orvane niluve nīnutkaṭakṣaṇagaḻali ।

dharmasaṃkaṭagaḻali, jīvasamaradali ।।

nirvāṇadīkṣeyali, niryāṇaghaṭṭadali ।

nirmitraniralu kali – maṃkutimma ।। 689 ।।You will be standing alone in all the intense and turbulent moments of your life,

When faced with moral dilemma, fighting the battle of life,

During the moment of self-realization, and in death.

Learn to be friendless - Mankutimma

***

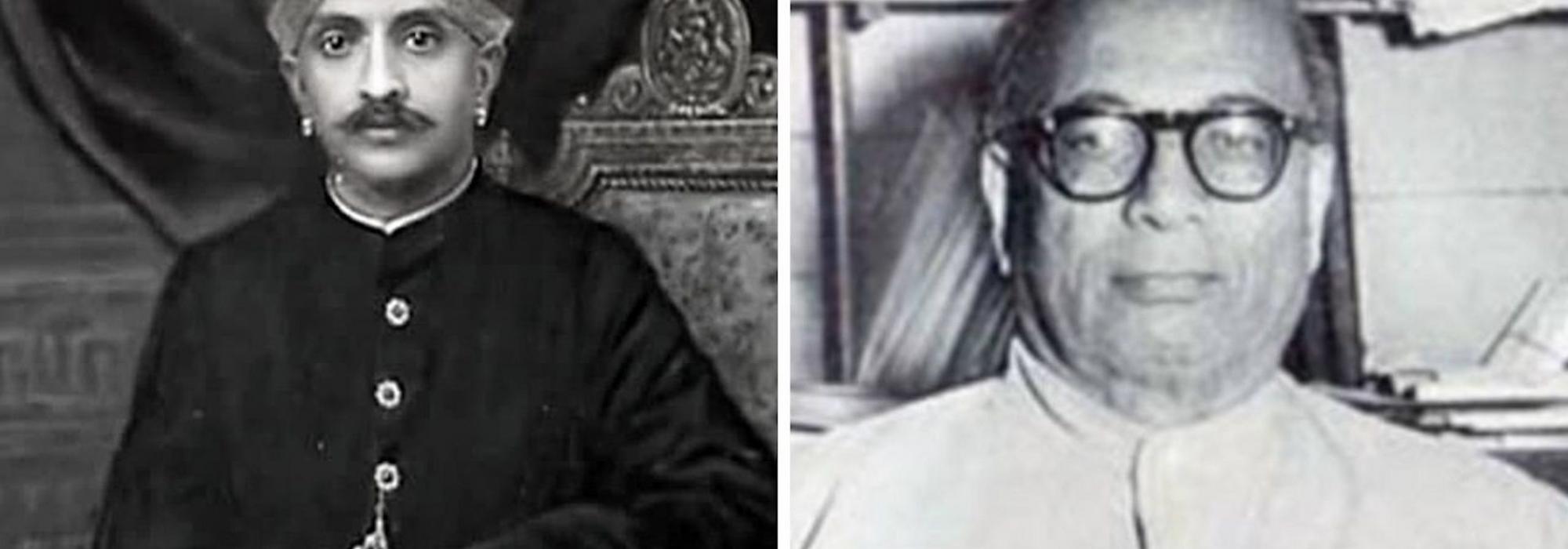

The Reforms Committee constituted by the Mysore Government was headed by Sri K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar. The Congress party nominees who were members to the Committee gradually stopped attending its proceedings after January 1939, less than a year after it was constituted. Among the major reasons for this development was a divergence of values and a lack of understanding the full import of Responsible Government in practice. Sri Chengalraya Reddy, a prominent Congressman said that he was in no hurry for full Responsible Government in Mysore. However, he would be satisfied if the Mysore Government would implement all the “constructive activities” that (Congress) Responsible Governments were undertaking in the six or seven states where they were in Government. Chengalaraya Reddy would become the Chief Minister of the Mysore State after India attained independence.

However, DVG had a more nuanced and an all-encompassing perspective towards this cause so dear to him. He likened Responsible Government to climbing a ladder and all the dangers that accompany it: “A slight misstep might bring us down to a rung far lower than where we had been when we began climbing.” As we have seen on numerous occasions in the preceding sections, DVG tirelessly emphasized on the necessity for a full, truthful, and thorough self-training for Government. Among other things, Responsible Government was one which could anticipate the aspirations of the people in advance and was in fact the very vehicle for realizing these aspirations. In this context, DVG, in his editorials, newspaper columns and speeches, cited and upheld the ideals of Diwan Rangacharlu who seeded the Mysore Representative Assembly. In his speech to the Reforms Committee, DVG observed with some causticity that, “although there has been tremendous political growth in the Mysore State, this ideal of Diwan Rangacharlu has not been realized till date.”

That was the beginning of a chain of petty politicking which ended in disappointment as far as DVG was concerned.

The reason was not far to seek. On one side the Mysore Government’s nominees feared that the kind of Responsible Government DVG was advocating would dilute and “bind the Maharaja’s hands from functioning with discretion.” On the other side, the Congress nominees were unwilling to undergo the kind of rigorous self-training that DVG had in mind. The same Congress Party which had repeatedly agitated for and publicly declared that “Responsible Government is our only goal” suddenly deserted DVG in the very Committee that was set up for achieving this goal. DVG was isolated and his position was akin to what he describes[1] in his Mankutimmana Kagga as, “You stand alone in the most intense and the most trying moments in life.” However, DVG did not allow his disappointment to consume him. As always, he took the honourable route. Indeed, the conviction he expressed in the March 1938 letter to Mirza Ismail had proven to be unambiguously correct. At 9 PM, on 16 March 1939, he reiterated the same conviction in another letter:

As you know so well, I have cherished and advocated the ideal of Responsible Government for over twenty-two years now. I have spoken and written…in favour of it in public on every available occasion; and it will surely be doing violence to my own conscience if at this stage of my life I swallowed the conviction of a lifetime…On [this]… I can make no compromise…There are some things which everyone of us holds to be sacred and unassailable and beyond the province of bargaining. Responsible Government issue to me is such a thing. That being so, if the committee will not agree to recommend Responsible Government as a goal at least I can have no place in it.

The letter had the intended effect. The Committee decided that DVG’s arguments were not only persuasive but profound. Several more rounds of discussions took place and the Committee submitted its final report comprising twelve major recommendations authored by DVG. It was a tour de force that struck an extraordinary balance between the ideals, belief systems, traditions and customs prevailing in Mysore from the ancient times and the aspirations of the advocates of Responsible Government. It is also noteworthy that DVG made it a point to specifically include the prohibition of separate electorates for Muslims and Christians. Likewise, DVG also ensured that he upheld the primacy and dignity of the Mysore Maharaja by mentioning that the proposed reforms had to be carried out under his guidance, wisdom, and protection.

After the report was ready, DVG wrote a monograph anticipating the objections to the report. Its concluding paragraph is truly brilliant.

To see clearly into the future farther than a few paces in front of him is given to no man. In which exact year of grace Responsible Government will…be established in a perfect form in Mysore and what its distinct features will be questions that need to be asked, for the answer is obvious that fulfilment will be largely in accordance with the good sense and capacity of the seekers.

The last line is yet again consonant with his lifelong mantra of the qualifications required for people wishing to run a Government.

***

The Mysore Maharaja passed a royal order on 6 November 1939 in response to the Reforms Committee Report submitted on 31 August. It was a cruel blow and a complete mockery of the Report. DVG wasted no time to condemn it. In his words, while the Report sought for a gradual and systematic devolution of Government powers to the Representative Assembly, what the Government order gave was greater interference. He concludes, “What is now needed is a recasting of the relationship between Government and the people from a position of benefactor-seeker to that of Rights and Duties. This Government Hukum (Order) is so disappointing that it appears to mock the very notion of democracy.”

A barrage of newspaper articles, editorials and columns followed. Prominent editors like Tirumale Tatacharya Sharma and others relentlessly castigated the Mysore Government for its callous attitude. However, the Government was unmoved. On this side, DVG and other public figures of his stature embarked on a campaign of educating people in democracy, self-government and Responsible Government. Monographs, books, and essays encouraged young men and women from all walks of life to get a fundamental grounding in political education.

It can be argued that DVG suffered a deep, personal wound by the latest Government Hukum. He felt defrauded at what can be interpreted as political chicanery on the part of Diwan Mirza Ismail who outwardly endorsed Responsible Government but did the exact opposite in practice.

Despite such yawning differences, DVG’s faith, respect, and integrity towards the Mysore State and its royal family was abiding. A great testimony to this is his superb, near-poetic tribute on the death of Krishna Raja Wodeyar IV in August 1940. Writing in the August issue of Triveni journal, DVG described the Wodeyar as,

…his politics had for its basis a certain upward looking disposition of the soul. He was forever on a quest of Dharma…The late Maharaja was a lover of great solitudes and great silences…He was such a one among princes as might have been singled out by Plato for approbation. He belongs to the company of Ashoka and Aurelius, with the splendor of the crown made mellow by the wrinkles on the brow.

Indeed, circa 1940 was a pivotal year in DVG’s life. As he had noted in his letter, such an extraordinarily long stint in public life had made him a sick man who had realized at least one fundamental truth about this sort of life. This truth became a maxim of sorts for him and Cardinal Newman’s brilliant sermon[2] had delivered it to him.

We are not born for ourselves, but for our kind, for our neighbour, for our country… we owe much to those who devote themselves to public life…in public life a man of elevated mind does not make his own self tell upon others simply and entirely. He must act with other men; he cannot select his objects or pursue them by means unadulterated by the methods…of men less elevated than his own. He can only do what he feels to be the second best.

In hindsight, Newman’s “second best” was imprinted in DVG’s mind. He echoes this sentiment in his Rajyashastra in his inimitable fashion:

The person who sets out to achieve his own objective no matter how noble it is, does not understand the nature of politics. He is unaware of the difficulties and dangers therein. These dangers lie in hiding. However, an accomplished politician who intends to accomplish good things knows these dangers and he keeps working to achieve the best that is available within his reach. If this best is second rate, he will be content to accomplish just that. As the political expert Morley said, ‘politics is a long series of the second best.’

Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV’s death and DVG’s disappointment with the Mysore Government’s mocking order was the dusk on DVG’s public life. He had made up his mind. In 1940, DVG’s term as the Member of the Mysore Legislative Council came to an end and he refused to contest again. The next year, he also vacated the Mysore University seat and wrote a public letter to his voters giving details of his honest service to them for six years. It was a heartfelt and moving expression of gratitude for the faith they had reposed in them.

That was the end of his public life, to which his epitaph reads as follows: “After that, I had no direct contact or association with the Government in any form. From then on, I am a mere witness—a faraway witness.”

Postscript

DVG’s much-cherished Responsible Government ultimately came in 1948 and when it did come, it was a deformed infant, a premature birth midwifed by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

To be continued

Notes

[1] orvane niluve nīnutkaṭakṣaṇagaḻali ।

dharmasaṃkaṭagaḻali, jīvasamaradali ।।

nirvāṇadīkṣeyali, niryāṇaghaṭṭadali ।

nirmitraniralu kali – maṃkutimma ।। 689 ।।

[2] The National Institute of Newman Studies: http://www.newmanreader.org/