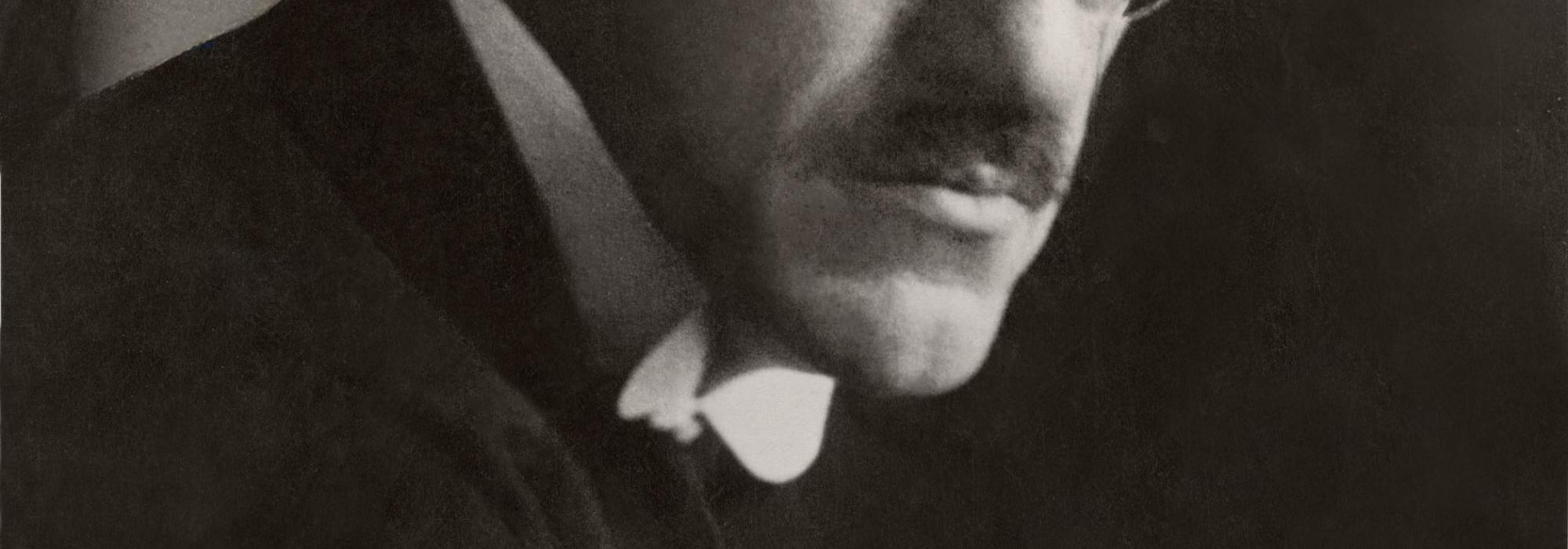

Edwin Montagu

In matters connected with politics and the social relationships, Sastri wanted to make sure that his speech was clear, credible and did not lead to debates later on. Under such (rare) circumstances, Sastri put in a lot of thought and prepared himself for his lecture, ensuring that the content was accurate. In about 1933, a statue of a person called Edwin Montagu was erected in Bombay. Montagu was a minister appointed by the British to take care of matters related to India. In those days, Montagu had helped the Indians to the greatest extent possible for an English politician. We see his name in the set of political reforms which came under the head ‘Montagu-Chlemsford Reforms’. It was Edwin Montagu who made the declaration of the British Government known, that they intended to provide responsible government to India.

As Indians in the Bombay Presidency wanted to remember such a person with gratitude for the assistance he had provided, they though of erecting the aforementioned statue. Srinivasa Sastri knew Montagu in person. He knew his heart very well. Thus, the statue committee felt that Sastri was the right person to unravel the statue and invited him for the purpose. After accepting the invitation, Sastri wrote a request letter to a few of his friends.

“I have agreed to inaugurate Monatgu’s statue. I will need to deliver a speech on the occasion. I will need your counsel regarding what should and should not be spoken on the occasion.”

The above is the summary of the letter he wrote. I was one among the people who received the letter from him. I expressed a pleasant surprise in my written reply to him. “Should I give you suggestions?” – I asked. He did not drop the matter there. He wrote a reply – “I have not written the letter merely as a gesture of courtesy. I would like to know the topic in its entirety and contemplate upon it”. I jotted down a few points that came to my mind and sent it to him in reply.

After about two to three weeks, the day on which Sastri was to set out to Bombay arrived. Around the same time, I was to go to Belagavi for the [Kannada] Sahitya Sammelana. Sastri and I travelled together until Belagavi by train in a second class compartment. We happened to share our compartment with a couple of others until we reached the Hindupur station. They got off the train at Hindupur and it was only the two of us who remained back. Thereafter, the coach was entirely ours.

Sastri then started speaking: “Let us speak about Montague now. I have gone through all the suggestions given by my friends and have noted down points that I would like to include in my speech. I will now rehearse my speech treating it as a first draft before you. Listen to it”. He started in this manner and spoke unhindered. By the time we reached the station just before Belagavi, his ‘trial-lecture’ was over.

Four days after this, the statue got inaugurated in Bombay. His lecture on the particular day was published in the newspapers. There was absolutely no difference between what Sastri spoke there and what he had spoken before me as a ‘rehearsal’. It was the same to about ninety-nine percent. His memory was so sharp.

Sastri’s Memory

Sastri worked in a similar fashion even when he dictated entire essays. He would dictate about twenty to thirty sentences at a stretch. He thought in detail and dictated without any hurry. After about a quarter or half of an hour had elapsed in this manner, an obstacle would arise – a friend, a letter or an incident. The obstacle would take about fifteen to thirty minutes to pass. After that, Sastri would start again. What was fascinating here is – suppose he had stopped mid-sentence or in the middle of a word while dictating before the interruption happened, he would pick it up right at the spot once the impediment had passed. It would seem as though there was nothing that had interrupted us in the process. The new phrases dictated would gel well with the previous and the next sentences. As his memory was so sharp, he needed no prior preparation for anything.

His immense vocabulary was a great strength. His treasure trove of words was vast. It, however was no exuberant. Sastri never employed rare words in his language. He used words that were in vogue in everyday language and which were easy for common people to understand. But, the usage of such words was also with some forethought.

He had told me the following quite a few times – we will need to discriminate between what is 'Truly Ornamental' and what is 'Meretricious' in our vocabulary. We cannot keep aside embellishments in language. We will need to employ literary ornamentation and figures of speech to convey the intended meaning accurately to the listener. At times, we will need to use them to create a certain impact on the listener’s mind. However, when we employ such ornamented language, we should think on the following questions – is our usage helping our purpose or is it merely cosmetic in nature? Is it natural or artificial? We will need to closely examine these aspects.

I'll try to describe in a couple of words the impact Sastri’s speech had. However, I don’t mean to put them to practical use. Is it possible to describe the colours of the rainbow that appears in the sky? Will we be able to capture the colours of flowers like rose in our words? Will we be able to adequately describe the nature of good music? Similar is the difficulty in describing a good orator. Words merely flow out of his mouth. It creates different kinds of blissful impact on the minds of the listeners. The impact of the orator is related to the listener’s internal landscape. It is difficult for a person like me to revive it in an external medium.

Yet, if there are youth who are curious to know about the characteristics of Sastri’s speech, I shall describe it by giving broad and approximate outlines

Catussūtrī (Four Cardinal Principles)

- Manaḥprasannatā (Equanimity of mind): Sastri contemplated on the matter he intended to present over and over again and he would come with a chronological manner in presentation. This clarity in mind is the first characteristic feature of his speech. Once he got up to speak, he wouldn’t fiddle for words or display any uncertainty in his speech by introducting ‘ha-s’ and ‘hu-s’ while speaking. His speech was devoid of such distortions. What was to be said was clear in his mind. This internal conviction is of utmost importance.

-

Śabdasauṣṭava (Structured usage of words): He would pick the words from his immense vocabulary that would go well with the context.

- Vākyadhoraṇa (Impactful sentences) – A lecture should blossom the mind of the listener just as a friendly conversation with a group of intimate friends does. The speech should contain the following and associated qualities – hāsya (humor), anunaya (convincing), udbhodana (education) and pracodana (motivation). The structure of the sentence and the association between the different parts of the sentence should blend in a certain manner – this, in itself is an interesting aspect to contemplate upon.

- Kaṇṭha-dhvani (voice): Among the fortunes that the Divine had conferred upon Sastri, good voice was an important one. His voice was pleasant to hear. Whether he spoke in English, Sanskrit or Tamil, the flow of his speech delighted the ear. It is not the kind of tone that would put you to sleep, but it is something that could wake someone up. In case the brain was lethargically trying to switch itself off, the magical touch of Sastri’s voice could wake it up.

An Impromptu Speech

Once, a friendly get-together of the Scouts was arranged on the Western storey of the Tipu Sultan’s palace in Bangalore. The party was filled with delicacies and was rich with fresh fruits and flowers. There was no lecture organised that day. The agenda only contained felicitation of Srinivasa Sastri with a garland and other embellishments. But, our K.H. Ramayya was there, in deed! Ramayya was the main person behind the day’s celebration. At the end, he stood up and said the following in a comical manner: “When we have gathered here brimming with enthusiasm to listen to something nice, is our guest so cruel that he doesn’t understand our hearts?” Sastri let out a gentle smile and gave a speech which lastest about ten to twelve minutes.

Among the hundreds of speeches of various people that I have heard, Sastri’s has its own unique style. It is unlikely that none of Satsri’s other speeches were as brilliant as this particular one. Humility, humor and education – all three mixed in the right proportion in his speech. Every word and sentence that he uttered were filled with brilliance and beauty. People who heard the speech felt as if they were standing amidst a garden full of flowers or as though they were listening to the mellifluous singing of a great musician. The quality present in a great orator is not merely the variety in his usage of words and it is not just the force or profundity in employing words. Neither embellishments of language nor bodily gestures add much to a person’s oration. The predominant qualities are brilliance and beauty. Brilliance refers to throwing new light, which can kindle newer and newer thoughts in the listener’s mind. Beauty is what triggers waves of fresh emotions in the listener’s heart. Sastri’s speech was the perfect blend of bhāva-puṣṭi (bolstering emotions) and bhāva-pracodana (triggering new emotions).

Idiomatic Expression

Sastri’s speech was not direct or literal. It was full of oblique and idiomatic expressions. He would let his innermost thoughts and emotions out. Too many words go waste. An example comes to my mind.

Speaking about the abuse that (Sir Michael Francis) O'Dwyer caused to the people of Punjab, Sastri said the following:

“As for the part of Lord Chelmsford, not many words seem to be necessary. He must have been sufficiently punished by his own thoughts.” (occurs in English in the original text too)

“The punishment that his own mind hurls upon a noble and sensitive person is sufficient”.

This kind of oblique expression is considered to be the best in poetry.

To be continued...

This is the eighteenth part of the English translation of the Second essay in D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 6) – Halavaru Saarvajanikaru.