Let us look at Yakshagana and its allied art-forms from the point of view of angikaabhinaya (communication through the body and gesture language). Kuchupudi and Bhagavatamela are rich in angikaabhinaya. However, in recent times, Kuchupudi has been relinquishing its theatrical format, i.e., the format of Yakshagana and Kalaapa, and is heading towards becoming a dance (nrtya) format. Although, this is a positive development in one sense, for it means we will have gained a beautiful dance (nrtya) form, it is also sad that the complete theatrical performance (naatya) of Kuchupudi is moving towards extinction. It is also sad to note that Melattur Bhagavatamela has given up its traditional angikaabhinaya, which was both beautiful and aesthetically appealing, and has taken to a mere imitation of Tamil Nadu’s Sadir-Dasiyaattam (popularly known today as Bharatanatyam). Of late, however, it is commendable that a few artists of Melattur Bhagavatamela, inspired by Dr. Padma Subrahmanyam, are putting efforts to improve their anga-shuddhi (neatness and discipline in training the body).

[contextly_sidebar id="1f6kqXbrGsTZ0muXHM2D9iD3GwR9xRHO"]

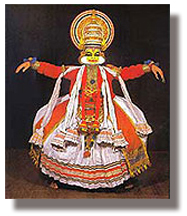

The performing arts of Kerala such as Koodiyattam, Krishnanaatyam and Kathakali have limited their angikaabhinaya by relying on works like Hastalakshana-Dipika, which is only a manual of hand gestures. These forms only employ hand gestures and exaggerated movements of the eye-brows, lips and cheeks, i.e., mukhajaabhinaya. It is quite unfortunate that these forms do not use chaaris, nrtta-hastas and several other beautiful movements and also those that can bolster Loka-dharmi. It is all the more regrettable that the basic sthaanaka (posture) of these forms from Kerala are parshni-paada and vaishaakasthaana, which limit free movement of the body. Having said this, the perfection they have attained in expression through face and body as a result of intense and disciplined practice is laudable and worth of emulation.

Performing arts such as Doddaata, Mudalapaaya, Kelike, Ghattadakore, Terukkutu, Chindu, Maala lack variety in their angikaabhinaya and lack a systematic grammar. Even so, the only saving grace is that the movements follow certain rhythmic patterns. Among these, Chindu-Yakshagaana has retained lively aangikaabhinaya. The southern variety of Yakshagana, i.e., the Tenkutittu lacks aesthetic footwork thanks to its affinity for odd rhythmic patterns. This has also resulted in poor hand and body movements in Tenkutittu. Of late, artists seem to think that just high-speed swirling and making somersault-like movements constitute nrtta. However, thankfully, Tenkutittu uses hastaabhinaya (hand gestures) well and incorporates Loka-dharmi too, unlike the art forms of Kerala. Moreover, it is embellished to a certain extent by different sthaanakas (stances) and rechakas (subtle movements of hip and neck).

The Badagatittu Yakshagaana, though it does not command superlatives, has more laalitya (gentleness), ojas (energy) and freedom for movement, as it uses rhythmic patterns which are even. The style practiced in the Kundapura region of Karnataka, in particular, has beautiful sthaanakas and footwork, which gives it a certain majesty. It even has a few chaaris, nrtta-hastas and karanas, which are the fundamental components giving it a unique style of nrtta. Nevertheless, it is pitiable that many artists are under the illusion that non-aesthetic footwork and movements of knees constitutes good aangikaabhinaya. The usage of abhinaya-hastas (hand gestures) of the Badagatittu variety of Uttara-Kannada region of Karnataka is quite elaborate and apt too. The sthaankas, rechakas and parikrama (circular movement) of the rest of Badagatittu Yakshagana are pleasant to watch. In summary, even in angikaabhinaya, Paduvalapaaya Yakshagaana hangs in limbo between up-gradation and degradation.

We need not heave a sigh of relief just because all these traditional performing arts have retained their grandeur in angikaabhinaya and that they have not resorted to cheap Loka-dharmi techniques. This is because, in Yakshagana, once the singing and dancing are over and the actors start conversing on the stage (vaachikaabhinaya), they tend to forget the roles they have put on and start speaking in a colloquial manner, with worldly expressions. This has often disappointed the audience. This degeneration is all the more prominent in Terukkuttu, Chindu, Maala, Torpu-Yakshagana, Doddaata, Mudalapaaya, etc. The advantage in these forms compared to the Paduvalapaaya Yakshagana is that, the dialogues are scripted and memorized by the actors. This allows them to use angika (body language), even while speaking. However, the dialogs in Paduvalapaaya Yakshagana are extempore and come from spontaneous inspiration of the artists. This is laudable, but at the same time detracts the focus of the artists away from angika. At times, the angika of the artists who get carried away with extempore-dialogue-delivery, tends to slacken, harming the propriety (auchitya) in the presentation of the character.

Adapted by Arjun Bharadwaj from the original Kannada