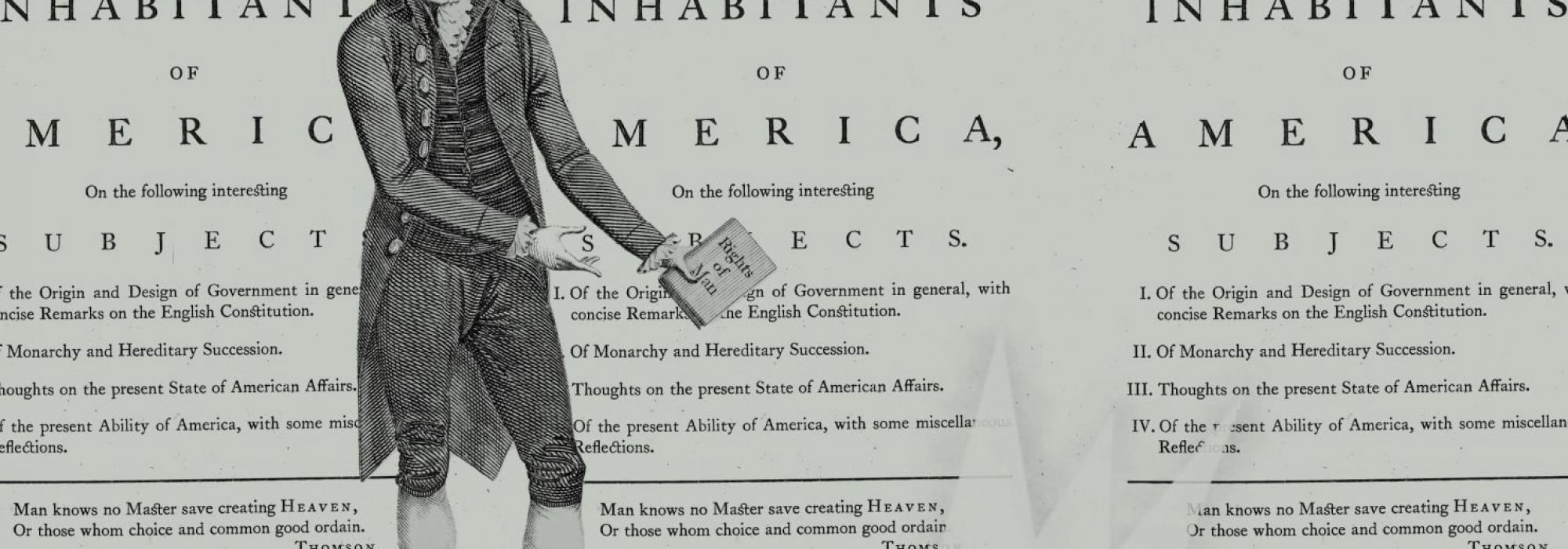

But at the doctrinal level, this consequence is the direct outcome of imposing the selfsame untested theory of freedom, democracy, liberty and related ideas fashioned in the West on an entire people who had fashioned their lives for more than three millennia based on a thoroughly different political, cultural and social inheritance. In other words, an all-encompassing and far-reaching change was thrust upon the entire population of the seventh largest country in the world without their consent. Bharatavarsha continues to pay the human cost of this change. This Britain-inspired Constitution was castigated[1] among others, by Thomas Paine—one of the founding fathers of the United States—in such acidic language as the “base remains of two ancient tyrannies.” Therefore, when the Constituent Assembly members averred[2] that this “Constitution as a whole, instead of being evolved from our life and reared from the bottom upwards is being imported from outside and built from above downwards,” this was what they meant.

Doubtless, those who fashioned such an imported Constitution had the best interests of the Indian people in mind but the end result was and remains a classic case of the road to hell being paved with good intentions.

And when we turn to DVG, we are astonished at how the deep profundity and pragmatism of his political philosophy was woefully ignored. This is truly tragic given that in DVG we find perhaps the optimum—if not ideal—blend of a political philosophy rooted in the native genius of a political order informed by and infused with spirituality and the mixing it with Western notions of individual freedom and democracy.

In his view, the theoretical and intellectual portion of politics was an examination and analysis of practical, everyday realities of national life lived through its people when he correctly, bluntly declares[3] that a “democracy is not a rule of saints and monks.” And further, that fundamental issues of politics must be pursued in the same spirit of philosophical inquiry[4] by “discarding personal attachments and prejudices.” The greater this sense of detachment, the sturdier will be our democracy. Adopting this method of inquiry also implies that there is no exclusive or only path[5] to attain the desired objective. In a way, this has a parallel in the Sanatana approach to attaining philosophical goals: through Jnana (inquiry), Dhyana (meditation), Japa (chanting), Tapas (penance), and other paths and methods.

In many cases, there is every possibility to attain a stated objective using [multiple] methods…Ultimately, it depends on the individual decision-maker’s erudition and wisdom to select the best course.

As noted in the earlier chapters, DVG never tires of emphasizing on the role, responsibility and accountability of the individual in public life because[6] “the subject-matter of politics is human nature.” And nowhere is the failure of the best laid plans more evident than in politics and public life: “in politics, the person who operates using mathematical formulae inhabits a world of illusions.”[7] This prophetic vision of DVG is timeless; in a sense it is akin to the proclamation of a Rishi when we observe the fact that in our own time, the overweening mantras of “data-driven” and “technology-driven” politics continue to cause havoc. Together, these phenomena have manipulated public opinion, diverted people’s attention away from real issues and adversely impacted elections, to list a few undesirable outcomes.

In our own time, and with the obvious benefit of hindsight, the following valid case can be made as far as India is concerned: the farther we travel down the path of western notions of democracy, the more Christianized will our outlook become. One can regard this from a different perspective: beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the destruction of the USSR, almost every single country to which the United States sought to “bring democracy” to has invariably been an Islamic theocracy. In turn, these countries have been the fiercest opponents of US-style democracy for a far more fundamental reason than their hatred of the US lifestyle and society. The cultural and civilizational inheritance of these Islamic nations instinctively detects the underlying Protestant-Christian nature of the United States and also recognizes the fact that America uses evangelism as one of the effective organs of its state and diplomatic policy. The clampdown and violence against Christian missionaries, destruction of Churches, etc that had occurred and continues to occur regularly in say Libya, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and even Turkey is a reflection of this fact.

Unfortunately, during the same timeframe, the record of Bharatavarsha in this regard has been really poor, to say the least. The Christianization of the urban Indian milieu and its vocabulary has been near-comprehensive. And in the present time, this is perhaps the most urgent reason to revisit and popularize DVG’s well-informed, reasoned and even stinging critique of the aforementioned Western notions and theories. These critiques shine illuminating light on and provide invaluable intellectual and philosophical fodder for anyone who is intent on rejuvenating the Bharatiya ethos in the realm of public life (broadly speaking). As DVG himself notes[8] elsewhere:

It was but natural for the Christian Padres who came to our country from alien lands to convert our people to their religion. And so they derided and mocked our dharma as the handiwork of the “Priestcraft” and our traditions as “superstition.” Imitating them, some of the highly educated folks among our own people regarded our traditional Vedic scholars with disdain and contempt. But there is indeed another perspective… no matter how far India progresses in the achievement of….material wealth, there will always be numerous other countries as competition. Indeed, I feel that our desire…to be equal to England, Germany, America, and Russia in material acquisitions…is itself an adventure. It’s our duty to attempt such things so let’s do it. But hoping that India alone will get the top spot is an argument of the extreme sort.

But the one field which doesn’t present any such competition is culture: specifically, the spiritual culture of India. This spiritual culture is the best and the finest of India’s wealth. If we don’t account for or neglect this spiritual culture, there’s no other area which India can take pride in. Forget pride, there is indeed no area where India can become useful to the world.

It will be most beneficial, useful and rewarding when we examine and study DVG’s political philosophy and critiques in this backdrop. Two other major factors are inseparable in this study: the Indian freedom struggle to which DVG arguably contributed in a more profound sense than most of the well-known leaders of his time, and his exposition of Dharma in the realm of public life.

Notes:

- Thomas Paine: Common Sense: Of the Origin and Design of Government in General, with Concise Remarks on the English Constitution

- D V Gundappa: Rajyashastra, Rajyanga—DVG Kruti Shreni: Volume 5 (Govt of Karnataka, 2013) Pp 150.

- Ibid Pp 176.

- Ibid Pg 177.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- D V Gundappa: Jnapaka Chitrashale: Vaidikadharma Sampradaayastharu: DVG Kruti Shreni: Volume 8: Nenapina Chitragalu – 2: (Govt of Karnataka, 2013). Upasamhara. Emphasis added.