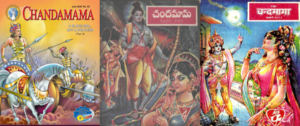

The name ‘Chandamama’ itself is so sweet. For all children, the Moon is like their lovely maternal uncle. This attractive word, although appears to be in the language of children, is originally a Sanskrit word. It is well-known that the Moon is commonly called ‘Chanda’ and someone close is often called ‘Mama’ in Sanskrit. It is seen that the same word is used in Kannada, Telugu, Hindi, and so on. This publication, titled ‘Chandamama’ in the Sanskrit version was called ‘Ambulimama’ in Tamil and Sinhalese and ‘Chandoba’ in Marathi. Once a grammarian had interpreted the meaning of ‘Chandamama’ as ‘candasya māṃ lakṣmīṃ mātīti candamāmā’ – ‘that which can certify (or measure) the splendour of the moon.’ Let that be; now we will proceed towards Chandamama’s world of stories. Chandamama’s stories fall into diverse categories: Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, Bhāgavata, Devībhāgavata, Manvantara stories, legends of Gods-Sages-Kings, thousands of stories from the world of Purāṇas. The main source of my initial knowledge of Purāṇas was Chandamama. Stories chosen from the Vedic Saṃhitās, Brāhmaṇas, Āraṇyakas, and Upaniṣads are also a part of this publication. There are several attractive stories on the oral history of pilgrimage centres. The language of all these stories was earnest and simple; their strength lay in their details and thoughts. In the Mahābhārata serial, what was particularly disappointing was how they sped up the segment from the Droṇaparva until the Śānti-Anuśāsanaparvas, which are elaborated a great deal in the original. There was no dearth of excellent serials that were beautiful and filled with imagination. We can start with the beautiful collection of novels like Durgeś-nandinī and Navāb-nandinī in Bengali. Serials like the story of twin children, Dhūmaketu (comet), Makara-devate (crocodile deity), Marāḻa-dvīpa (island of corals), Mūvaru Māntrikaru (three sorcerers), Rakkasakoḻḻa (valley of demons), Pātāḻadurga (nether-world fort) Kañcina Koṭe (bronze fort), and so on were famous. When I began reading Chandamama, ‘Śitilālaya’ was the serial that was being published. I was so enthralled by the main characters in that story – Śikhimukhi, Vikramakesari, the priest from Śitilālaya, Nagamalli, and Śivāla – that I found them far better than reality. This story had absolutely no superhuman elements and spoke about several exciting topics such as the crocodiles of the Brahmaputra river, the dense jungles of Assam, canals, ibhyas (possessor of many attendants), nagas, aghoris, and the peculiarities of the city of Kamakhya. The illustrations of ‘Chitra’ that used to fill life into these stories, created such intimacy that, to me, the whole story played out like a movie. I have often discussed with my elder brother as to why our Indian film industries never got around to making such stories into movies. ‘Śīlaratha’ and ‘Yakṣaparvatha’ that came after Śitilālaya were not bad but they did not match the quality of the previous serials. By the time the ‘Māyāsarovara’ serial was being published, the quality had come down. After that, the illustrator Chitra disappeared. The beauty of Chandamama was eclipsed. Stories translated from the Greek poems of Iliad (as Bhuvanasundarī) and Odyssey (as Rūpadhārana Yātregaḻu) emerged in all their beauty. The pictures drawn by Chitra for these stories have become a good representation of Greek culture. The back cover with a glimpse of these was also drawn by Chitra. Who was the creator of all these interesting serials – I don’t know. Must have been Chandamama’s editorial board. I always offer my appreciation and adoration to them.

The Bhetāḻa Stories are one among Chandamama’s specialities. The original Bhetāḻa collection (Bhetāḻapañcaviṃśati) had only twenty-five stories. It was Chandamama’s gift to the readers to add hundreds of imaginary stories to the original twenty-five. If someone were to collect these stories and polish them a bit, that will become an anthology of ‘Modern Tales of Vetala.’ In the beginning, I could not comprehend these stories. Later I started enjoying them a great deal. It is said that the popular Telugu novelist Yandamoori Veerendranath himself for the first time wrote a Bhetāḻa story and sent it to the Chandamama editor Kutumba Rao. Until then, imaginary Bhetāḻa stories were created by the editors. The story ‘Rāji’ that was created by the young Yandamoori appealed to Kutumba Rao and it is said that he predicted that this writer will become famous in the future. This story is truly full of rasa. The morals of Bhetāḻa stories lie in the subtlety of their logic, vision of dharma and karma, and in the incisive examination of human life. The Paropakāri (lit. ‘one who helps others’) Pāpaṇṇa Series is another feather in the cap of Chandamama. Perhaps there’s no one who does not like these stories. While Shankar was the artist for the Bhetāḻa stories, Chitra was designated for the Paropakāri Pāpaṇṇa stories. Pāpaṇṇa’s integrity, simplicity, and innocence combined with the pressure of circumstances subject him to loss and difficulties. In the end, they highlight his dignity and greatness. These unforgettable stories remain etched in memory. These stories have offered great support to me in holding on firmly to my beliefs and values of goodness. Pāpaṇṇa’s hairstyle was unforgettable. The illustration of Pāpaṇṇa’s mannerisms and postures were unique, and it changed from his youth till his middle age. The person who wrote these stories is only known by the pen name ‘Sunanda.’ In the days that followed, the stories that ‘Vasundhara’ wrote were also attractive. It is worth noting that although M K Ishwara Rao’s stories had the banality of modern-day social life, it was ingenious to present it in the framework of a Chandamama story. After all, miracles and magic are always captivating. The Tāttayya stories were also interesting. Here the setting was friendly and intimate. Further, the specialty of single-page stories is also worth describing. Truly writing such stories is a difficult task. Chandamama has given many beautiful and astonishing stories of evil spirits, ghosts, and demons. It has also given us tales of the storytelling granny, princes and princesses, wise men, and sorcerers. It’s the fruit of our good deeds that nobody created a fuss about it being a reactionary magazine promoting blind beliefs and useless traditions. At any rate, such accusations cannot be made about Chandamama. A beautiful and apt example for this is the hundreds of stories that the magician A C Sarkar used to write. The form and flavour that these stories took by using the techniques of magic in a way that resulted in universal welfare and happiness of the people are unforgettable. Stories of many dimensions – the world of little children, amazing stories of kings, the troubles of poor farmers, the plight of the poor, the mischief of merchants, the deception of thieves, the life of brāhmaṇas, the life of birds and animals – appear beautifully in Chandamama. The Pañcatantra ran as a serial for decades. To my knowledge this was far more interesting, simpler, more elegant, more lucid, and far more detailed than any other translation of the Pañcatantra. The basic beauty of this magnum-opus was encapsulated there.

Respect and curiosity for Islamic traditions, the ways of life of Arabian muslims, and their fine taste were roused in me by Chandamama. This was by means of the Arabian Nights Series printed in the monthly. I particularly remember Alibaba and the Forty Thieves, The Travels of Sindbad, stories of Caliph Haroon al Rashid, Aladdin and the Magic Lamp, The Deceitful Old Woman (the Dilaila story), stories about the suffering of good people, The One Day Sultan, The Unmeltable Wealth, as well as innumerable big and small serial stories due to their Islamic-Arabic scent, Chitra’s sketches, the in-built miracles, the sense of humanity and heartiness. What’s more, Chandamama’s stories have given my life light, joy, and understanding. Throughout my life, the sweet sensations from reading Chandamama have remained and grown inside me. What is the secret of the success of Chandamama’s stories? Is it their simplicity or succinctness? Or is it the astonishingly beautiful imagery and narrative? If not, is it romantic fantasy, which the human mind always wants in some quantity, to run away from reality? Which one? [These stories are not fantasy is the sense of the ignoring the world. Instead of using a negative word like palāyana (‘escaping’ or ‘running away from’ reality), P T Narasimhachar (Pu Ti Na) uses the words bhavanimajjana (immersing the ugly materialistic world) and laghimakauśala (momentum to jump beyond the horizons). We are not aloof from reality but we drown the ugliness of the ephemeral world and transcend reality with that momentum.] Is it tough to write these stories? If not, is it easy? What are the strengths and limitations of the models for stories provided by this magazine? Further, what is the value of such stories? Many questions like these haunt intellectuals. Even if we keep aside the Chandamama, a lot of dedicated research on such topics is under way. Thus being the case, what additional reasons can I give? We shall see that in the next essay.

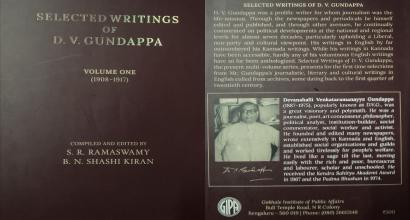

This is a translation of a Kannada essay by Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh titled ‘ಚಂದಮಾಮ’ದ ಚಕೋರ ನಾನು from his remarkable anthology Abhiruci.

Edited by Hari Ravikumar.