Typically if you ask a middle-aged person—or even someone in their thirties—who is a connoisseur and from a middle-class family, to describe a few sweet memories from his childhood, among the many things he would mention, without fail, you will hear the name of the periodical Chandamama, isn’t it? My tender and unforgettable sweet memories were formed by reading Chandamama. It is true that like me, billions of Indians have experienced joy from reading it. Personally speaking, Chandamama was among the cultural media that shaped my artistic taste. I find great joy even today when I read the issues of Chandamama – not in its modern avatar but the ones that were published in the decades before the seventies and eighties, particularly the ones from the fifties and sixties. Many of its old issues are safe in my collection, like treasures, and they are not available to anyone for borrowing. During lunch or dinner, breakfast or snacks, there is no greater pleasure than reading Chandamama. It is not only the abode of divine beings but also an entire world of learning and culture.

Chandamama was started sometime during 1947-48, soon after the country gained independence, thanks to the passion and courage of people like Nagi Reddi, Chakrapani, Kodavaganti Kutumba Rao, and others. The noted artist and illustrator M T V Acharya served the magazine for long; his illustrations for the Mahābhārata Citramālā and his role as the editor of the Kannada edition are unforgettable. I got the chance to read these old editions only in subsequent years. Chandamama, which was published in the highest number of Indian languages, and sold millions of copies, had no competitor. When Chandamama started a Sanskrit edition in the late eighties, it was truly an achievement in the fields of culture and media. Chandamama used innumerable stories from Indian culture for its existence and growth – Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, Pañcatantra, Kathāsaritasāgara, Purāṇas and others; this also includes the Jātaka tales and other stories in Pali (Magadhi), an offshoot of Sanskrit. The world discovered all these stories thanks to the Sanskrit literary tradition. By starting a Sanskrit edition, Chandamama partly repaid the debt that it owed to the tradition; this is praiseworthy indeed. Chandamama started in Telugu, soon followed by Kannada, and after that it spread to Tamil, Malayalam, Hindi, and English; it further expanded to Marathi, Odia, Sinhalese, Bengali, Gujarati, and so on. The discerning connoisseurs will remember the unique fragrance of its Telugu editions. It is for this reason that some people cynically blamed it as a scheme of a few Andhra people living in Madras; even so, Chandamama became to a large extent a pan-Indian magazine. To cut a long story short: if we keep aside the style of the illustrations, which are uniquely South Indian, we can say that a breathtaking and attractive world of beauty and values—pan-Indian in nature—were shared with children. But everyone, irrespective of children or adults, enjoyed it and continues to enjoy it even now. My present purpose is not to expand on the stories or achievements of that magazine. I am setting out to share the practical value that I have got and the saṃskāras that I have imbibed by reading Chandamama.

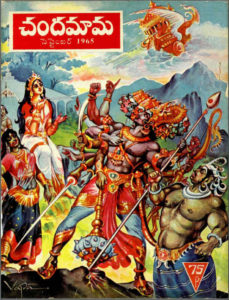

I was born and brought up in an ordinary middle-class family where I grew up listening to stories narrated by both my parents. From my father, I heard stories of the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata; from my mother, I heard stories of animals, birds, and fantastical beings – these filled me up. However, all of this combined was given to me by Chandamama. I learnt to read when I was five and by my sixth year, I had begun reading Chandamama. This was my mother’s gift. In the very first issue that I read, the story of the Mahābhārata had started in a serialized form. What is more memorable to me was the title page of that issue – it depicted the birth of Karṇa. By that time, around five years had passed since Vaddadi Papayya (‘VaPa’) had started sketching the title page of the Chandamama issues. (VaPa lived in an unknown village in Andhra and without any publicity toiled all by himself. Till the end, his life ran that way. His signature was an exclamation mark between two zeros. ‘In between the two zeros of birth and death, life is a mystery’ was his interpretation. This brings memories of a piece-verse from Kuvempu’s anthology ‘Mantrākṣate.’ Here, inside a zero, between two exclamation marks, there is a question mark that symbolizes life. If birth and death are faint and unknown facts then life itself is a question mark is Kuvempu’s opinion.) VaPa’s style, imagination, colouring, and brush-strokes are unique; indeed I am extremely fond of them. VaPa also used to illustrate with his quaint sketches yet another Telugu publication, Yuva, which was published by the same people who published Chandamama. His Rāgamālā paintings are extremely innovative and original. The paintings that M T V Acharya made for the main page of the Mahābhārata story were inspired by the Hellenic and Hellenistic styles—with geometric shapes—while the colouring and background followed the Bengali style; these were attractive in their own way. However VaPa’s imagination seems closer to the exaggerated and embellished style of Sanskrit poetry; they were extravagant and free-flowing. Greater restraint is seen in Acharya’s style, while in VaPa’s we see greater clarity. At any rate, Chandamama’s cover page would be supremely beautiful. (The back cover would also be attractive; they would correspond to the serials that contained Mowgli’s stories, Pañcatantra, India’s history, stories of national leaders, Buddha’s stories as well as the translations of the Greek epics Iliad and Odyssey as ‘Bhāvānusundarī’ and ‘Rūpadhārā’s Journey.’)

The pictures inside Chandamama would be as lovely and uncommon as the front page. The visual life-force of the magazine were Chitra (Raghavulu) and Shankar. Chitra’s work was inspired by the western style. When sketching people, Chitra emphasized things like a person’s behaviour, muscles and flesh, and the detailing; on the other hand, Shankar was clearly inspired by the Ajanta-Bengali style and gave more value to the contours of the figure and the gentleness of the form. Accordingly, if Chitra got a chance to draw the sketches for stories that were fantastical and rich in imagination, Shankar got opportunities to draw sketches for stories from our tradition, history, and the epics. The sketches of both were filled with expressions of feelings; they would be brimming with life and excelled in beauty. In both the varieties of serials, the sketches were for a long time, drawn with five colours. The pictures of the remaining stories would be printed in different shades of single colors - blue, orange, green, or violet. But in recent decades, although it is the fashion to print everything in multicolour, because the era of those great artists has come to an end, the beauty, attractiveness, feelings and emotional connection have all become dull. Even so, among those who came later, Jaya and Raji drew particularly well.

The contents of Chandamama have changed from time to time. When it was in its early days, Chandamama also included story-telling and poetry (especially the simple, metrical verses of Navagirinanda). There were a few standard features like Question and Answer, Chandamama Gossip, Strange mysteries from around the world, Indian history, and Leaders of the Indian freedom movement, but they never consumed more than four or five pages. Therefore, instructional and merely informative portions were extremely less. It is my belief that the uniqueness of Chandamama lies here. The present-day children’s magazines have as their central theme quiz-type information, thus crowding their pages with brutal reality and formal knowledge of subjects such as science; the joy of wonder and the beauty of imagination have altogether disappeared. With a view to touch upon this dimension of wonder and imagination, cartoons and comics have spawned entertainment that is divorced from reality and filled with pandemonium; they have entirely forgotten the values that are essential to and inseparable from ānanda (enjoyment). The only exception that I have found to this is India Book House’s Amar Chitra Katha. This topic deserves another dedicated article. It is a childhood magazine that I worship greatly. For the present let us look a little more into Chandamama’s elegance and beauty.

This is a translation of a Kannada essay by Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh titled ‘ಚಂದಾಮಾಮದ ಚೆಂಬೆಳಕಿನಲ್ಲಿ’ from his remarkable anthology Abhiruci. Edited by Hari Ravikumar.