Helplessness of the Government

I have mentioned earlier a statement that M N Krishna Rao used to repeat quite often: “When observed from one standpoint, the government is the most omnipotent body in a country. There is no other entity as strong or as independent as that. When seen from another angle, there seems to be no other entity as weak or as parasitic as the government. The government can rule only if people support it.”

During Mirza Ismail’s tenure, the citizens themselves had begun slackening the government’s regulations. The śāstras may declare ‘Dharmo rakṣati rakṣataḥ.’ Dharma can protect us only if we protect Dharma. How can dharma retain its capacity to protect us if it is crippled? Only if the people protect the decorum of the government will the government be able to protect the interests of the people. What if the people themselves turn against the government? What can any government do?

This is why the State could not wholesomely benefit from Madhava Rau’s honesty or competence.

During the tenure of Sir Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar, this discord intensified further.

As for the events that took place afterwards, I do not wish to critique them here.

Rise of the Democratic Era

We can consider the year 1947 as a line of partition in our country’s history. That year was a mountain range that stood tall between independent and dependent India. In this manner, it did not merely bifurcate the political scene in our history but also from the point of view of society, the period before 1947 was vastly different from the one thereafter. Even the structure of the government before 1947 was different from the structure of the government now. Similarly, the fundamental objectives of the State used to be something then and are something else now. Even the system of measurement was different. The earlier era was that of annas (āṇè) and pies (called dammaḍi or kāsu); now it is of Paise.* There is neither anna nor pie today. Earlier, inches and feet were in use; now it is kilometres. The days of seers (seru) and maunds (maṇa, equal to forty seers) have passed; today it is measured in kilograms and quintals.** Previously, it was a period of kings whereas now it is the era of ministers and touts. In this way, the external lives of the citizens from all aspects have become stranger than before.

Had these transitions occurred as a result of people’s willingness and efforts, nobody would have said anything about it. In the history of our society, changes have occurred often. Things have changed several times. A number of massive changes have also occurred; they have taken place right since the era of the Manusmṛti. But never had anyone ever sensed a feeling of revolution in the State when such changes took places. The changes during the past had come into effect in tandem with the situations of the State around that period.

Change is something that only happens naturally. It is like our bodily transformation. It keeps happening second after second. A child’s physical body would have changed in many ways by the same day a year later. A mouth without teeth would have developed teeth. In another few years, the teeth that had grown will have fallen. It is similar on a plant’s body as well. The changes in the society are no different. They need to happen without any noise or commotion, without attracting the attention of others. There should be no external constraints. The sattva, or inner essence, of the human body quite spontaneously adapts to an external situation. This sort of a change is neither dangerous nor troublesome. In our society, the transformations that occur in the lives of the citizens should be such. In other words, the sattva of the people should blossom.

What I would like to mention here is the fact that the changes that occurred in the last twenty to twenty-five years have come into effect through artificial constraints rather than in a manner that would aid the people’s sattva to blossom. The more artificial a change is, the more difficult it will be, and that much more unstable.

‘Svarājya’

It is true that the leaders of our country requested for ‘Svarājya.’ It is also a fact that everyone in the country was involved in seeking it. In that idea of svarājya, however, the most prominent intent was ‘the expulsion of foreigners.’ What sort of people should replace the foreigners was a thought that was never clear in people’s mind. Let the outsiders leave, let us rule our country by ourselves! This was the only objective that was definite. Now, let us assume that the slogan “Let us rule our country by ourselves” had the undercurrent of the idea of democracy. In such a case, how should the structure of the democracy be, how should its organs function, how should the relationship amongst those organs be, these details weren’t resolved as yet. Let us now look at an example.

In the year 1917, the leaders of our country thought of sending a delegation to England to impress upon the British gentlemen India’s fervour to claim svarājya. Bal Gangadhar Tilak was heading the meeting concerning the same. It was around the time when the venerable Annie Besant was running an organization called the Home Rule League; it was the time when the fundamental objective of Home Rule had been endorsed by Tilak.

That delegation had come to Madras on the way. Tilak’s committee was welcomed in Madras by Annie Besant, Sir S Subramania Iyer, and many other leaders; they organized a public lecture. I had been to Madras to attend that event. A massive crowd had gathered. Tilak and a few others delivered discourses. Just a few days prior to the event (in August 1917), the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu had made a declaration in favour of the British in their parliamentary session. That declaration was one of the most prominent phases in our country’s recent political history. During the course of that, the term ‘Responsible Government’ appears. While giving his speech that day, Tilak brought up this phrase and said, “What is this ‘Responsible Government’? What we demanded is Swarajya – Self Government. The British are offering to give us something called ‘Responsible Government.’ Is what they offer the same as what we seek, or are they different from each other?” Presenting his arguments thus, Tilak sparked both laughter and doubt among the audience.

It was only after several days that people realized that ‘Responsible Government’ was one of the many forms of a democratic system.

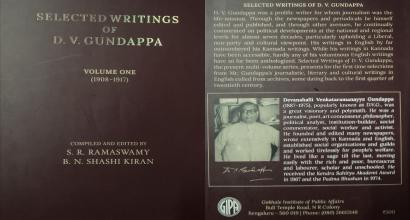

This is the second part of an English translation of the thirteenth chapter of D V Gundappa’s Jnapakachitrashaale – Vol. 4 – Mysurina Diwanaru. Edited by Hari Ravikumar.

* Twelve pies made an anna and sixteen annas made a rupee.

** Based on the region, the measurement of the seer varied but officially it was defined as equal to 1.25 kg.