun, the inventor of logarithms, to collect for him…[information] from all the different works relative to India, an account of the knowledge which the Hindoos possessed on mathematics, and of the nature and use of logarithms. Mr Mackenzie, after the death of Lord Napier, became very desirous of prosecuting his Oriental researches in India. Lord Seaforth, therefore, at his request, got him appointed to the engineers on the Madras establishment.

And so Colin Mackenzie landed in Madras on 2 September 1783 when Warren Hastings was the Governor General of India. And remained in India till his death on 8 May 1821. He was buried at South Park Street Cemetery, Calcutta.

And left behind a vast treasure of original manuscripts, inscriptions, coins, translations, maps, drawings, and literary works in all South Indian languages and Sanskrit. To get an idea of what Mackenzie had accomplished over thirty eight years, we can turn to David M Blake:

One of the most wide ranging collections ever to reach the Library of the East India Company is formed by the manuscripts, translations, plans, and drawings of Colin Mackenzie, an officer of the Madras Engineers and, at the time of his death in 1821, Surveyor-General of India. Mackenzie spent a lifetime forming his collection which is exceptional, not only for its size, but also for the fact that materials from it are to be found in almost every section of the India Office Collections including Oriental Languages, European Manuscripts, Prints and Drawings, and Maps. Including manuscripts in South Indian languages held in the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library in Madras…. According to Mackenzie’s own estimate, no fewer than fifteen Oriental languages written in twenty-one different characters…according to a statement drawn up in August 1822 by the well known orientalist Horace Hayman Wilson who, after Mackenzie’s death, volunteered to undertake the cataloguing of the collection, there were 1,568 literary manuscripts, a further 2,070 Local tracts, 8,076 inscriptions, and 2,159 translations, plus seventy-nine plans, 2,630 drawings, 6,218 coins, and 146 images and other antiquities.

This entire corpus has since been known as the Mackenzie Manuscripts or the Mackenzie Collection.

Surveyor Par Excellence

Col Colin Mackenzie made his mark in the Anglo-Mysore wars, and his contribution and role especially in the final Anglo-Mysore war forms a substantial basis for Col Marks Wilks’ definitive work Historical Sketches of the South of India in an attempt to trace the History of Mysore.

Marks Wilks cites Mackenzie’s two-volume, Sketch of the war with Tippoo Sultan, a detailed record of his experiences in the war in a threefold capacity as a surveyor, strategist and a participant. However, Prof Mahalingam notes that Mackenzie’s book “has apparently disappeared altogether.”

However, as both Lord Cornwallis and later, Lord Wellesley and other superiors engaged in the Anglo-Mysore wars glowingly testify, the extraordinary military successes of the British in South India owed significantly to Mackenzie’s labours: most notably, for ushering in the ultimate destruction of Tipu Sultan in 1799 and the submission of the Nizam of Hyderabad to the British in 1798 as we shall see.

Discovering his Lifelong Goal

Soon after his arrival in Madras, Col Mackenzie was called to visit Madurai where Samuel Johnston and his wife Hester, who was studying Hindu logarithms as part of her contribution to John Napier’s biography. Mrs. Johnston introduced him to the Madurai Brahmins “who were supplying her with information on the Hindus’ knowledge of mathematics.”

The more he interacted with these Brahmins, the greater his astonishment and admiration for their expansive learning, which “fired his interest in Indian antiquities.” This became the basis of his lifelong mission, and “the favourite object of his pursuit for 38 years of his life.”

In Madurai, he drew up a plan of making a collection of these antiquities, which later became the “most extensive and the most valuable collection of historical documents relative to India that ever was made by any individual in Europe or in Asia.”[Emphasis added]

But this plan would have to wait for a few years before being put in motion. In the interim, official duty beckoned.

Between 1790-92, Mackenzie was commissioned to “methodize and embody the geography of the Deccan.” This was because of the splendid results he had shown in 1788 in surveying the entire region from Nellore to Ongole and as far as Chintapalli across the river Krishna.

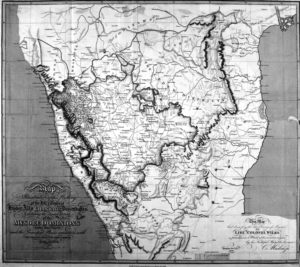

Recognizing his abilities as an expert geographer and surveyor, Lord Cornwallis tasked Mackenzie with significant responsibilities in the Third Anglo-Mysore War. Mackenzie successfully wrested the Palghat, Bangalore, Nandidurga and Savanadurga forts earning military distinction. Post the war, he began an extensive survey of regions as vast and diverse as Kadapa, Kurnool, Nallamalla (mountain ranges), Zeramulla, Krishna, and Pennar rivers. After three years of ardous work, in 1796, he submitted for the first time, “a general map of the [Hyderabad] Nizam’s dominions.”

Thus, in no small measure, it was this intimate knowledge of the geography of South India that won the British their military successes among other factors.

Meeting the Cavelly Brothers

And it was during this period of surveys that Colin Mackenzie’s plan took life and shape. The major breakthrough occurred in 1795-96 in the form of one Cavelly Venkata Boriah, “a young Brahmin who proved to possess a ‘happy genius’ for gathering information from Indians of all castes and tribes, and for organizing Mackenzie’s team of Indian helpers to do likewise.”

Boriah was a “prodigy” who was proficient in Sanskrit poetry at the age of ten and had mastered Telugu, Persian and Hindustani grammar. Mackenzie appointed him as a research assistant. Boriah traversed “dreary woods and lofty mountains” and “collected various ancient coins, and made facsimiles of inscriptions in different obsolete characters. When he deciphered the Hala [Old] Kannada characters inscribed on a tablet found at Dodare, which is now…in the museum of the Asiatic Society,” Mackenzie was “highly gratified and put his name on it.”

However, tragedy struck when Boriah suddenly died of apoplexy at the young age of twenty six. So moved was Mackenzie that he ordered a monument to be erected in his memory with a suitable tribute etched therein.

Boriah was succeeded by his younger brother Cavelly Venkata Letchmayya [Lakshmayya] as the Head Interpreter of Mackenzie. Other prominent members of his team included Abdul Aziz, Baskariah, Moba Row, Ramaswami and Sivaramaiah for their prowess in Tamil, Telugu and Kannada.

Survey of the Mysore Region

After the fall of Tipu Sultan in 1799, and with the Nizam ceding some of his districts to the British in 1800, the British undertook a massive survey of the entire region. Mackenzie headed the effort described as a “complete survey of Mysore in all its aspects including its geography, history and antiquities.”

The survey was finally completed in 1807 and its report, submitted in February 1808, was truly exemplary and one of its kind. However, recognition let alone appreciation was not forthcoming until 1810 when the Evangelist MP, Charles Grant, then Chairman of the East India Company lavished praise on Mackenzie.

The Company added in its note that Mackenzie had supplied the “real history and chronology” of India as well as the “genius of [Indian] past government” and unearthed possible evidences of “remote eras and events…monuments, inscriptions and grants preserved either on metals or on paper.”

But Mackenzie was unstoppable. Even as his Mysore Survey was tabled, he had persuaded the Madras Presidency to complete the survey of the remaining Ceded Districts [by the Nizam]. And by the time he wrote to Johnston in 1817, he had finished surveying 70,000 square miles of territory in all of South India.

Stint in Java

In July 1811, Mackenzie was ordered to go to the Dutch colony Java, which was now in French hands thanks to Napoleon annexing Holland. After a hard battle, the British wrested Java.

Mackenzie now embarked on an extensive survey of Java. While he was camped at Surakarta, he “seized the opportunity of gratifying his antiquarian tastes” by visiting Prambanam and wrote an extensive, scholarly essay in the “Transactions of the Literary and Scientific Society of Java.”

He also commissioned an intensive excavation of the Buddhist shrine in Borobodur, discovered the nearby, ancient temple of Tjandi Mendut and Tjandi Kalasan, another ancient Hindu temple. And while still in Java, he married a Dutch lady named Petronella Jacomina Bartels in Batavia, which corresponds to today’s Jakarta. Mackenzie was approaching sixty at the time.

He finally returned to India in July 1813, showing the world exactly how much one could accomplish in just two years.

First Surveyor General of India

In India, he went to Calcutta and applied for a nine-month leave during which time he travelled first to Benares and then Lucknow, Agra and Delhi and the Himalayan ranges that divide India and Tibet. As was his habit, he made copious notes, collected ancient coins, manuscripts, inscriptions and sculptures.

In 1815, the East India Company abolished the offices of independent Surveyor Generals in various Presidencies and created the post of Surveyor General of India. Colin Mackenzie became its first head, now operating from Madras.

In 1816, he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society and promoted to the rank of Colonel.

However, his health steadily worsened even as he made another trip with his wife to Calcutta in 1817. His numerous letters to Johnston mention this as also his fear that he wouldn’t live to realize his dream, “in this last stage, preparatory to my return to Europe” of giving a “condensed view of the whole collection and a catalogue raisonne of the native manuscripts and books, etc.”

His return to Europe was not to be. As a promotion of sorts, he secured pensions for all his longtime, devoted assistants in Madras. Cavelly Venkata Letchmayya secured an additional land grant for his services and was also earmarked a sum in Mackenzie’s personal will.

Death and Legacy

Col. Mackenzie became bedridden in November 1820 and despite several efforts that stretched for more than a year, failed to make progress. On 4 May 1820, he was “urged to go to the coast” for treatment and recovery. However, on 8 May 1820, he breathed his last at his residence in Chowringhee.

Colin Mackenzie’s legacy is mixed. He was undoubtedly a product of, contributed to and furthered British imperialism in India. Specific criticism about how Mackenzie acquired some parts of his collection is also worth mentioning. For example, Robert W. Wink who talks about the “Jesuit policy of Theft, Confiscation and Purchase” of Indian Books, the particular case of Mackenzie becomes “the most impressive orientalist explorations [that] were collaborative, unofficial and voluntary. Among these, none matched the enormous privately funded venture by Colonel Colin Mackenzie. His teams of Maratha Brahmin scholars begged, bought or borrowed, and copied, from village heads, virtually every manuscript of value they could finally acquired. Collections so acquired, reflecting the civilization of South India, manuscripts in every language, became a lasting legacy – something still being explored.”

While the Western-colonial theft of valuable knowledge in medicine and other sciences is well-documented, it would be unfair to level a blanket charge of this nature on Mackenzie’s collection as we shall see in the next part of this series.

But the actual content of his massive and invaluable collection shows him as a genuine student and aficionado of Indian antiquity in its various hues and facets and remnants.

And thus the question remains: do we thank him or despise him?

T V Mahalingam’s assessment of Mackenzie’s work throws some light:

Mackenzie was a pioneer in his field. There was no precedent for his special field of research into the antiquities of India…he stood alone. The results of his work were a topographical survey of over 40,000 square miles, a general map of India and many provincial maps, a valuable memoir in seven volumes containing a narrative of the survey…of historical and antiquarian interest.

And equally, Blake does too, in his assessment that

Mackenzie and his agents certainly collected a wide range of materials. Not the least of their contributions was to set down in writing a large body of oral tradition which might otherwise have been lost.

The assessment of the value of the Mackenzie Manuscripts will be discussed in the second part of this series but suffice to say that they offer us the primary sources for the study of the political, economic, and administrative history of South India post 1600 CE with a high degree of historical accuracy. They contain such minute details as information maintained in village registers, land grants to temples, pilgrimage centres located across remote towns and cities across South India. A careful study of these primary sources might help reconstruct and/or reveal hitherto unknown facts of South Indian history.

And I agree with Prof. Mahalingam that the best tribute to Colin Mackenzie is his own words:

All great and low, have their troubles, and we little men should not complain if we have our share. The only remedy is to move on in tranquility, guided by truth and integrity to the best of our judgement and avoiding all intrigue and chicanery.

Tailpiece

After Colin Mackenzie’s death, his wife offered his collections to the Bengal Government for a sum of Rs. 20,000. Eventually, the Bengal Government paid her Rs. 1,00,000 after getting them evaluated by the law firm Palmer & Co.

The seven volumes of Mackenzie’s memoirs that Prof. Mahalingam mentions have been lost forever.

To be continued...

A version of this article was published in Daily O.