Preface

That the Vijayanagara Empire, right from its foundations resting on the amalgamation of the Brahma-Kshatra spirit, stood not only as the bulwark against rampant Muslim invasions from North India, but also swelled to become one of the greatest empires in the world is well-known. Its geographical spread apart, almost every trader, traveler and in general anybody who had any business with it testify to its unrivalled material prosperity.

Yet that fateful, final battle of Talikota crushed this mighty empire and destroyed along with it valuable firsthand accounts and/or evidences that testified to its equally magnificent and picturesque social and cultural life, so to say.

Beginning with this essay, an attempt is made to trace primarily the cultural, artistic, literary and social life of Krishnadevaraya’s era because that is unarguably the period the Vijayanagara Empire reached its zenith. This series is an adaptation of (the late) Sri Rallapalli Ananthakrishna Sharma’s lecture at Penugonda titled, Rayara Kaalada Rasikate on the occasion of Sri Krishnadevaraya’s birthday celebrations.

There is probably no extant work that provides a firsthand account of the day-to-day life of the society and people during Krishnadevaraya’s regime. However, three major Telugu literary works, composed in the Champu[i] style do throw some light on this:

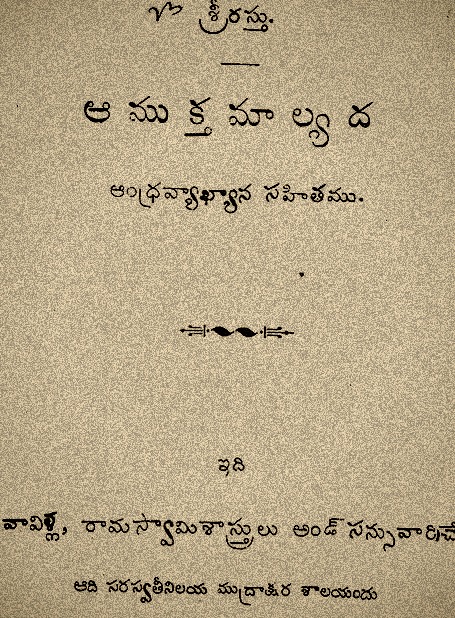

- Aamuktamaalyada authored by Krishnadevaraya

- Manucharitra authored by Allasani Peddana

- Parijaaatapaharanamu authored by Nandi Timmana

These works are fictional comprising Puranic, epic, supernatural, and fantastic elements and as such, offer little for those seeking hard realism. Yet, the authors[ii] who wrote them also drew richly from their own contemporary society and daily life in all its variety. And so, while it is tempting for modern literary critics to dismiss all of these as creations of fanciful imagination with a broad brush, one needs to ponder upon a simple fact: the society of the authors who wrote these works lived, traveled and experienced was real. And so, it is impossible to dismiss everything their work contains as pure fiction and nothing else.

For the connoisseur of pure art or literature, discussions about whether some element therein is real or unreal, credible or incredible are futile because these elements are not items that are tangible, much less available as physical products. Therefore, viewed objectively, every work of literature will contain elements that reflect the impulses, mindsets and behaviors of people, and societal specifics and mores belonging to the period in which its author lived. For instance, Kumaravyasa’s Kannada epic, Karnata Bharata Kathamanjari, has Buddhists and Lingayats attending Draupadi’s swayamvara. Equally, although the three Telugu works cited earlier are populated by supernatural or divine beings, the poets who wrote them are from our own world; and so, those works reveal ample traces of this world. No matter how supernatural or otherworldly the poet tries to elevate his work, it cannot be cast to a height beyond the earthly air.

Given this, it’s not difficult to get a picture of the society, culture and connoisseurial life of Krishnadevaraya’s period from these three books. In this essay, the word “connoisseur” is used as a translation for the word “rasika,” which variously means “epicurean,” “aesthete,” and “enjoyer.”

Equally, a connoisseur who takes enjoyment as an end in itself becomes an unbridled hedonist. For our purposes, we can consider a connoisseur to be one who takes equal delight in the enjoyment of the senses as well as in non-sensual aspects like bhakti, sacrifice and renunciation. Enjoyment is a mental and emotional attitude, and not something that depends on external stimulation or objects.

And so any attempt to heighten this mental attitude towards enjoyment is a defining quality of being a connoisseur. The more refined the connoisseur, the nobler his spirit. An unrefined connoisseur is akin to a walking corpse. His love is deception, his enthusiasm phony. And so, when one examines the epicurean life of Krishnadevaraya’s era, we’ll know the true extent of our pretensions to being connoisseurs.

Traditionally, our ancients listed eleven items as enjoyments: home, dress, jewelry, sandal, flowers, tamboola (paan), bed, woman, food, drink and bath. We now need to recount the perspective our ancients had towards these enjoyments because perspective determines attainment.

Larger than Life

People of Krishnadevaraya’s time weren’t content with petty things. Their desires and aspirations in every aspect of life was prodigious, and they had a digestive capacity to match. In an age of overflowing plenty, it was no surprise that they sought and obtained the best in class of whatever they desired. And once obtained, they enjoyed them to the fullest. Indeed, when munificence was at their command, they were ignorant of the existence of little.

Neither was this lavishness limited to the realm of material enjoyments. It flowed, it reflected in their world of emotion as well.

A traveler from a different land passing through the kingdom would take shelter in one of the cities till the torrential rain stopped. The typical topics for discussion with other folks would include things like the relative prowess and strength of say the commander of the elephant force or that of the cavalry or infantry. People would quickly take sides, the argument would escalate, and if it wasn’t amicably resolved, they’d come to blows. And the moment the rains stopped, they’d depart, amicably, as if nothing had happened, says the Aamuktamaalyada.

In whatever activity they embarked upon, in purchase, in argument, in war, in manners and in social life, they didn’t have the lax, sloppy attitude of, “let things be how they are, how do we care?” They were thorough in and out. Given this, it’s impossible to conceive that both the aspirations for and objects of enjoyment that these people pursued was anything but petty or little.

In the ensuing parts of this series, we shall examine these details one after the other.

Note

[i] A mixture of prose and poetry passages, with verses interspersed among prose sections.

[ii] Both Allasani Peddana and Nandi Thimmana were court poets of Krishnadevaraya. Both were honoured as being among the Ashtadiggajas (literally: Eight elephants, owing to their literary prowess).