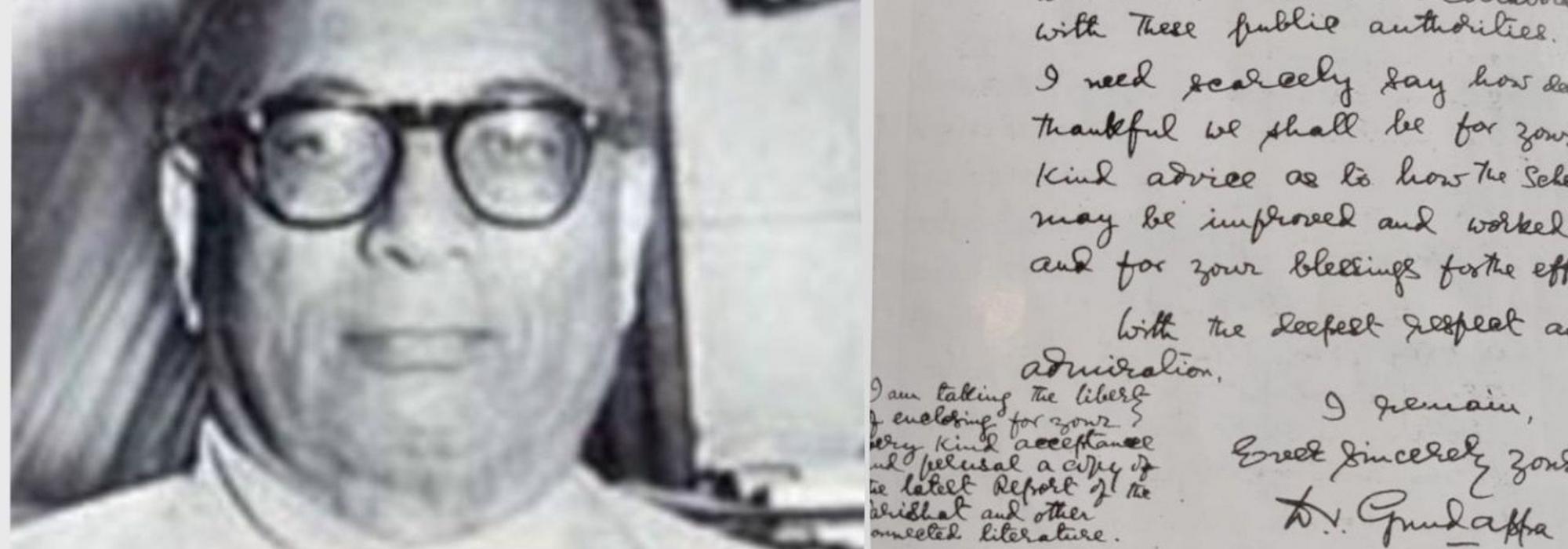

In a letter dated January 17, 1913, DVG outlined his future plans[1] to his father. It was titled Safe: A Personal Matter.

Following what Sri Ramadasappa had proposed in your presence while you were here, I am trying to start an independent English newspaper. He and other friends are helping me in this endeavor. I have also received the necessary permissions from the Government. So far so good. However, it is a money-intensive venture. I am seeking help in that regard as well. Both Sri Ramadasappa and Sri Narasimhamurthy are giving me great support. Still, if it is possible for you to help me with capital, this is the suitable time. Under these circumstances, it is difficult for me to send you money. The more capital we can raise personally, the better it will be. Please keep this matter highly confidential. Please do not share it with anybody, not even in your close circle. Of the total capital required, our investment must be substantial. If I don’t start this paper, I have no prospects for my future. I know that you won’t like it if I migrate to another state.

DVG estimated that the seed capital would roughly amount to ₹ 4,000. Accordingly, he decided to raise eighty hand loans of ₹ 50 each at an interest of five percent per annum. Explaining the necessity of starting his new paper, he wrote[2] to prospective investors as follows:

No one can gainsay that there is now in the Mysore State an urgent need for an independent newspaper to organize as also to articulate public opinion on all matters connected with the welfare of the people. The absence of open criticism and unbiased discussion of public affairs during the past few years has proved in an unmistakable manner the impending necessity for a strong press as an instrument of vigorous public life.

Fortunately, DVG’s efforts bore fruit and he was able to raise a tidy sum. The next step was perhaps the most difficult: obtaining the Government’s permission in a climate recently vitiated by the former Diwan Madhava Rao’s inexorable press gag. But in 1913, fortune had smiled on DVG because Sir M. Visvesvaraya was now the Diwan of Mysore.

The long, fruitful and cordial relationship that DVG and Sir M. Visvesvaraya shared is the stuff of legends and forms an eminent topic for an independent essay. In fact, DVG’s extraordinary profile of the titan running to hundred pages is perhaps the best tribute to him. While it can hardly be bettered, it is the most truthful and authentic raw material for the interested writer to flesh out their nuanced relationship. By all parameters, it is an ideal relationship between a selfless journalist and a passionate nation-builder endowed with indomitable integrity.

In earlier chapters, we have noted the chiseled role that Sir M. Visvesvaraya played in DVG’s life as a public personality. That was a much later development. DVG had first attracted Sir M. Visvesvaraya’s attention when the latter was the Chief Engineer of the Mysore State. In 1911, he took note of an article that DVG had written for the Madras-based monthly Indian Review. It was a brilliant analysis[3] of Diwan Rangacharlu’s administrative acumen. Sir M. Visvesvaraya contacted the editor, got DVG’s contact details and wrote a commendatory letter to the young journalist. That was the beginning of the aforementioned long relationship between the two eminences.

And now, two years later, DVG found himself meeting Diwan Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya at the iconic Balabrooie guest house in Bangalore seeking permission to start his independent newspaper venture. The Diwan said with a smile:

“May I know your age?”

“Twenty-four or five”

“So, you will criticize people twice your age, eh?”

“Not criticism, but assistance, help.”

“How will you help them?”

“Through an objective assessment of merits and flaws. If I inform the merits, your government will earn the goodwill of the people. If I point out the flaws, you will rectify them.”

Diwan M. Visvesvaraya laughed loudly when he heard this and said:

“I have no difficulty granting permission to people like you. What will you name your paper?”

“I haven’t decided it yet. Some friends have suggested Karnataka.”

“You can call it Progress, Forward, Development—something that indicates its purpose?”

“I shall discuss your suggestion with friends.”

The stage was set. The Diwan had himself signaled his approval. And then the proverbial devil of bureaucracy kicked in. DVG sent his application to the Secretary to the Government who in turn sent it to the Deputy Commissioner, Kumaraswamy Nayak. DVG was personally summoned and when he went there on time, Nayak was unavailable. This happened three more times after which DVG wrote a complaint to the Government. On the fourth occasion, Kumaraswamy Nayak met him. DVG observed[4] how he was immediately hostile. He did not extend the courtesy of asking DVG to be seated. He placed copies of Indian Review, Hindustan Review and other non-Mysore publications before DVG and began the interrogation:

“What is this? You’ve written in all these papers?”

DVG could barely contain his laughter. He said, “That is my profession.”

Deputy Commissioner Kumaraswamy asked him to leave and wrote his report: “He is a mere boy. Plus, he wears a Topi. He is not fit to discharge the serious responsibility of running a newspaper.”

The next chain-link in the bureaucratic rigmarole was the office of the Inspector General of Police headed by C. Srikanteshwara Iyer. When summoned, DVG stood before him with folded hands. This round of interrogation went as follows:

“Which is your native place?”

“Mulabagal. Kolar.”

“Where in Kolar?”

“Lawyer Sheshagiri Ayya is my grandfather.”

The Inspector General asked DVG to sit.

“So, you’re Sheshagiri Ayya’s grandson eh?”

Srikanteshwara Iyer’s father Subba Rao was posted as the Deputy Commissioner of Kolar and had great regard for DVG’s grandfather.

On March 12, 1913, the Mysore Government officially granted permission to DVG to start his newspaper venture, The Karnataka. On April 2, 1913, DVG gave a sworn statement before the District Magistrate affirming that he was the paper’s editor and owner and that it was printed at K.S. Krishna Iyer’s Irish Press located in Siddikatte, Bangalore.

The first issue of The Karnataka hit the stands on the same day, a Wednesday. The next issue was published on Saturday. The publication cycle was followed till the very end. The annual subscription to The Karnataka was eight rupees. Monthly subscription was fourteen Annas (roughly about 75 paisa). The following is a bird’s eye view of the paper:

· A total of twelve pages

· Four pages of advertisements

· A main editorial

· Letters to the editor

· Government news

· News about Bangalore and other important cities and towns

· Essays and op-eds

· The name of the editor was not published

Over time, a new column titled Views and Reviews was begun. This featured both scholarly essays and opinion pieces written by eminent people from various walks of life such as the Chief Secretary, Advocates, litterateurs, poets, and scholars. This is an eminent testimony to the kind of widespread goodwill that DVG had earned from such distinguished people at a young age. In no time, The Karnataka had emerged as the brightest new star emblazoned with honour, prestige and credibility in the annals of journalism in Karnataka.

In fact, the fruitful and highly productive journey of The Karnataka is a major chapter in the history of the modern Karnataka state itself, as we shall see. Today, when we read the archives of The Karnataka, we undergo a humbling experience of taking a profound guided tour of history. By itself, it remains DVG’s journalistic tour de force.

To be continued

Notes

[1] Virakta Rashtraka: D.R. Venkataramanan, Navakarnataka, Bangalore, 2019, pp 59-60

[2] Ibid p 60

[3] A comprehensive account of Diwan Rangacharlu later became part of the volume titled Mysorina Diwanarugalu, part of the complete works of DVG titled DVG Kruti Shreni, Government of Karnataka, 2013.

[4] D.V. Gundappa. Sankeerna, DVG Krutishreni, Vol 11, Government of Karnataka, p 235