Avadhānam is an ancient art/sport of India. It involves extempore creation of metrical verses on a variety of topics under myriad aesthetic constraints. It is a quintessential representative of that defining trait of all Indian classical arts – spontaneity. “Cittaikāgryam avadhānam,” “Avadhānam is the focusing of the mind” is its traditional definition. Any exercise in any art form requiring extensive concentration can borrow this term. Accordingly, we have Saṅgītāvadhānam (related to music), Sāhityāvadhānam (related to literature), Vedāvadhānam (related to chanting the Vedas with the right svaras” and the like. However, over time, Sāhityāvadhānam has become synonymous with the word “avadhānam” and hence we can examine that in detail. As with most things Indian, this also has its roots in Sanskrit.

Sanskrit and Versification

Even a superficial examination of Sanskrit and its corpus of literature will lead one to the conclusion that the language is tailor-made for poetry. So much so that even its most famous word-repository, the Amarakośa, is written down in metrical form. In classical Sanskrit literature, masters of prose made their name much after the masters of poetry, and they have proved to be an exception rather than the rule. So, in general, versification comes very naturally to Sanskrit. This is also reflected in the two hundred-plus meters seen in Sanskrit, of which some forty lend themselves to natural versification. This is a phenomenally high number and no language in the world can boast of anything close. This ease of versification led people to improvise and expand the frontiers of versification. Āśukavitā / extempore versification / versification-on-demand was an inevitable outcome it seems. The famous story about sage Vālmīki cursing the hunter in immaculate verse is a prime example of āśukavitā. Also, when tradition tells us that sage Vedavyāsa dictated his Mahābhāratam verses to a willing scribe in Gaṇapati, āśukavitā is what is implied. Vātsyāyana's Kāmasūtram lists āśukavitā amongst the cherished arts. Many other evidences can be summoned to show that āśukavitā was highly rated among the learned from a very long time. After the classical age, the quality of Sanskrit poetry noticeably declined and court poetry took centre-stage. Poets hardly came up with original themes or intricate characters. Instead, their efforts were devoted towards dazzling the nobility in court. To cut a long story short, form took precedence over content. This, however, enhanced the arsenal of the Sanskrit language even further. Patronizing courts were a perfect place to display one’s proficiency in language and versification. It must be in these fertile circumstances that āśukavitā discovered a framework in which to perform and prosper. This framework is what goes by the name of Avadhānam. As Sanskrit influenced and bred various regional languages, this propensity for āśukavitā was also transmitted to them. Haḻagannaḍa and Telugu are prime examples here. So, it comes as no surprise that the first direct evidence of Avadhānam comes from a Kannada source of the twelfth century CE. This inscription quotes a Sanskrit avadhāni by name Devaśarma[1]. Based on this, it can be safely assumed that Avadhānam was prevalent in Sanskrit much before. Over the centuries, Telugu managed to nurture and shepherd Avadhānam better than other languages. It is a tribute to the scholarly taste of Telugu people as well as the ease of versification in that language. In contrast, the evolution of Kannada was somewhat detrimental to classical versification. The guru-heavy nature of Haḻagannaḍa is a natural fit to classical meters. But the laghu-heavy nature of naḍugannaḍa and/or hosagannaḍa is not. This highlights the other important requirement for Avadhānam—the language should lend itself to a variety of non-monotonous classical meters. So, today, if anyone wants to perform an Avadhānam in Kannada, it is inevitable that he / she is proficient in haḻagannaḍa.

Philosophy of Avadhānam

As discussed earlier, Avadhānam is the framework in which āśukavitā metamorphoses into a performing art. In this framework, the performer is called avadhāni. The questioners who throw different challenges at the avadhāni are termed pṛcchakas. The most optimum format of Avadhānam—Aṣṭāvadhānam—involves eight pṛcchakas and an avadhāni. Every pṛcchaka throws his own challenge and the avadhāni has to respond to him, sometimes with partial verses and at other times with complete verses. For all the emphasis on āśukavitā so far, it is at best a necessary but not a sufficient condition for an Avadhānam. In other words, if one is not good at āśukavitā, it is a show-stopper; but merely being good at it does not guarantee an enjoyable Avadhānam. This is because, once something turns into a performing art, it becomes necessary that there are no uncomfortable pauses or dull moments on stage. This calls for the framework to include certain entertaining aspects, which play down the versification process of the avadhāni. This is where things like aprastutaprasaṅga, kāvyavācana, and saṅkhyābandha come in. With this background, the constituent sections or vibhāgas of a typical Avadhānam can be analyzed. The definition of these vibhāgas can be found elsewhere; here we only intend to analyze their nature and stature in an Avadhānam. A typical Aṣṭāvadhānam is performed over four rounds. Some vibhāgas demand only one quarter of a verse to be rendered in each round. Others demand an entire verse in each round. From a comprehension and appreciation perspective, they can be broadly studied under three different heads. It is possible that some of the vibhāgas straddle multiple heads. In that case, the classification below proceeds on which aspect gets higher weightage.

- Erudition Centric

- Niṣedhākṣarī

- Dattapadī

These vibhāgas are primarily based on erudition and scholarship. They tend to test the depth of the avadhāni’s vocabulary as well as his on-the-spot creativity in the language. Typically, they are dealt over four rounds with one pāda delivered in each round. Typically, in these vibhāgas, the avadhāni will need to call on his knowledge of the lesser known sandhis, kṛdantas and verb-forms to get around sticky situations he can potentially find himself in.

- Entertainment Centric

- Samasyāpūraṇa

- Āśukavitā

- Uddiṣṭākṣarī

- Saṅkhyābandha

These vibhāgas are primarily providers of entertainment. Samasyāpūraṇa involves solving riddles presented as metrical one-liners. Blasphemous and vulgar one-liners tend to keep the curiosity of an audience on the boil. The avadhāni has to, of course, sanitize the blasphemy or vulgarity therein, employing three more lines over three rounds to complete the verse. Āśukavitā is the most demanding vibhāga of all where the avadhāni has to instantly create a verse on a given topic in the specified meter. He creates one during every round of the Avadhānam. If the avadhāni can manage this well, he can take that confidence to romp through the other vibhāgas. This confidence would come especially handy in dealing with aprastutaprasaṅga, where the pṛcchaka can interject the avadhāni at will with any sort of question. Uddiṣṭākṣarī is a special case of āśukavitā, where the avadhāni is given a topic at the very beginning of the Avadhānam and soon after he is asked to provide the verse on a letter-by-letter basis as and when demanded. It looks deceptively simple but is hard to execute. Saṅkhyābandha is the only vibhāga that does not have anything to do with poetry. It is typically an exercise in completing a 5x5 magic square where the magic sum is provided beforehand and the pṛcchaka interjects the avadhāni at will to ask for the values of the different squares. Despite being the easiest of all vibhāgas, it seems to enjoy a disproportionately high wonder quotient with most lay audience.

- Oratory Centric

- Aprastutaprasaṅga

- Kāvyavācana

These vibhāgas primarily showcase the oratory of the avadhāni. Kāvyavācana serves the additional purpose of showcasing the connoisseur-side of the avadhāni’s personality. Over four rounds, he will have to identify and elaborate on four different verses drawn from different classics. A great avadhāni will use this to initiate the audience to the concerned work itself in a crisp way. He can also use the opportunity to delve into the style and substance of the concerned poet and evaluate him in an objective way. Aprastutaprasaṅga is the glue which holds all the vibhāgas of Avadhānam together and create an organic whole out of them. It is a test of the avadhāni’s ready-wit and willingness to engage on a variety of topics in a refreshing way. Depending upon the capabilities of the avadhāni and pṛcchaka, this vibhāga itself can scale high levels of entertaining scholarship. A willing avadhāni will also use this opportunity to introduce the audience to anecdotal verses and other cultural aspects spanning his range of study. In fact, these are the vibhāgas that elevate the art of Avadhānam from mere versification to something more enriching. It can be seen that these vibhāgas demand the avadhāni to be well-read on a variety of topics, from the mundane to the sublime.

- Adventure Centric

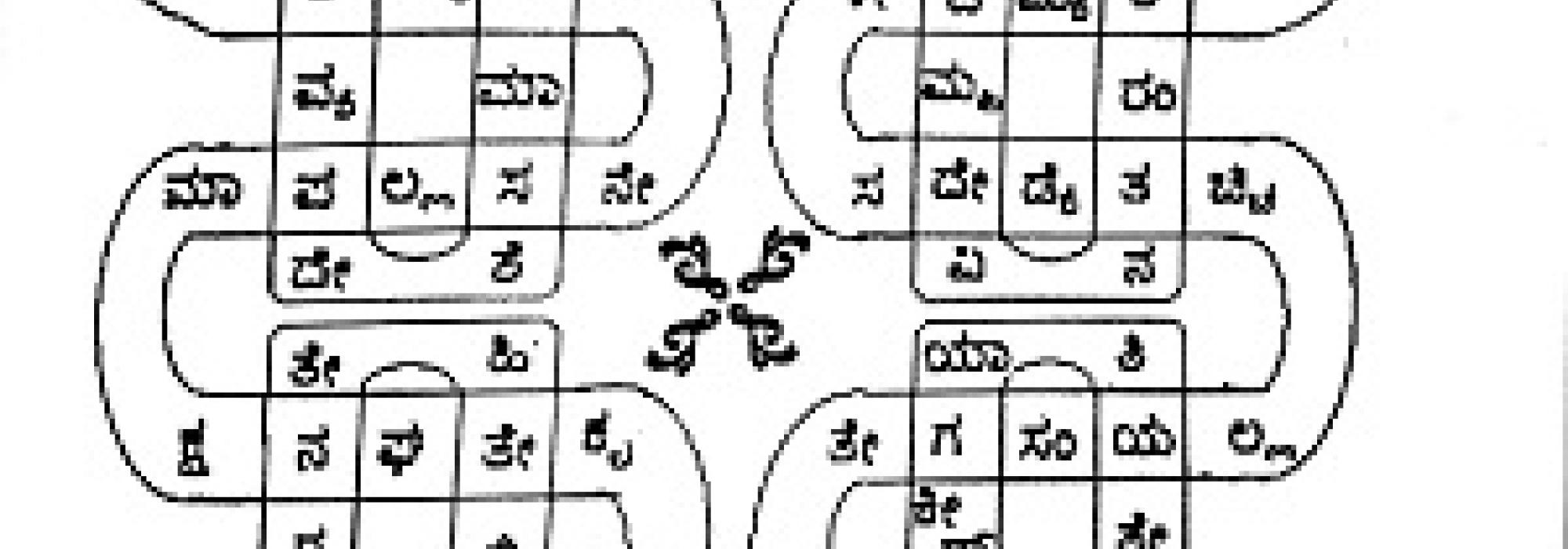

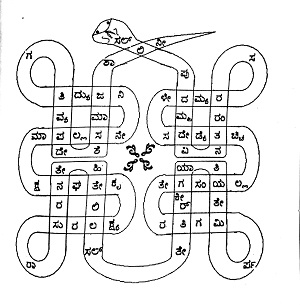

- Citrakāvya

- Nāṭakavācana

These vibhāgas push the limits of what is possible in an Avadhānam. Only an avadhāni par excellence can even start contemplating of performing these things on-stage. Śatāvadhāni Dr. R. Ganesh pioneered the introduction of these vibhāgas into Avadhānam. So far, he is peerless in the variety and complexity he has displayed in these vibhāgas as part of Avadhānam. Intolerably complex varieties of citrakāvya like sarvatobhadra, kuṇḍalita-nāgabandha, and cakrabandha have been handled by him on-stage. There have been instances when the pṛcchaka has asked him to versify in a hitherto unknown variety like anantarākṣarī, only for Dr. R. Ganesh to handle it like he has known it all along. Dr. R. Shankar, a reluctant avadhāni and an acknowledged master of citrakāvya, has also made it a part of the few Avadhānams he has performed. However, as far as nāṭakavācana is concerned, Śatāvadhāni Dr. R. Ganesh stands alone. It involves extempore translation of prose and verse from a section of a play into another language. This extempore translation is delivered in the way it would be done on stage, full with emotions and intonations as required. His translation of verses here is remarkable and is probably more complex than handling āśukavitā because the idea is not one’s own. These vibhāgas are not for the weak-hearted and it will not be held against an avadhāni if he does not include them to be part of his Avadhānam. In the light of the above discussions, it can be concluded that an Avadhānam is a judicious mix of versification, oratory and ready-wit. Mere versification without oratory or ready-wit will drive away any audience. Similarly, without good versification capabilities, the mind will not be free enough to exhibit either ready-wit or oratory and in turn the audience will be driven away yet again.

Footnotes

[1] Ref: Karnataka Inscriptions, volume 5, page 63.