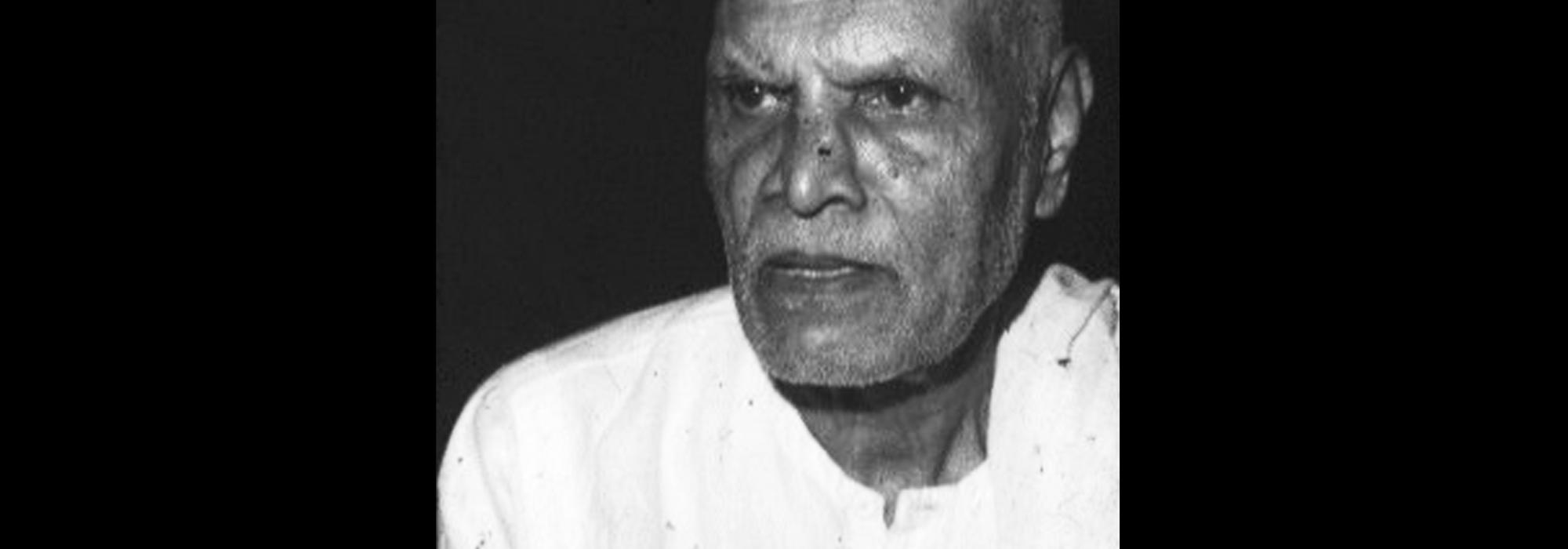

Gorur Ramaswamy Iyengar attained fame in Kannada literature by his creative nonfiction writings and hundreds of stories that have humour as their mainstay. Among those writers whom the readers specifically identified as humorists, Gorur Ramaswamy Iyengar and Na. Kasturi were the foremost. The characters that Gorur created several decades ago have remained enshrined in the hearts of readers even today; this bears testimony to the emotional richness in his writing. People who wish to become acquainted with the eccentricities and diversity of village life fifty years earlier [i.e. the 1930s] must read Gorur’s writings such as Garuḍagaṃbada Dāsayya, Namma Ūrina Rasikaru, Haḷḷiya Citragaḷu, and Bailahaḷḷi Sarvè. Just as V K Gokak said somewhere, Gorur’s writings are the Mahābhāratas of the villages, they are a universal and aesthetically-rich view into village life.[1]

Writings Rich in Emotion and Essence

If one deems Gorur merely as a humorist, it would do him injustice. In his works, we find several instances of writings that are profound and abundant in values and goodness. When we read his lofty biographical sketches such as Bhārata Bhāgya Vidhāta (about Gandhiji), Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Satī Kastūrba, Jagattina Mahadvyaktigaḷu (‘Great Personalities of the World’), and so on, the ‘humorist’ Gorur doesn’t come to mind. Another specialty is that Gorur has devotedly toiled, just as for his independent creative writings, in translating influential works from other languages into Kannada. The tens of translations that he undertook are the fruition of his personal desire that the Kannada language and literature as well as the lives of the Kannada people should qualitatively improve. Gorur has performed a great service by translating into Kannada numerous works such as: the treatises and writings of people such as M K Gandhi and Mahadev Desai, V C Khandekar’s novel Krauñca-vadha, Narayan Agarwal’s Mother Tongue Medium at Work, K M Munshi’s Bhagavan Kautilya, the literary essays of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhaur, and so on. In the realm of spiritual writings, as early as forty years ago [c. 1921] Gorur translated Swami Vivekananda’s Bhakti Yoga into Kannada. Gorur translated into Kannada Kāñci Kāmakoṭi Pīṭham’s Śrī Candraśekharendra Sarasvati’s lectures on the Vedānta with the title Jagadgurugaḷa Divyabodhè and himself published the work. Being a well-rooted and noble Śrīvaiṣṇava [and hence brought up in an atmosphere of viśiṣṭādvaita], the fact that he toiled so enthusiastically to spread the message of an ācārya of advaita is an indication of the magnanimity of Gorur’s mind.

Nobody can claim that Gorur was merely a focussed and diligent writer when they learn about the following – he worked silently sans fanfare in areas like prohibition of alcohol, propagation of khādi, development of villages, adult literacy and education, etc. and sincerely strove for the welfare of people as a Member of the Legislative Council (MLC) and as a University Senate Member.

When we consider the personal life of Gorur, our palms come together in salutation. Although he has attained special fame in the realm of literature, he continues to be enthusiastic in the political arena as well as various facets of the social sector. He was a person who had actively participated in the Freedom Movement and faced several hardships; he also went to jail during that period.

A Devoted Follower of Gandhi

The truth is that Gorur was, at a fundamental level, a devoted follower of Gandhi. A significant portion of his writings arose to complement those ideals. He came under the influence of Gandhi at the tender age of sixteen. From then until the present time, Gorur has shaped his life by treading the path lit by Gandhi’s ideals. In 1920, when Gorur was a high-school student in Hassan, Lokamanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak breathed his last. The atmosphere of devotion to the motherland engulfed the entire nation and Gorur too was drawn to it. As he himself has said, “I was overcome by an obsession, a madness for freedom and swarajya. At all times, my mind was filled with that thought. I dreamt the same in my sleep too… whenever I read in the newspapers that thousands and thousands of common citizens went to prison for sparking revolution in various parts of India, I would think: ‘Why am I sitting here, mindlessly traversing English, Algebra, and Science?’ I felt that it was superior to face a bullet and die rather than live as a slave…”

In Dharwad, under the Presidency of the Late Hukkerikar, Gorur gave a speech criticizing the British government and subsequently, slipping from the hands of the police, he went to Bombay and from there reached Ahmedabad to become a volunteer for the Congress party. (For some time, he also worked as a compositor for the journals Navjivan and Young India.) Being in the presence of Gandhiji for a long time as well as the association with Kakasaheb Kalelkar and Acharya Kripalani made Gorur’s personality noble and magnanimous. “Gandhiji was a light who resided in my heart. Before every single activity that I undertook, I would ask, ‘What would Gandhiji say to this?’ and then proceed…”

During Gandhiji’s visit to the Southern country and his tour of Karnataka, Gorur sought his permission and joined his team of volunteers. Gorur has recorded the details of that journey in his treatise Gāndhijiyavara Dakṣiṇayātrè (‘Gandhiji’s Journey to the South.’) During his later years, he joined the Bangalore-Kengeri Gurukula and lived a spartan life. In those days, Gorur wrote a number of essays and books that nourished devotion to the motherland and made it popular. With the intention of turning people’s attention to the lifestyle of the villages of India, Gorur wrote Haḷḷiya Citragaḷu (‘Village Portraits,’) Namma Ūrina Rasikaru (‘The Connoisseurs of our Town,’) and other works, which incidentally turned out to be great works of literature.

Profusion of Humour

Gorur’s writings are filled with dainty humour. However, it is not bereft of reason and good sense. Through comedy enkindled by unique situations, lofty ideals and noble human values shine in his writings – for those who can perceive it intricately. Those who read his writings merely for its humour will find it, needless to say, readily accessible and in copious quantity. D R Bendre’s words of praise run thus: “In Gorur’s writings, there is story; creation of characters; there is laughter and there is pain; there are descriptions; hypocrisy, ridicule, satire, intrigue; if you need it, there’s philosophy and if you don’t, there’s light-hearted banter. The white sheet of humour is spread out on the shrubs [of events] and underneath it, the sorts of creatures that thrive! Be it kings, barbers, brāhmaṇas, Muslims, dāsayyas[2], [yakṣagāna artistes] who perform bayalāṭa (outdoor drama), subedars, or members of the hòlèya community – when all these people have been strung together like a garland with humorous poesy, who wouldn’t deem it to be praiseworthy? ...a brilliance of language that is able to recognize and describe the humorous river that is latent but flows in the life of the common folk.”

The purchase of a garuḍagamba from a sādhu—although they had absolutely no need for it—simply because it was dead cheap at ten annas, and the travails of trying to dispose it; the courage of the group of brāhmaṇas—who were unable to face five Muslims although they were several in number—that made them say, “They’re running off with just a cartload of tiles, aren’t they? If it goes, let it go. It’s pointless fighting over such trifles;” the bayalāṭa that was debauched due to the partaking of ‘Rāma-rasa’[3] – having encountered tens of such episodes in Gorur’s stories, rare is the man one who hasn’t been moved by them. Having been born in a brāhmaṇa family, Gorur observed and wrote extensively about the idiosyncrasies and rough edges of the community. Keśavācārya—a latter-day avatāra of Mahāviṣṇu—and other vaidikas enjoy a papaya fruit, step outside to wash their hands; there is no water and yet they make some noises with their copper pot before returning [to indicate to the world that they have indeed washed their hands, a norm that was prescribed]. But the selfsame brāhmaṇas take exception to Nani, who steps out with nothing in his hand. Nani tells them, “I had a few three-paisa coins in my pocket and I made a noise with that. After all, the pot that you took with you was also made of copper [just like my coins].” The response given by Keśavācārya to that was, “Although the ritual is destroyed, the form must not be desecrated, dear fellow!”[4]

This is the first part of a two-part essay that has been translated from an article published in the February 1981 issue of ಉತ್ಥಾನ (Utthāna). It was written when Gorur Ramaswamy Iyengar (1904–91) was still alive. Heartfelt thanks to the author Dr. S R Ramaswamy for reviewing the translation. Thanks also to Arjun Bharadwaj and Raghavendra G S for their review.

Footnotes

[1] The original goes: ಗೊರೂರರ ಕೃತಿಗಳು ಹಳ್ಳಿಗಳ ಮಹಾಭಾರತಗಳು; ಗ್ರಾಮಜೀವನದ ವಿಶ್ವರೂಪ ರಸ ನೋಟ.

[2] Wandering mendicant-minstrels.

[3] Euphemism for an intoxicating drink.

[4] The original has: “ಆಚಾರ ಕೆಟ್ಟರೂ ಆಕಾರ ಕೆಡಬಾರದಯ್ಯ!”