Daśaratha, having ordered the anointing of Rāma, entered his home to convey the happy news to his queen. To his utter dismay, he saw Kaikeyī, dearer to him than his own life, lying on the bare floor. Just like a tusker fondling his female who has been struck down by an arrow in the forest, the old man caressed her with his hands. The lovelorn king said, “I do not understand why you are angry with me – has anyone displeased you? Don’t weep, my dear! Would you like someone to be punished, although he is not guilty of crime? Do you wish to let a criminal free? Do you want me to make a rich man poor or a poor man rich? Everything that is mine and my own self are under your control. I swear to live by your wish!”

Kaikeyī said, “You had promised me two boons in the past. I seek them right away. First, my son Bharata should be anointed as the crown-prince using the preparations you have made for Rāma’s coronation. Now, for the second boon, Rāma shall go to the Daṇḍakāraṇya for fourteen years and live there like a tāpasa donning matted locks, clad in barks of trees and deer skin. Bharata shall become the crown-prince this very day, unimpeded by obstacles. Rāma should also leave for the forest today.”

On hearing Kaikeyī’s vicious words, the great King was shocked and deeply pained, just as a deer gets mortally scared looking at a tigress. Daśaratha exclaimed, “Fie upon you!” and fainted, his mind submerged in tides of grief. Gaining his consciousness, he screamed at Kaikeyī. “Characterless woman! You are going to destroy our family! What harm has Rāma done unto you? He has always seen you like his own mother. It appears that I brought a venomous serpent to my house! The whole world sings Rāma’s glory. For what fault of his should I punish him so? I might give up Kausalyā or Sumitrā, my kingdom or my own life, but definitely not Rāma! The world may survive without the Sun, the plants without water, but I cannot live without Rāma! I will fall at your feet—please give up your evil resolve, O sinful one!” Daśaratha fell at her feet and was writhing on the ground but Kaikeyī would not give up her stance. She said, “You cannot call yourself dhārmic if you go back on your words!” Daśaratha lamented – “With the best of the humans, Rāma, gone to the forest and me dead, you may rule the kingdom as you wish, you ignoble woman!”

The king, in his grief, did not notice that the Sun had set. He begged the Nidrā Devī, “O star-bejewelled night! I pray with my hands folded – please don’t give way to dawn. Show me some sympathy! If you wish to go, go right away! I can’t look at Kaikeyī, the pitiless one!” He implored Kaikeyī to change her mind again and again, to no avail. He collapsed on the ground once again in a swoon.

Kaikeyī taunted him. “Having once given you word, why are you fallen on the ground? Truth is the highest dharma. Having given his word to the hawk, King Śaibya sacrificed his own body and Alarka gave away his eyes to a brāhmaṇa. The ocean too does not transgress his shore! If you do not honour my words, I shall end my life before your very eyes.”

Daśaratha who was thus verbally abused by Kaikeyī, like a thoroughbred horse mercilessly whipped, said, “I am fettered by dharma. I wish to see my darling, the dhārmic Rāma!” Listening to the king’s words, Kaikeyī commanded the sūta Sumantra to fetch Rāma. Thinking that Rāma was being summoned for his coronation, Sumantra’s heart flooded with joy. He sped to Rāma’s residence. It was almost daybreak.

Brāhmaṇas, ministers, the royal purohitas, and others had made all arrangements for the anointment of Rāma. Golden water-pots, the throne, a chariot covered with its seat covered with tiger’s skin – were all ready. Water had been brought from the saṅgama of Gaṅgā and Yamunā. Majestic elephants, women, musicians, bards, and many others who had gathered for the auspicious ceremony, could not spot the king. Sumantra asked them to wait a while, entered the magnificent mansion of Rāma, and conveyed the king’s message to him. As Rāma headed out with Sumantra in his chariot, a delightful din was heard from the crowd that was waiting to see him.

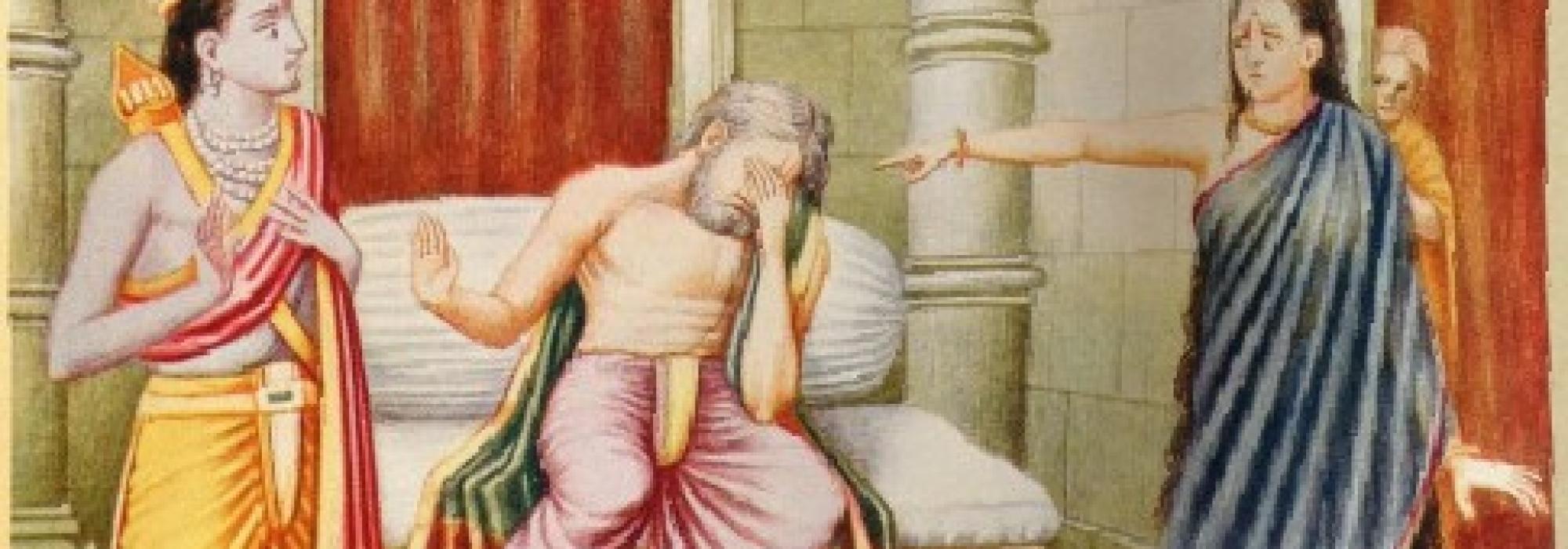

Rāma entered Daśaratha’s palace and saw his father, looking miserable, seated on a couch with Kaikeyī. Rāma reverentially touched the feet of his father and then his mother Kaikeyī’s. Daśaratha, his eyes filled with tears, merely uttered ‘Rāma!’ and was not able to see or speak any further. Rāma was frightened to see his father in this state, just as one who has stepped unaware on a poisonous snake. He wondered, Why does my father not welcome me gladly today? He used to regain good humour as soon as he saw me, even if he was angry. He asked Kaikeyī, “Have I unwittingly offended my father? He looks pale and does not talk to me. Is he suffering from a mental or physical pain? Has he heard anything improper in the conduct of Bharata or Śatrughna? If the king is angry with me, I would not wish to live for even a moment. Or, have you spoken harshly to him, either out of love or anger? Please tell me, O devi, what the king wants of me. I would jump into the fire or swallow deadly poison, if my father commanded me to do so. I will execute the king’s wish, I promise. Rāma does not speak in two voices.[1]”

Having been thus assured by Rāma, Kaikeyī said, “In the past, your father promised me two boons, when I saved his life during the battle between the devas and asuras. I have now sought them. I want Bharata to be anointed using the preparations already made and you should leave for Daṇḍakāraṇya right away – live there for fourteen years like a hermit, with matted hair and clad in barks of trees. If you wish to make your father’s promise come true and want to keep your word, decline your consecration and leave now!”

Even upon hearing these deadly words, no sorrow seized Rāma’s heart nor did his face betray anguish. Rāma declared, “So be it! I will leave for the forest right away in accordance with the king’s promise. However, I would still like to know why the king does not greet me gladly, like he did in the past! In fact, I would gladly offer Sītā, the kingdom, and my own life to Bharata. Would I resit when I have been asked to do so by my father, especially to please you. But, why does father gaze at the floor letting down tears? Let messengers go right away to fetch Bharata from his uncle’s place. I shall go straight to Daṇḍakāraṇya and stay there for fourteen years.”

Thrilled, Kaikeyī said, “You may leave right away, Rāma. Out of his embarrassment, the king does not wish to speak. Until you leave, your father will not bathe or eat!”

“Fie! Awful!” the king exclaimed and fell on the couch in a dead faint.

Like a horse whipped by its lash, Rāma made haste to leave. He said, “I am not after worldly pleasure, devi! You must know that I am like a ṛṣi in my adherence to dharma. There is no greater dharma than serving one’s father and adhering to his wishes. Though my father has not told me directly, I will live in the uninhabited forest for fourteen years. I will bid farewell to my mother, convince Sītā to stay back, and leave for the forest. Please ensure that Bharata rules the kingdom and serves my father.” Daśaratha wailed out loud. Bowing down at the feet of the unconscious father as well as Kaikeyī, he went in a pradakṣiṇa, Rāma, who glowed with splendour, walked out of the king’s palace. Enraged and his eyes filled with tears, Lakṣmaṇa followed him. Rāma performed pradakṣiṇa to the objects of anointment. Just as the darkness of the night does not diminish the brightness of the moon, Rāma’s radiance was not dimmed, though he had lost the throne. His mind could withstand all sorrows and his senses were under his control. He entered his residence without betraying his feelings on his face, lest the lives of his loved ones, who were now in merriment, would be endangered.

To be continued...

[The critically constituted text and the critical edition published by the Oriental Institute, Vadodara is the primary source. In addition, the Kannada rendering of the epic by Mahāmahopādhyāya Sri. N. Ranganatha Sharma and the English translation by Sri. N. Raghunathan have been referred.]

[1] i.e., does not go back on his word. This is the famous phrase rāmo dvirnābhibhāṣate (R. 2.16.24)