The Vagaries of Comforts and Discomforts

Why are there difficulties, troubles, sorrows, and atrocities on earth? Nobody desires for these. Everyone wants to be comfortable and happy. Merely by aspiring to be free of troubles doesn’t lead to such a state; just because one wants to be happy, it is not easy to attain. Some have only happiness in their lives while some others have only difficulties.

Let’s assume that the two—joy and sorrow—exist in different proportions in each person’s life. Why should they be in different proportions? Why can’t we have an influence in varying their proportions? The difficulties that some people encounter are solved completely. In the case of others, it is solved partially. In the case of some others, they have to succumb to the problem. How to solve the problem or to come out of the difficulty? Is it by using the intellect? Some people are not smart; some people have brilliant minds. Why is it so? Even when the intellect is strong, sometimes it becomes blurred and gets cheated. Even the most brilliant minds get caught with difficulties and suffer. If one is sagacious, the impact of the problem is lesser; it’s like the cream forming over boiling milk. At times it feels like cheating oneself.

In medicine, there is an antidote for a disease; is there similarly a remedy for difficulties? It appears that there is some remedy – just like hunger and thirst are quenched by food and water. There are many diseases that remain unaffected by medical interventions and do not have a cure as yet. Likewise, several problems in the world have no ready-made solution; they seem to come of their own accord and then disappear on their own. It doesn’t seem to adhere to the laws of time. Day follows night – such is the law of time. The blossoming of a jasmine flower or the ripening of a mango fruit are governed by the law of time. Are difficulties similarly time-bound? This difficulty has been succinctly captured in the Kannada proverb “ಅಂತೂ ಇಂತೂ ಕುಂತಿಯ ಮಕ್ಕಳಿಗೆ ರಾಜ್ಯವಿಲ್ಲ” loosely translated as ‘One way or another, the children of Kunti are deprived of the kingdom.’ In essence, the saying seems to point out to the fact that irrespective of however much they adhered to the path of dharma, they did not reap the benefits of royal comforts. They did not get it at first, indeed; they did acquire it later. But they were dejected by it perhaps; the thought of the kingdom was not a mouth-watering proposition to them. Let alone her children, what is the kind of happiness Kunti enjoyed? As a child, she grew up under another’s care [Though the daughter of King Śūrasena, she grew up as the foster child of King Kuntibhoja]. Later on, although she had a husband, she could not enjoy conjugal life; she lived on roots and fruits in the forest, with her body getting emaciated; she roamed around draping herself in the hide of an animal or the bark of a tree; she begot children from different deities; she became widowed; tagging along her children and her co-wife’s children, she had to tap the door of her [unwelcoming] brother-in-law; she had to live on the morsels thrown in her direction; and even while putting up with evil machinations, she had to raise her children. Being a silent witness to the many daily perils that her children faced, she was always unsure about the next moment and lived like one who would die at any moment.

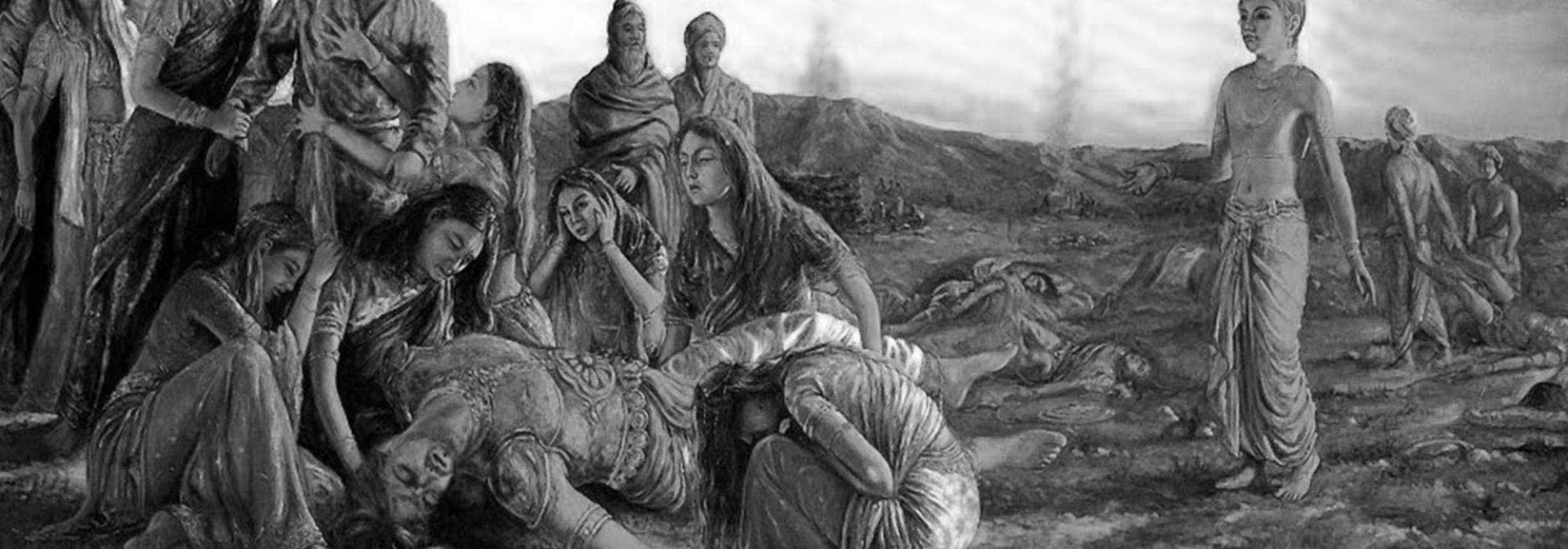

Thanks to good fortune, she and her children survived a ghastly unceremonious death in the fire that burned the house of wax; and ironically, that is how her life ended finally [in a forest fire.] Perhaps, the reason for such an end was the companionship of Dhṛtarāṣṭra and Gāndharī; it such a lowly death for them! Kunti’s situation was so much better; Gāndharī’s was one fraught with injustice. What evil deed had she committed to marry a man blind in both eyes? Were there no other eligible princes? She did not complain and did not behave rashly like Ambā did. While her husband’s blindness was a divine provision, she blinded herself with her own hands, thus doubly marrying blindness. She never expected more happiness than her husband; she never pained him; and she was hailed as a pativratā (chaste wife). What was the use of people praising her as a chaste wife – did it result in any gain? Her husband was blind; her children, on the other hand, were warriors who lacked wisdom; not one child, but a hundred; having tread the wrong path, all of them died in the battle right before of her eyes, with none remaining even to continue the lineage. The only daughter she had was widowed. Having experienced all this, she was burned from within and succumbed to the forest fire. Was this the reward for her being a chaste wife and a tapasvi?

In a sense, Dhṛtarāṣṭra was a more fortunate one; though born blind, he got married to a woman of good character. Although he was not suited to rule the kingdom, he was respected even more than the king and was regarded highly as an elder in his lifetime. He must have got a great deal of peace, happiness and solace from Gāndharī. One can put up with anything in life, but not the protest of ‘My way is mine, your way is yours!’ that arises as a result of foolishness, stupidity, and cantankerousness; while the Mahābhārata war was fought for a mere eighteen days, this is a daily battle. This leads to constant trouble. Dhṛtarāṣṭra did not have to suffer this kind of an ordeal. There have been instances where Kunti opposed her husband and spoke against him, displaying her tendency to erupt in anger. At times, she even bossed over her co-wife Mādrī and spoke harsh words to her. Expressing her disappointment towards her children, there are instances where she complained about her dissatisfaction about the situation. But we do not find any instance where Gāndharī and Mādrī behave in such a manner.

When compared to Kunti, Mādrī was far more beautiful, noble, and tender; leaving her divinely beautiful twins with her co-wife, Mādrī joined her husband on her last journey. Whether she got reunited with her husband in the other world or not, whether she lived happily with her husband in her afterlife or not, what was the joy she got while alive? It is been said in the epic that Bhīṣma, upon looking at her incomparable beauty, paid a lot of money in order to purchase her for Pāṇḍu. Being born as such a beautiful princess, she had to fall prey to the game of money, marry a diseased man, put up with the tantrums of the co-wife, finally succumbing in the jungle – what sin did she commit to deserve all this?

It is said in the epic that Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s mother was the cause for him being born blind in both eyes. Ambikā was the daughter of a king, beautiful and youthful; she got married to a king and led a family life with him, but was widowed without having any children through him. Upon her mother-in-law’s coercion, she agreed to undergo niyoga. While she expected that Bhīṣma or some other good-looking son of a great king would be brought for this purpose, Vyāsa came there, dampening her spirits. Looking at this old and ugly sage with red eyes, red coloured matted locks, and terrible body odour, either out of shock or out of fear, she closed her eyes; but was this her mistake? Ambālikā got scared looking at him; was that her mistake? As for Ambikā and Ambālikā, they at least spent a few days in the company of their husband and they also begot children (from Vyāsa). Ambā did not get even this. Though a beautiful princess, she was not wanted by anyone; she did not get married and out of sheer despair, ended her life by jumping into the fire; such was her fate. In her following life, she might indeed have taken birth as Śikhaṇḍi and been responsible for the death of Bhīṣma, but what was the happiness she acquired from that? What kind of sorrows did she rid herself of? If as Śikhaṇḍi, she was aware of her previous birth, she could have attained the vengeful satisfaction of having shown the same cruelty to Bhīṣma as he did to her. But the epic doesn’t tell us if Śikhaṇḍi had such knowledge of her previous birth.

Note: It is said that Śiva had given a boon to Ambā that included the memory of the previous birth:

स्मरिष्यसि च तत्सर्वं

देहमन्यं गता सति।

वधिष्यसि रणे भीष्मं

पुरुषत्वञ्च लपस्यसे॥

(Udyoga-parva 188.12)

“You will remember everything even when you have taken on a new body. You will kill Bhīṣma on the battlefield by taking on a masculine form.”

To be continued.

Thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for his astute feedback.