1. Inner Vision

Five or six days after the [Kannaḍa Sāhitya] Pariṣat was established (in 1915), one day at about three in the afternoon, two eminent people came to my workplace. At that time, I was running the Karṇāṭaka, an English newspaper that was published twice a week. The newspaper office was in Gundopanth’s building on Gundopanth Road in Siddikatte [Today’s Krishna Rajendra Market]. The Karṇāṭaka office was on the top floor. K S Krishna Iyer’s Irish Press occupied the ground floor of the building.

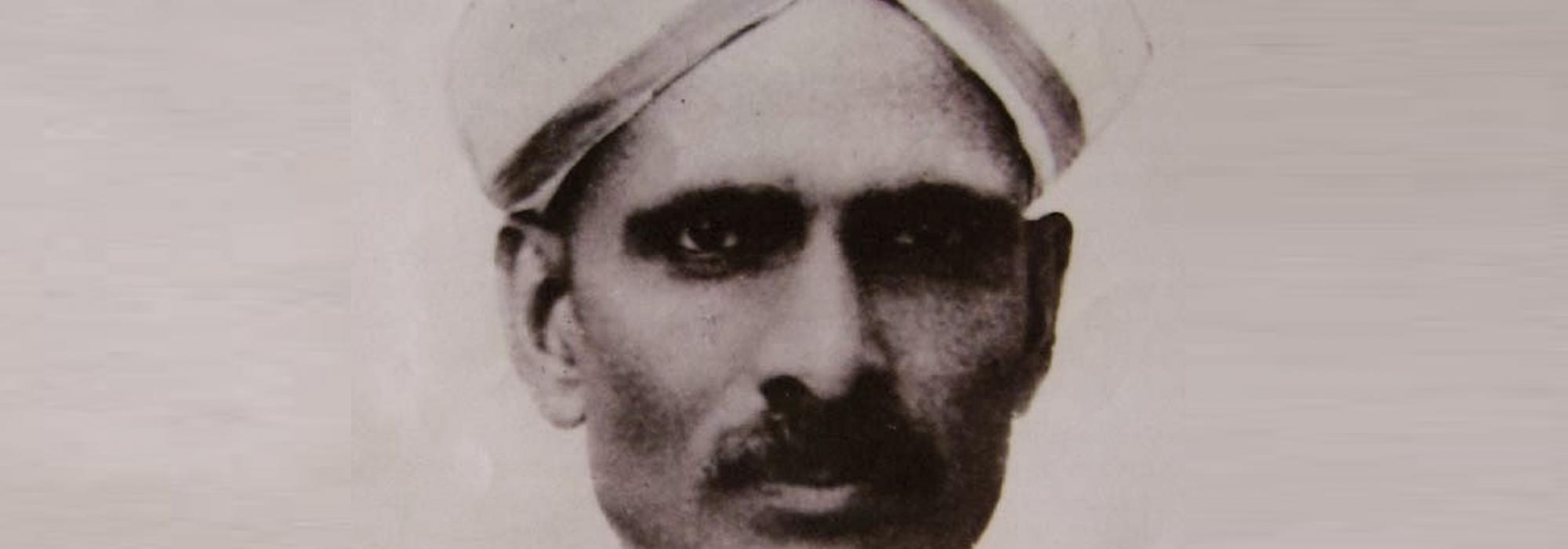

Of the two visitors, one was tall and lean. I recollect that he wore a shirt, an open-collared coat, and a necktie. He sported a pointed turban in the Punjabi-style. One end of the turban hung on his left shoulder. The other end was at the top of the head like a crest. He was a man with swagger. That was T S Venkannayya.

The other visitor was neither tall nor short; neither skinny nor hefty. He wore a Mysore-style traditional kaccè-pañcè[1] along with a close-collared coat and sported a turban with a golden border. That was A R Krishna Shastri.

I addressed them both with the questions – “Who are you? What brings you here?”

Krishna Shastri replied, “We’ve come from the Cantonment. We’re dedicated to the cause of Kannada. We have come to discuss with you regarding this.”

The discussions began. Krishna Shastri said, “Sir, the people who founded the Pariṣat are all old and ‘prestigious.’ And you have joined hands with them! What work can they do? If the Pariṣat doesn’t have people who will work, what’s the use?”

I said, “To begin any great endeavour, don’t we first need some money? The government has come forward to sponsor it. This is due to the generosity of Dewan Visvesvaraya. He trusts H V Nanjundayya to get the work done. The key government functionaries are well-acquainted with all these elderly folk. Further, these elders have gained the respect of the people as well. Why should we disassociate with them? How can one say that Karpura Srinivasa Rao or Dr. Achyuta Rao do not hold Kannada in high esteem? The organisation gets prestige because of them.”

Krishna Shastri said, “All that may be true sir, but what about work? Who among them will get their hands dirty? Will work proceed with such grey-haired people on board?”

“If that’s the case, what should I be doing in your opinion?”

“Youth must be brought in for this work.”

I asked, “Is that something that can be achieved by me?”

Krishna Shastri replied, “If you provide support, we shall do that work. You are someone of our age, and you’ve got caught with those senior citizens!”

“I haven’t gone behind them. They said, ‘Come, let us do some good work,’ and so I went. Now, if you ask me to join you, I’m ready for that as well.”

Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha

Within a couple of months of this meeting, the Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha of Central College, Bangalore was started. That was born not as a competitor to the Pariṣat but to merely complement its effort and for completeness. Prof. B Venkatanaranappa, who was a prominent member of the Pariṣat was the head of the Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha. For many years, the activities of the Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha were more successful as compared to those undertaken by the Pariṣat. Time and again, lectures, kāvya-vācanas[2], and santoṣa-kūṭas (friendly get-togethers) were organised. The periodical Prabuddha Karṇāṭaka[3] consistently carried valuable essays and gained renown over time.

Great litterateurs and scholars of Kannada such as R Narasimhacharya, C Vasudevayya, Benegal Rama Rao, H Lingaraja Urs, and others participated in the annual celebrations of the Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha and enhanced its stature.

Santoṣa-kūṭas

Among the activities of the Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha of Central College, santoṣa-kūṭas [friendly gatherings] were a regular affair and we would get to participate in them. It is my experience that such events are extremely important when young people are involved. This opinion holds good even in the light of my experience at the Kannaḍa Sāhitya Pariṣat.

A R Krishna Shastri was largely responsible in organising the santoṣa-kūṭas of the Karṇāṭaka Saṅgha. Snacks and savouries would be arranged to his liking. Everyone approved of his taste and praised his selection. Good kosambari, well-made pānaka, well-chosen seasonal fruits – these were the things he insisted upon. He would personally go to the market and buy the best ingredients; the preparations of all the dishes would be personally supervised by him. He would himself check the recipes and the proportions of the ingredients and guide the chefs.

Krishna Shastri never felt any activity of the Saṅgha was beneath him. From holding a broom and sweeping the floor to cleaning the dust off the books in the library to shifting furniture—chairs and tables—for a meeting, there was no task that he didn’t take up. The seriousness he exhibited towards grammar and literary research was unchanged when it came to menial work as well; he had the same intensity of dedication even when it came to chores. That is the reason his arrangement of snacks and drinks were such a success. Each item would excel its predecessor.

In these matters, Venkannayya’s role was different. Krishna Shastri was the type who would do the work, while Venkannayya was one who would get the work done. The moong dal kosambari would be getting prepared and at that time, Venkannayya would come there and say, “Wonderful! This is going to be great! If some grated raw mango falls on this, the taste will be delectable.” Those who heard him would do his bidding at once. If he came to know that āmboḍè is being prepared, he’d go there and say, “Fantastic! Right in the middle, you’ll add a bit of raw ginger, won’t you?” There were people who would immediately pay heed to his advice. In the avarekāyi [broad beans] season, uppiṭṭu is a wonderful delicacy to prepare. “If some pepper is added while making the uppiṭṭu, hand-stuffed, and steamed, it will be a royal treat!” It would be implemented in exactly that manner. Venkannayya and Krishna Shastri had many such contrasting traits. Venkannayya would get the work done by speaking in a friendly, gentle, soft-toned, and enchanting manner. Krishna Shastri was sweet in matters of food and hospitality but was sharp and firm when it came to speech.

They complemented each other. But in what aspect? In literary endeavours, something that was dear to both their hearts.

To be continued.

This is the first part of an eight-part English translation of Chapters 23 and 24 of D V Gundappa’s Jnapakachitrashaale – Vol. 3 – Sahityopasakaru.

Footnotes

[1] Dhoti worn in a manner that resembles trousers.

[2] Recitation of classical poetry, typically set to classical rāgas, followed by a scholarly exposition of the same.

[3] A R Krishna Shastri started the Prabuddha Karṇāṭaka periodical in 1918 and worked as its editor for many years.