This article is based on Ramaa Bharadvaj’s illustrative talk on June 18, 2017 at the workshop on Vyāsa, Vālmīki, Kālidāsa, and Guṇāḍhya at Chinmaya International Foundation, Veliyanad, Kerala.

It is presented in two parts for Prekshaa readers.

We, the performing and visual artists of India, have inherited our rich tradition of storytelling, from master raconteurs. Among these, Vyāsa, Vālmīki, and Kālidāsa stand out prominently for providing rich fodder for our imagination. While their works can be categorized as poetic literature, another noteworthy writer named Guṇāḍhya, and his Bṛhatkathā deserve an equally revered place in India’s literary gallery.

The Bṛhatkathā stories contained the wisdom of life narrated through characters ranging from gods and kings, to animals and birds, and is said to have influenced India’s beloved book of stories, the Pañcatantra. As a derivative of the Bṛhatkathā, Pañcatantra Fables too are an exceptional source of life’s profound wisdom, expressed in a most accessible style.

While those who intellectually engage with these stories may look for symbolic intentions and philosophical implications, it is the artist, that keeps the rasa of these stories alive. While reinterpreting them through theater, dance, or puppetry, the artist provides the heart to these works, thus freeing them from narrative fossilization.

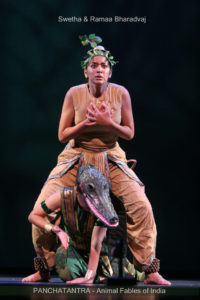

Through revisiting my dance-theater production “Pañcatantra-Animal Fables of India” (created when I lived in California USA), I share the conceptual and aesthetic processes that went into choreographically translating tradition for young audiences. I found that these stories, with their myriad emotional complexities of humor, pathos, jealousy, anger, wonder, and courage, lent themselves magnificently to be structured through the medium of dance, especially for a global audience.

Translating Tradition - An Immigrant Experience

The challenge for traditional arts practitioners in the diaspora setting is that our working arena is a non-native cultural environment where the arts, customs, and traditions, that have had a history of generational transmission as a Lived experience, are not practiced as a Lived-experience but as a Learned-experience. In such a habitat, the creative dexterity required of immigrant artists increases.

During my 31-year dance career in the US, my sharing of the cultural tradition was not about a habitual reproduction of inherited artistic-techniques, but about communicating my innate Indian-ness through the medium of Dance. I consider live theater to be a collaboration between the artist and the spectator and as such, I find statements such as “I dance for myself”, or “I dance for God, and God alone”, to exhibit a certain pomposity. In this regard, I recall Swami Tejomayananda’s reflection on the ‘Artist-Art-Rasika’ relationship:

An artist might say ‘I did it as a worship of God’ but if all the people who are sitting (in the auditorium) did not enjoy, then the offering is not complete. If we know that Paramatma alone is sitting here in the form of all these people and then perform, it is something special.

In this sense, having my work resonate with my viewers has always been important for me.

However, my desire to translate Pañcatantra stories through dance-theater was born not out of any craving for novelty, but out of necessity, when I encountered a genuine personal need for recreating my inherited artistic traditions.

Desire - The Mother of Invention

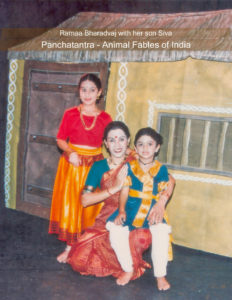

It was 1992, and my son Siva had just turned 3. Being a dancer, I decided that he would go where not many 3-year old Indian boys have gone before, and do what not many 3-year old Indian boys have done before. He would go to Indian classical dance performances and sit through the whole thing! But my son had other plans. While I sat in the auditorium, he ran around in the lobby, with other 3-year olds, chased by their respective dads.

This amusing scenario raised three pivotal questions in my mind:

- Are we diaspora artists being true cultural representatives, or have we settled into an artistic comfort zone (or creative apathy)?

2. Do we strive to rediscover our rich traditions, or are we merely using our traditional arts as a cultural pillow for us migrated adults to snuggle into, for curing our own homesickness?

3. Are not our ABCD children (American Born Confused Desis), as they are unfortunately called, our first real transnational audience? Can we brag about being cultural ambassadors of our tradition in a foreign land, when we cannot even seem to draw our own children in?

At that time, I used to read him bedtime stories from the Pañcatantra fables, and the dancer in me would jump, leap and make faces. Siva was riveted to my “Presentation”. It was then that I decided I would animate these fables on stage for him, and for other young children who were running around in theater lobbies.

It took two years of research and preparation – my husband and I took a second mortgage on our home in the US to fund the project - and Pañcatantra was brought to the stage in 1994.

About Pañcatantra Fables

Believed to have been compiled 2500 years ago, Pañcatantra is a nīti-śāstra - a science dealing with the conduct of life. It presupposes that one has considered and rejected the possibility of living as a saint. It attempts to answer the question of how to gain the utmost gratification from life in a worldly existence, not in a frivolous manner, but through dharma-based principles. Dharma is not to be understood as an explicit ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. It refers to the innate nature of a thing/person. For example, it is the dharma of fire to burn, of a bird to fly, of a warrior to fight, and so on. In the tapestry of life, every creature has its dharma and Pañcatantra fables explained the enjoyment of life on this basis.

The stories were told by Viṣṇuśarma, a Brahmin scholar, who was ordered to educate the three lazy princes of Mahilārūpya. Viṣṇuśarma taught them the art of statecraft, along with lessons in philosophy, psychology, astronomy, human relations etc, all in the form of 86 clever and witty animal fables. The verses spoken by the animal characters were quoted from sacred writings. Arthur W. Ryder, who wrote a comprehensive English translation, compares this use of verses to that of having an English beast fable in which all the animals "justify their actions by quotations from the Bible or from Shakespeare".

Viṣṇuśarma divided his fables into pañca (five) tantra (treatises). These were:

Mitrabhedam – Breach in friendship

Mitraprāptikam – Gaining friendship

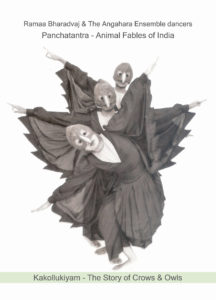

Kākolūkīyam – Story of owls and crows

Labhapraṇāśam – Loss of what is gained

Aparīkṣita-kārakam – Results of unexamined (rash) acts

Within six months, he turned the princes into experts in the complexities of political ethics.

Some historians even say that in 600 to 700 BCE, Pañcatantra tales traveled to Babylon and Greece through traders who narrated them as nighttime entertainment in trading colonies, and thus they became the forerunners of the famed Aesop's Fables.

Adapting the Fables

During my research for this production, some questions arose in my mind.

1. Why did Viṣṇuśarma select animals to be the voice for this intellectual subject? I realized that animal characters have the power to touch a delicate part of the human psyche in a way that human characters cannot. Whether it was Viṣṇuśarma who created the Pañcatantra animals, Walt Disney who created Mickey Mouse, or the creators of Sesame Street’s Big Bird and Kermit the Frog, they were all aware of this fact. (A real-life example of the impact of animal characters is found in the animated film ‘Babe’, about a baby pig. When it was released, the sale of pork dropped dramatically in the US.)

2. Did the author see the similarity between the state of equilibrium needed for the human mind for surmounting the challenges of life and the equilibrium maintained by Nature? After all, Nature does possess a great capacity for regeneration, and for survival, which is what Pañcatantra is all about.

3. Could a reinterpretation of the Sanskrit words in the original work redefine the message of the Pañcatantra to deliver a commentary on environmental ordeals?

I found, that through a contemporary interpretation, I could embrace Pañcatantra’s allegorical structure for raising philosophic questions about human perception of “Nature” and global ecology in today’s world. Thus, if Viṣṇuśarma’s Pañcatantra talked to the sons of king Amaraśakti who were to inherit the kingdom of Mahilārūpya, my Pañcatantra would speak to the sons and daughters of the modern world who will inherit the kingdom of Earth.

In conceiving the storyteller’s dialogues, I drew inspiration from the speeches of Native American leaders, writings of American Naturalists such as Henry David Thoreau, philosophers from around the world, and from our own Ṛg Veda.

For example, although the first chapter of Mitrabheda is literally interpreted as “Breach in Friendship”, I was inspired by a deeper philosophical implication found in the Ṛg Veda, where Mitra is described as a heavenly Being, who lays down the Ṛta Dharma, a law which dictates the peaceful co-existence of all life forms. Straying from this dharma causes a tear in the tapestry and creates a breach (bheda) in the cosmic and ethical laws of Mitra. When this interpretation of the word mitrabheda unveiled for me, the story of the lion, the bull and the jackal became more than just about a rift in the friendship between two creatures. It carried symbolic connotations about personal, communal, and global miseries that result when harmony and balance are fractured.

I found each of the five Tantras to lend itself aptly to provide environmental thoughts and adaptation, and I braided these together by scripting a conversational narration between a mother and her young children as seen in the video sample below. This biographical intent became truly meaningful, when my son Siva, who had turned 5 by then, not only agreed to act on stage but also recorded his dialogues in his own voice. This thrilled me, for, after all, he was the artistic muse who unlocked the gate for this journey.

Whereas weaving the connective story for the five Tantras flowed as if guided by some higher supervision, bringing it on to the stage entertainingly, and without losing the classical eloquence, presented challenges from multiple angles. In Part-2 of my essay, I share how I navigated the choreographic landscape.