Visvesvaraya’s Library

By the time (Sir M.) Visvesvaraya rose up to become a diwan, his acquaintance with Venkatanarappa had grown stronger. Visvesvaraya requested Venkatanarappa to help him put his personal collection of books in order. Venkatanaranappa carried out the task diligently and with great joy. Visvesvaraya was thrilled and he, as per his usual norm, intended to reward Venkatanaranappa with a material gift. This gave rise to a friendly dispute between the two. Venkatanaranappa was adamant saying that being a part of such an interesting task was itself rewarding and any other material recompense would only be an insult. Visvesvaraya argued that he never liked taking people’s assistance free of cost and as he was materially well-off, if he happened to engage any one without paying any remuneration, it would amount to theft. Finally, Visvesvaraya hinted that he would send a book of Venkatanaranappa’s liking in return of his favour. Soon after this, Visvesvaraya sent all the volumes of Scientific American along with a few other books as a token of gratitude to Venkatanaranappa.

Popularizing Science

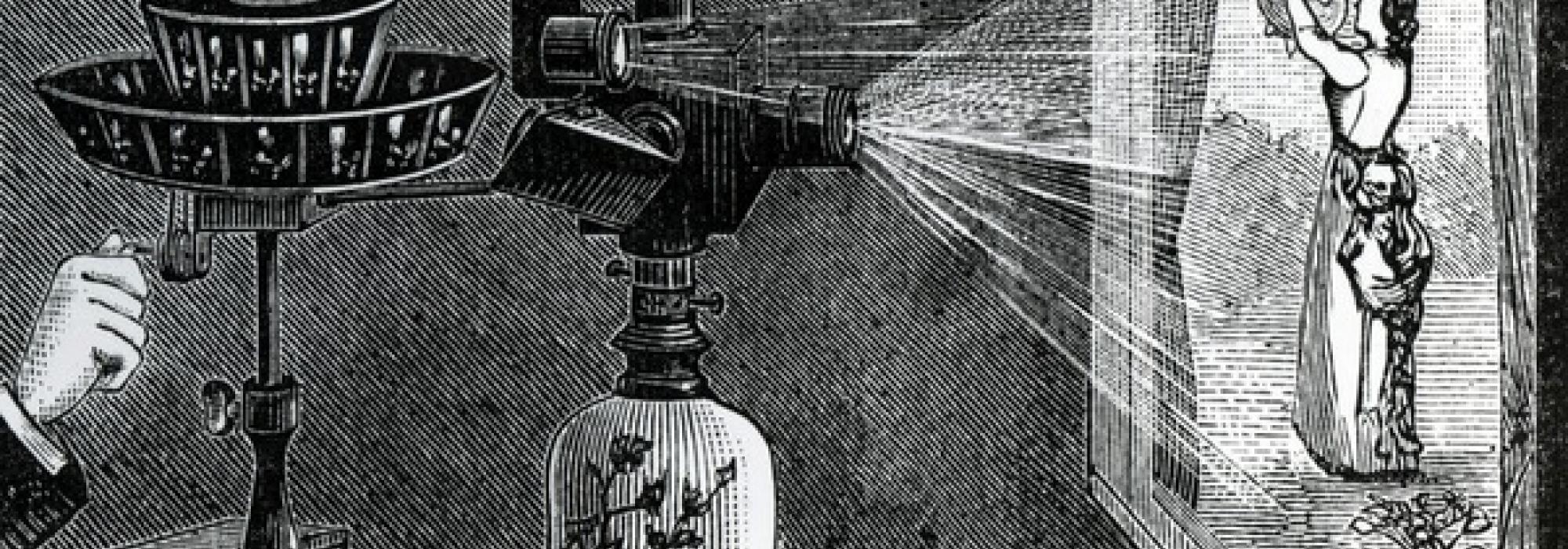

When these discussions were going on between Venkatanaranappa and Visvesvaraya, the topic of providing scientific education in the Mysore province was taken up. After a lot of deliberation, the two great minds decided that an organization for the propagation of science (‘vijñāna-pracāra-samiti’) was to be constituted. In addition, the organization was to run a monthly called ‘vijñāna’ (ವಿಜ್ಞಾನ). The inauguration of this organization took place in Janopakari Doddanna Shetty Hall. Visvesvaraya delivered the inaugural speech on the occasion. Venkatanaranappa spoke in Kannada on a few topics related to Phyiscs and showed pictures of Magic Lantern (a primitive type of image projector). Naganapuram Venkateshayyangar lectured on Astronomy. There were other important men who delivered talks in the lecture series. Y.K Ramachandraraya was one among them. He spoke on the architecture of houses.

On the first day of the lectures, the hall was so full that there was no place to even step into the hall. On the second day, the hall was not even half full and the third day was all the more disappointing. Yet, Venkatanaranappa’s enthusiasm did not come down. However, the eagerness of the speakers did not remain as it should have been. It was decided that we will re-attempt this endeavour from time to time and the topic was kept aside for the time being. My memory tells me that a couple of those lectures were published in the form of booklets.

English-Kannada Dictionary

During the days when the monthly, ‘Vijñāna’ was running, Venkatanaranappa realised the need for a good English-Kannada Dictionary. Even before that he often spoke about the necessity of such a dictionary. It was discovered that the Kannada dictionaries prepared by foreign scholars such as F. Ziegler were not that useful in practical usage. In scientific writing, a matter needs to be presented from different perspectives and various dimensions need to be addressed. The English language has naturally rendered itself for science. There were no Kannada equivalents for such scientific words in English. Venkatanaranappa had figured out through his practical experience that unless equivalent technical terms were coined in Kannada for these, we would not make tangible progress in the field of science.

We have mentioned elsewhere the reverence Diwan Sir Mirza Ismail had for Venkatanaranappa.

Venkatanaranappa voiced his thoughts on English-Kannada dictionary to Diwan Sir Mirza Ismail. The Diwan communicated the idea to the Maharaja of Mysore at an appropriate time and got his approval. The project which started in this manner culminated in the publication of the English Kannada dictionary by the Mysore University in 1946.

However, the directives given by the government in this regard were not easy to handle. Some colleagues of Mira Saheb were not enthusiastic about this project. Once, Mathens asked me – “What is the need for taking up this project afresh? Basel Mission Press has already brought out English-Kannada and Kannada-English dictionaries. They are in use since a long time. If they are not sufficient, we can request the Basel Mission to provide an expanded and edited version of the same and publish them. They are well aware of this kind of tasks. If the government co-operates, they might do it in a more efficient manner.”

In reply, I said – “I don’t think the contribution of such foreign institutes will be of much use in the current context. Only people who are constantly engaged in writing and speaking in Kannada in a scholarly manner are eligible in coining Kannada equivalents to those English terms. We have conversations with native Kannada speakers on a daily basis. We know how a matter needs to be presented for it to seep into the minds of the native speakers in an impactful manner. The foreigners don’t have this kind of exposure to the native soil. Those foreigners are not engaged in scientific writing either. Moreover, can we ever accept that we don’t have the potential or dedication in working for our own language?”

Final Decision

After this debate went on for a while, the government took a final call, according to which the Mysore University was to publish the English-Kannada dictionary. Bellave Venkatanaranappa was made the Editor in Chief. There were about seven to eight other members in the editorial board. I can very easily and wholeheartedly state that if not for Venkatanaranappa’s commitment and Sir Mirza Ismail’s constant trust and support, the dictionary wouldn’t have found the light of the day. After Venkatanaranappa passed away, M.R. Srinivasamurthy took up the post of the Editor in Chief.

The committee met once a month in the beginning. When they discovered that it would not help in the rapid progress of the work, they started meeting more often. The rule was that the meeting was to take place from twelve in the noon until five in the evening. However, the meeting hardly got over at five. Most of the times, the discussions went on until six or six-thirty in the evening.

Krishna Shastri’s Delicacies

I would like to quote a light incident here. At times, the committee met at eleven in the morning instead of at noon. The reason typically was the phalāhāra (snacks, delicacies) that was made available before the meeting. (Dr. A. R) Krishna Shastri had to travel from Mysore on the days that the committee met. The train from Mysore normally reached Bangalore at eleven. Even when Shastri resided in Bangalore, the committee waited for his arrival. Whenever he came, he brought along a packet of savouries such as āmboḍe and cakkuli and another packet of sweetmeats. In addition to this, he always brought seasonal fruits with him. B.M.Srikantaiah was strictly restricted from consuming sweets. Therefore, whenever he spotted jilebi or laḍḍu, he raised his hands and exclaimed - “This is not for us.”

“What will a little of this do to you? This sugar will eat up the salt and spice! Upon this, there is Krishna Shastri’s recommendation too. He knows medicine!” – as soon as one of us said so, our argument would find fruit in no time. Venkatanaranappa who would hear all this and would pleasantly smile without taking his eyes away from the book before him. Keeping time was very important to him – the meeting was to start at twelve at any cost!

To be continued...

This is the seventeenth essay in D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 3) – Sahityopasakaru. Thanks to Hari Ravikumar for his thorough review and Smt. Savithri Bharadwaj for her help in preparing the translation.