As in the other realms of his busy, productive and eventful life, DVG’s constant quest in journalism too, always sought the noble and the virtuous, thereby embodying the Rg Vedic dictum, ā no bhadrāḥ kratavo yantu viśvatah—may noble thoughts come to us from all directions. Consonant with this spirit, DVG displayed selfless profusion of generous praise towards British (in general, Western) papers and journalists that were independent and fair-minded. He had special regard for the following titans of journalism:

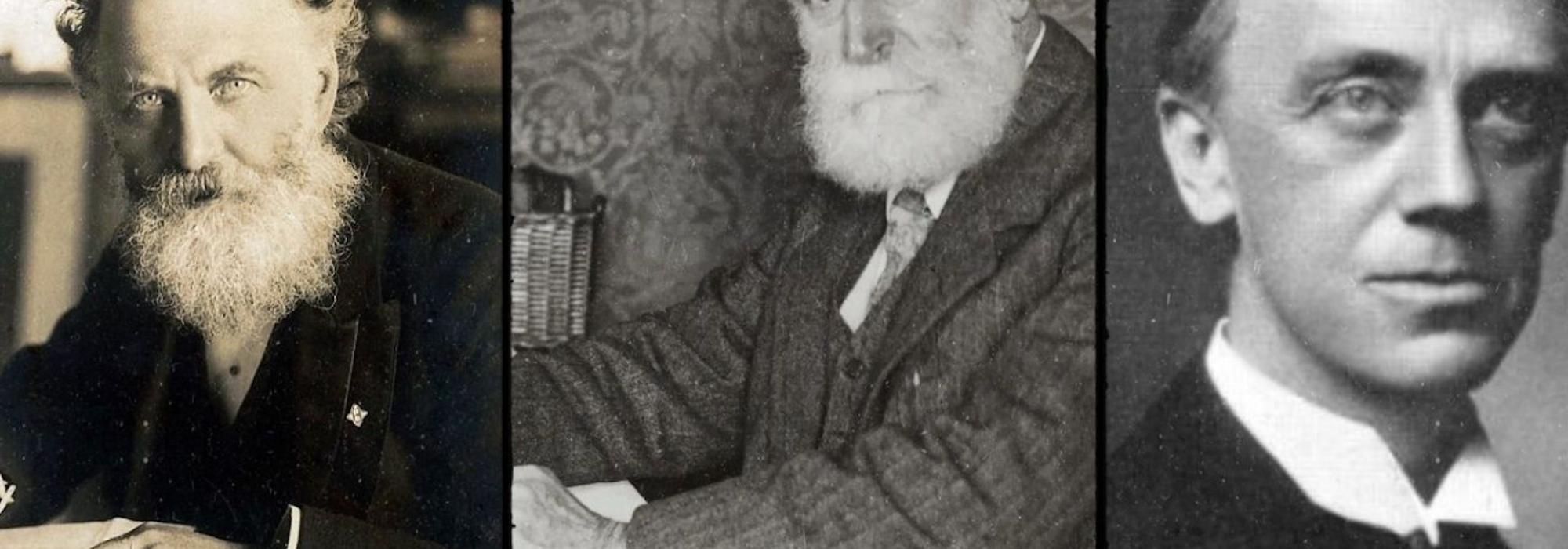

- The philosophical and fearless William Thomas Stead.

- The legendary C.P. Scott who he calls the “Maharshi” of journalism.

- The “father of journalism education,” Walter Williams, the acclaimed American journalist and editor.

In fact, DVG opens his Vruttapatrike with Scott’s enduring maxim: fact is sacred; comment is free. And he dedicates an entire chapter in the book to elucidate Walter Williams’ renowned, eightfold journalistic doctrine titled, The Journalist’s Creed.

However, DVG reserved his special reverence for W.T. Stead and wrote perhaps the best obituary to that doyen of journalism in The Karnataka. He acknowledges his lasting debt to Stead who “owes not a little of this writer’s education, both in general and journalistic, to the publications of Stead.” Indeed, this moving Ekalavyan tribute is fittingly titled, W.T. Stead: Our Journalistic Ancestor. Another measure of the devout esteem in which DVG held Stead is available in the very name that DVG gave to one of later publications: The Indian Review of Reviews. This was modelled after Stead’s acclaimed, Review of Reviews, in which “there was not a line that was dull, not a sentiment that was unworthy and not an observation that had not a message.” In what can be considered as perhaps the finest expositions on journalism and the media, DVG dips his pen in acid, searing the paper with a rare viscosity permeated by integrity:

There were many successful journalists in Stead’s time and there have been…many more since then. England has its journalistic colossus in Harmsworth; America in Hearst. They live for circulation, for big “business,” for the power of teasing the statesman and toying with States. They live to tell the people not what they ought to be told, but what they would like to be told. Sensation, slander, gossip, or whatever else may be wanted by the whim or passion of the hour, they would readily supply as the price of their popularity…They thrive as giants, having crushed or absorbed into themselves all smaller individualities endowed with talent still germinal and with independence still potential… journalism...[is] but a mode of seeking the fulfilment of…ideals…The true journalist, like the true poet and the true philosopher, has to extend his vision to the whole field of man’s life and thought…Stead was a journalist who was not a mere retailer of political news or fomenter of political irritations…one who was not unprepared to face unpopularity when justice necessitated it.

DVG’s own body of journalistic (and other literary) work is the accomplished reflection of giants like Stead and Scott, strictly speaking in the context of journalism. It is true that W.T. Stead “was not unprepared to face unpopularity when justice necessitated it,” and even went to jail for exposing the shocking depravity of teenaged prostitution in London.

However, in India, DVG had made a chronic acquaintance with unpopularity on recurrent occasions. As we have seen earlier, he staked his reputation and livelihood and earned the ire of the Government most notably during the 1928 Ganapati Clashes in Bangalore. This is apart from his numerous and sustained conflicts with Diwan Mirza Ismail and other powerful people.

But there is crucial difference that markedly sets DVG apart from his Dronacharyaesque Stead. In a way, Stead carried out his work from a relative position of strength: he was a newspaper editor in an England at the height of its colonial arrogance and his battles were criticisms against his country’s government, officials and so on. However, DVG as a subject of the same colonial England butted heads with the imperialist by fighting for India’s freedom. It was in this spirit that he acidly condemned the racist and imperialist writings against India by British papers, that is, against Stead’s counterparts in the press.

****

It is said that the writer’s conscience is the matrix of his art, and nowhere has this been more truthfully realized than in DVG’s journalistic career. As a journalist, DVG was not a chained observer of events but was both a herald and a director of our nationalist conscience. The entire gamut of this becomes clear when we note the philosophical, ethical and practical underpinnings[1] of his journalism. In his own words, this is as follows:

- There are no qualms in stating that the profession of journalism occupies an important place in our national life.

- It occupies a similar significance from the perspective of our ethical refinement.

- Therefore, the responsibility that it must shoulder is enormous.

- This responsibility has two facets: one, the dissemination of education; two, dissemination of ethics.

- The work of knowledge constantly demands the labours of study and scholarship. It is never enough.

- The realm of ethics demands intellectual objectivity and judicious caution.

- Nobody can honestly say that he is fully endowed with this wealth of scholarship, intellectual objectivity and judiciousness to separate right from wrong.

- It is purely a matter of luck to expect worldly rewards for all these labours.

- Like in other spheres, there are ample temptations for satisfying one’s greed and to stray from the righteous path in journalism.

- The chances of a journalist falling from high standards are greater owing to disappointments of not receiving rewards or fame.

This is timeless advice by any standard. And in DVG’s view, the editor’s responsibility is the greater. Thus, the[2] “editor must have a philosophical outlook and must objectively investigate any issue with a quest for truth. This disposition of seeking the truth is the moral and ethical capital of a newspaper.”

Neither does DVG ignore the other areas: his expositions on the role of the citizen vis a vis the press, the Government’s relationship with the press, the business face of journalism and his conception of an ideal newspaper are all equally worth their weight in gold.

To be continued

Notes

[1] D.V. Gundappa. Sankeerna, DVG Krutishreni, Vol 11, Government of Karnataka, p 213

[2] Ibid. p 241, Italicised.