The interpretation and elaboration that Mantap does for the line raṅganyātakè bārano is extraordinary. He shows several different emotions of the gopikā as he enacts the line. O Raṅga! Why haven’t you come? – Do you think I am ugly? Or has our love lost lusture? Have other women captured you more than me? Or am I hallucinating? I am not able to bear this! Why is he so proud? Why is he arrogant and insensitive? Why do you still ignore? – in his abhinaya for this line, all the thirty-three vyabhicāri-bhāvas along with eight of sthāyis- bhāvas and eight sāttvika-bhāvas rush on to the stage as though in a competition to get seen. When such is the case, it is hard to capture these subtle nuances through words.

For the line, ‘Raṅganyātakè bāra, tiṃgaLāyitu pūra<>’ (Why doesn’t my raṅga come? It has been a month already!) Mantap shows the lapse of a month in a very creative manner. He makes the heroine count the number of days with the fingers on her hand. When the fingers do not suffice, she starts counting with her toes. She also observes the lines she has made on the wall to keep a count of the days. She counts the number of dried-up flowers and notes the waxing and waning periods of the moon. She still feels that she has miscounted the days and a month has not yet elapsed. She thinks that her neck has grown tall as she has waited for him with a stretched neck, looking his way all the while; her eyes have gone dry; her limbs appear to be giving away. She feels – jāji-malligè hūvu sūjiyāytu, bhojana viṣavāytu – jasmine flowers have become needles and the food I eat has turned into poison. Mantap creatively brings in several vyabhicāri-bhāvas while portraying this line. The agony and pain of the heroine are delicately depicted. He shows how the sandalwood paste is not softening the emotions and the rays of the moon are piercing her heart. The heroine tries sending a maid to search for Kṛṣṇa, imagines that he is coming, has a mixture of love and devotion, irritation and anger on her face; when he finally comes, she puts a garland around him and that is big enough to accommodate her too; she gets the feeling of advaita as she is embraced by the same garland along with her beloved, is in pain as she comes out of the garland and is back to dvaita, says ‘You haven’t come for so long! Just see!’ – she applies sandalwood paste on his feet, presses her forehead to his feet and the sandalwood paste becomes the tilaka on her forehead… and it goes on.

The poem has got only four lines –

raṅganyātakè bārano aṅganāmaṇi

raṅganyātakè bāra? tiṃgaLāyitu pūra! beLdiṃgaL bisilāyitè!

jāji-malligè hūvu sūjiyantāyitu| bhojana viṣavāyitè||

bāle nīpogigopālana baraheLe| bālendudharasakhana ||

Mantap performs abhinaya for over thirty minutes for just four lines.

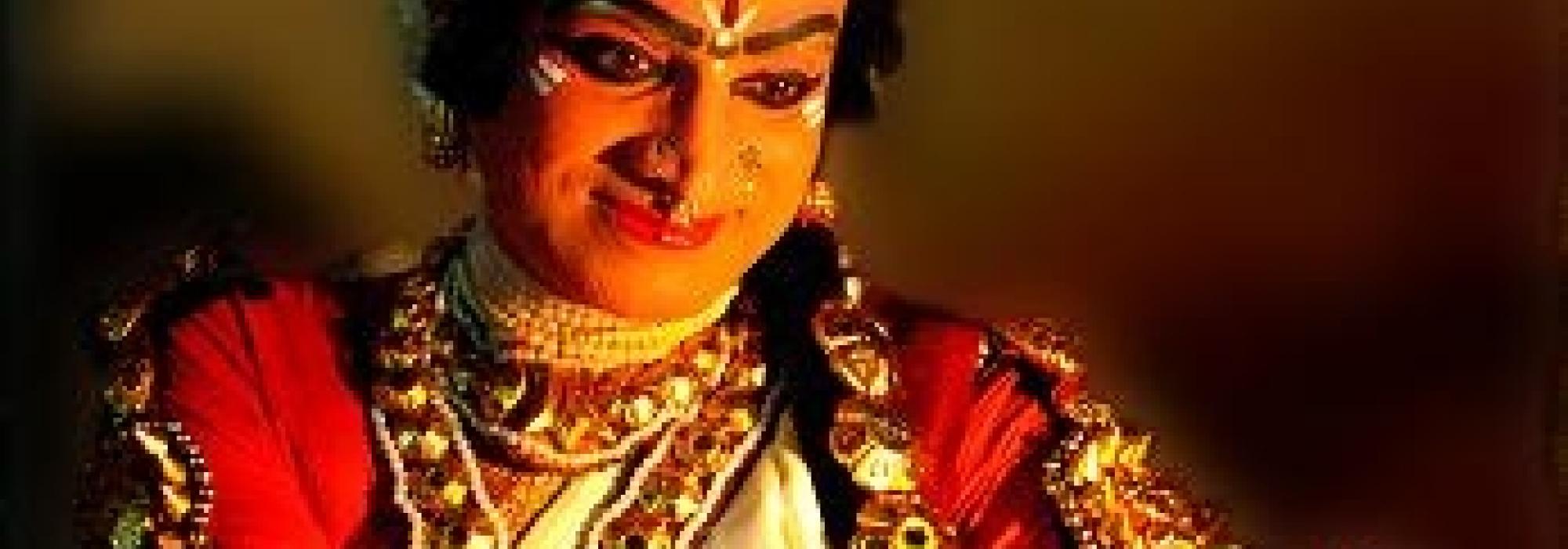

When such is the calibre of Mantap, he can do wonders when he gets full-fledged sāhitya for the characters of Viṣayè, Pūtanā, Śūrpanakhā and others. There is a lot of hāsya, śṛṅgāra and śṛṅgārābhāsa that Mantap brings out in depicting such characters.

Viṣayè’s abhinaya for the lines noḍi nṛpakumārana and pogolanurubādhègè are sublime. He brings in so much of sāttvika in āṅgikābhinaya.

arare tappihudòṃdakṣaradi– He shows Viṣayè jumping up in joy when she realises that probably there is an error of one syllable in the letter written. It brings us to recall his brilliant abhinaya for the line – ènagilla bhayakāraṇa as an abhisārikā. Āṅgika, vācika and sāttvika blend together very well in bringing a myriad possible interpretation.

Śūrpanakhā addresses Śrī-rāma using the lines rāghava-narapate. The variety of emotions and interpretations that Mantap brings for this phrase is extraordinary. He brings in tender human emotions even in the character of a rākṣasī. The contrasts between mānava and dānava, like the play of light and darkness and the śṛṅgārābhāsa it results in are worth noting. While this is a case of romantic love, the dilemma that Pūtanā faces, being filled with opposing emotions of raudra and vātsalya is depicted by Mantap in an impactful manner. The depiction of the two rākṣasīs - Śūrpanakhā and Pūtanā - is very interesting and is a mix of several different emotions.

Close to the end of the Bhāminī production, the heroine, as a khaṇḍitā-nāyikā, throws her husband away from her house. At this juncture, before she displays repentance as a kalahāntaritā, she wishes to cool down the heat of anger within her. She drinks water from a pot to cool herself down; as though that was not enough, she pours down water on her body; as she is still not able to calm down, she smashes the pot on to the ground; in the broken pieces of the pot, she sees her own broken relationship; she then tries to pick the pieces up, patch them together but is unable to do so; she then finds a drop of water in a broken piece of pot; licks the drop of water with her tongue; leaves the stage, dejected and repenting. The detachment and repentance suggested by silence at this stage turns into helplessness, which is depicted through the rāga Bhairavī – a rāga that suggests pathos – in the next scene.

~

Let me now recall a few instances where Mantap was posed with unexpected challenges on the stage. The challenges were, at times, connected with the green room and at times with the audience. The manner in which he creatively circumvents the apparent problems is astounding. Yakṣagāna artistes, usually, react to such untoward and unforeseen circumstances through words. But that merely amounts to vācika. However, Mantap’s creative reaction to such situations is through sāttvika.

Yakṣa-darpaṇa was once performed in a farmhouse. The stage and the green room were far apart. Each time, Mantap had to walk a long distance and he creatively filled the distance with his rich abhinaya. Most of the artistes have difficulty in entry and exit but Mantap never faced any difficulty with these. His entries and exits were highly creative and changed day by day in a manner that pleasantly surprised me. On the particular day, when Viṣayè had to appear on the stage, he took more than five minutes to reach the stage from the green room. The stage was surrounded by vegetation. Mantap, as Viṣayè, roamed around the garden and actually plucked flowers as he danced gracefully moving towards the stage. Thus, his entry appeared very natural to the character of Viṣayè. It was very impactful. In a sense, the whole garden had become his stage.

Once, when he had to perform for the song raṅganyātakè bārano, his anklet got loosened and fell off at the entry. He entered as though he had not noticed it. As a gopikā in separation, he searched for Kṛṣṇa for a while and saw the fallen anklet as though he noticed it only then. Excited, he rushed towards it, pretending to think that it was Kṛṣṇa’s anklet. He then enacted as though the gopikā realised that it is her own anklet – in all dejection and anger, he depicted her throwing away the other anklet too!

In another occasion, the organizers had placed a big lamp for the inauguration and that occupied a major portion of the stage. Mantap had to perform raṅganyātakè bārano on this occasion too. He started his exit like a gopikā who was about to light the evening lamp and started lamenting – why hasn’t Kṛṣṇa come even at this juncture of the evening? What is the use of this lamp when my life is dark because of his absence?

When the movement ‘ManèyaṃgaLadalli Yakṣanāṭya’ (‘Yakṣagāna at your doorstep’) took off, Mantap started performing in remote hamlets and in the houses of villagers. His creativity never got suppressed by the limitations and oddities present there. Once, he was portraying a happy Yaśodhā who had to joyfully exit carrying Kṛṣṇa on her shoulders. The exit could have been executed well had it been a usual stage in an auditorium. But on the particular day, the surroundings could not allow for such an exit. The creative Mantap was not worried. He quietly slipped into another small room next to the dais and placed the imaginary Kṛṣṇa there; he enacted as though toys were spread out in front of the baby and Yaśodhā was instructing him that he should sit there and play while she would complete the domestic chores. Communicating this, Mantap quietly went backstage, which was also filled with connoisseurs and his exit was similar to the hurried movement of a housewife rushing towards her household chores. This performance convinced all the connoisseurs that Kṛṣṇa was still playing quietly in the small room. The audience had tears of joy. The members of the household declared that from then on, the particular room where Yaśodhā had dropped off the baby Kṛṣṇa would be their place of worship - pūjā-gṛha.

In another house, a small cupboard that was thought to be an impediment for the performance was creatively used by Mantap to hide the peacock feather. It also worked as a niche where Kṛṣṇa would rush in and conceal himself because he wasn’t interested in bathing. At other times, it was used as a place to safekeep milk and curd away from Kṛṣṇa’s eyes.

In this manner, every obstacle for the performance would become an object of spontaneous creativity. To sum up, a great artiste will transform the whole world as his stage and sublimate the real world into an ethereal place of divinity. This brings to our minds, the words of Rājaśekhara – astu vastuṣu mā vābhūt, kavivāci sthito rasaḥ - irrespective of the presence or absence of aesthetic appeal in the subject matter of the poem, its artistic expression will always be replete with Rasa.

Therefore, it is only partially true that I conceived Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna and directed it. In reality, all our artistes work as a team and regularly treat us with rich aesthetic experience – all our efforts ultimately culminated in Rasa. Such freshness is the hallmark of Yakṣagāna and it is the secret of Indian art.

This series of articles are authored by Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh and have been rendered into English with additional material and footnotes by Arjun Bharadwaj. The article first appeared in the anthology Prekṣaṇīyaṃ, published by the Prekshaa Pratishtana in Feburary 2020.