The first edition of The Karnataka contained a long form essay by Aluru Venkata Rao, popularly known as Karnataka Kulapurohita (High Priest of the Kannada Family), on the topic of the unification of Kannada-speaking regions. This apart, no less than Diwan Rangacharlu himself wrote a learned critique on the functioning of the Muzrai (Hindu Temple administration) Department. Other articles included analyses of the Government’s administrative machinery, various aspect related to social reform, and reports on the working of the Legislative Assembly.

In many ways, the first issue gave a foretaste of what the public could expect from The Karnataka, and DVG exceeded those expectations issue after issue. In fact, his lead editorial in the first issue made his stand quite explicit. It can be encapsulated as follows. The paper would:

· Champion the greatness of Indianness (Bharatiyata)

· Stimulate and encourage patriotism

· Carry the torch of national unity that was lit by the freedom movement throughout India and write on its importance and urgency for the Mysore State as well

· Instill a sense of purpose, direction, vigour and enthusiasm in all matters connected with public life in the Mysore State

· Foster healthy public opinion among all sections of the society

· Fearlessly condemn wrongdoing by anyone, anywhere

· Deliver news truthfully and in a timely fashion

In a sense, The Karnataka and DVG were inseparable—the young editor was the paper. It was fired with and blazed the passionate zeal of a future seer and sage who had discovered his life’s calling. And it singed the powers that be in an era where people in high office were unused to being scrutinized. Perhaps for the first time in its recent history, a journalist had actually dared to dissect the speeches of the Diwans—the de facto rulers—with pitiless honesty, a practice he applied to other high officials across various departments as well. Apart from this “insolence” of having the gumption to even question these administrative non-questionables, DVG’s phraseology also stung. For instance, when a certain Subrahmanya Iyer was appointed as a probationary to the Law Department, DVG wrote that he had “entered through the backdoor.” Mr. Iyer was unqualified for that important post: he had flunked his B.A. thrice in a row, had not practiced law even after passing his B.L. Thus, there was every possibility that this post was a reward for the services that his father or grandfather had rendered to the Government.

The summary[1] of this relentless badgering can be read in DVG’s own words:

What we now see everywhere is noise. Talk to any person and the talk is only about conferences and committees. Speeches and discourses are emanating from the mouth, not from the heart. It is not easy to distinguish whether the bluster about patriotism and service to people is simply because they are tasty to the tongues of these speech-givers or whether they are lights genuinely shining in their minds. The wise man must always be a man of few words.

In fact, The Karnataka did not spare even Diwan Visvesvaraya’s administration. The Diwan’s officials routinely began to pour the molten lead of complaints and tirades in his ears against the paper. Some senior bureaucrats who DVG knew personally told him in so many words: “You are not Karnataka, but Karkotaka,” an extremely dangerous poison. In turn, Diwan Visvesvaraya frequently told DVG, “You have become a very virulent critic.”

Indeed, when we read these sucker-punch-like criticisms of DVG, we’re reminded of the immortal lines of advice[2] given by Polonius to his son:

Be thou familiar, but by no means vulgar.

Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried,

Grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel;

But do not dull thy palm with entertainment

Of each new-hatch'd, unfledged comrade. Beware

Of entrance to a quarrel; but being in,

Bear't that the opposed may beware of thee.

Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice;

Take each man's censure, but reserve thy judgment.

This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.

In his characteristic style of introspection, DVG lists three chief reasons for these recurring clashes between The Karnataka and the Mysore Government:

- The British Resident who despised the paper’s strongly uncompromising nationalistic stand wrote repeated letters to the Government recommending[3] it to severely punish The Karnataka.

- Pressure from certain self-interested cabals in the Mysore Palace who hated Diwan Visvesvaraya. They went so far as to spread the rumour that The Karnataka was actually run by the Diwan himself.

- Critiques in The Karnataka regarding Diwan Visvesvaraya’s economic policies, especially his approach towards public spending and the establishment of the Mysore Economic Conference. In DVG’s view, both these were a drain[4] on the exchequer.

The truly august man that he was, Diwan Visvesvaraya never uttered a harsh word against the paper or DVG. Instead, he would personally invite DVG and discuss the criticisms at length. He would patiently listen to the young editor and seek clarifications where required. With the benefit of historical insight, it is quite clear that Diwan Visvesvaraya was the appreciative receptacle of DVG’s work in public life, his gentle mentor, and the protective cushion that both guarded The Karnataka and spurred it to newer heights.

****

In spite of these periodic hassles and other professional hazards, The Karnataka grew from strength to strength. Its acclaim, credibility, popularity, and the unimpeachable integrity of its editor had made it a household name by mid-1914, just over a year of launching it.

Thus, DVG’s friends and well-wishers advised him to start a Kannada edition of the paper, which he did on June 6, 1914. Some of the pieces that it published are notable:

· A long form profile of Bindiganavile Venkatacharya, a prolific novelist and an early translator of Bengali classics into Kannada.

· A glowing eulogy to Lokmanya Tilak

· A Kannada translation of Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor

· Robert Browning’s poem, The Pied Piper of Hamlin

However, this paper ran for just a few months and had to be closed owing to tepid public reception.

***

In 1915, DVG came under the profound spell of Gopala Krishna Gokhale, as described on several occasions in the earlier chapters. What is relevant here is Gokhale’s renowned dictum that public life must be spiritualised. These five words had such a lasting impact on DVG that he gave a new tagline to The Karnataka issue dated February 23, 1916. It now read: Devoted to the Cause of National Progress: Public Life must be Spiritualised. This tagline would carry over to the Public Affairs journal that he started in 1946. It also remains the tagline of the Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, Bangalore.

The Karnataka’s Dénouement

Two major events in the public and political space of the Mysore State around 1920 became the pivotal milestones in DVG’s life as well. Both occurred almost concurrently.

The first was the resignation of Diwan Visvesvaraya in 1919 on moral grounds. The second was the formation of the Praja Mitra Mandali and its political outgrowth, the Praja Paksha. The Praja Paksha took its inspiration from the ruffian-like political tactics of the Justice Party in the Tamil speaking regions. Both were premised on an especially vicious targeting of Brahmins, who became a marked community. Both events have been described at some length elsewhere[5] in this work.

It is best to read the consequences of both these events in DVG’s own[6] words.

Not once did Diwan Visvesvaraya ask me, “From where did you get this news? Who is your reporter? Who actually wrote this article.” On the contrary, he said, “I respect your independence and self-respect. But consider my difficulty. This large bludgeon—the Press Law…I can’t touch it. I keep getting pressure from various quarters to use that bludgeon against your paper. What am I supposed to do? What would you do if you were in place? Show me the way.”

Sri Visvesvaraya was a great man by birth. It is fundamentally against his nature to inflict injustice and pain. Not once did any bitterness arise between us due to my paper. It was an immensely pleasurable and joyous duty to run the paper during the tenure of such an exalted personality…

Competent officials are those who can tolerate blunt and fierce criticism. When incompetent and petty-minded officers occupy positions of authority, the profession of journalism becomes joyless. After the Praja Paksha was formed in Mysore, I felt that it was best for me to stop “The Karnataka.”

The trail of pioneering national and public service that The Karnataka had blazed in 1913 came to this abrupt, unfortunate halt in 1921. The total amount that subscribers owed to the paper at that time was around eight thousand rupees.

The Indian Review of Reviews

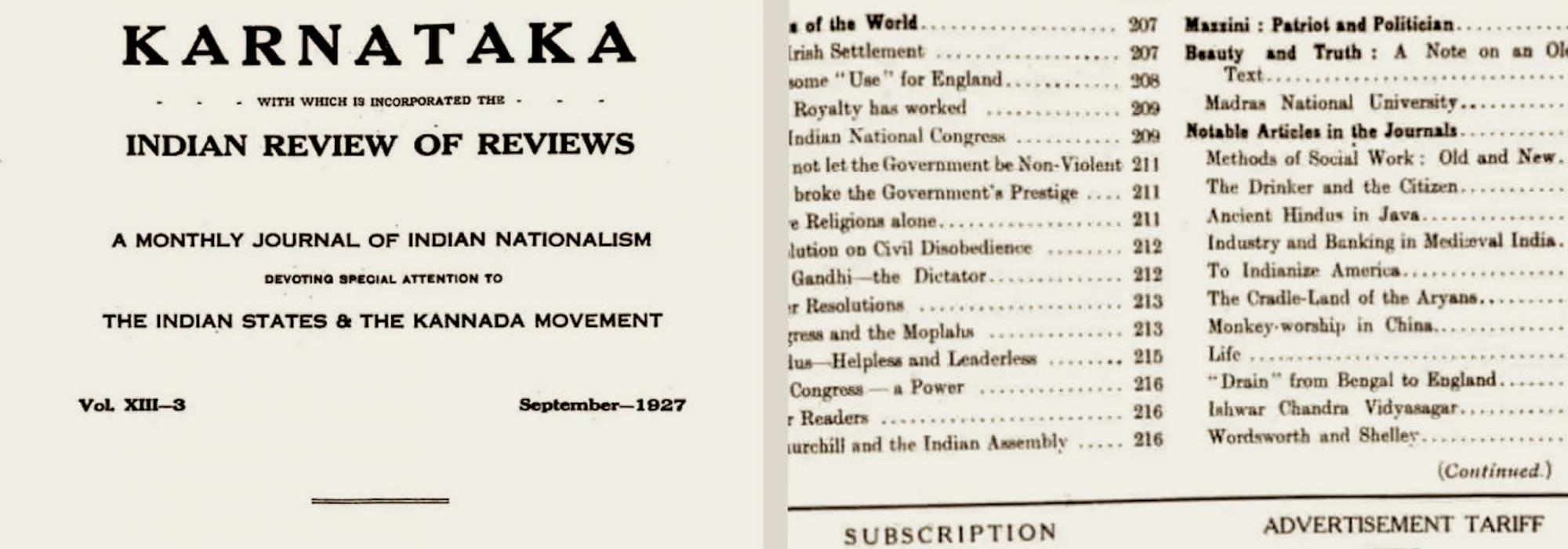

Later in the same year, DVG yet again, started a monthly, The Karnataka and the Indian Review of Reviews modelled after the legendary W.T. Stead’s Review of Reviews. Its archives remain a collector’s treasure for the breathtaking array of the topics it covered, the quality of its analyses and the wealth of insights they contain. Opinion pieces, independent essays, book reviews, profiles, historical essays, literary pieces, and articles on major national and international events formed its staple diet. Its annual subscription cost was ₹ 8 within India and ₹ 10, “foreign.” It also offered a carrot for advertisers in the following verbiage:

This journal circulates throughout India and among all classes of readers, and is expected to be permanently preserved and frequently referred to. Hence, it furnishes an excellent and unique medium for advertisement.

Perhaps owing to his experience in outstanding subscriptions at The Karnataka, DVG printed the following text in large capitalization in Indian Review of Reviews: ALL PAYMENTS TO BE MADE STRICTLY IN ADVANCE.

However, even this was not meant to be. Similar to his previous venture, The Indian Review of Reviews too, attracted enormous praise, respect, and admiration in all circles. Its articles were read with great interest by the various Maharajas, Diwans, judges, and scholars throughout India and copiously cited. However, all of this did not pay DVG’s bills.

The Indian Review of Reviews ran sporadically before being shuttered in 1927.

The Financial Side

A few incidents narrated[7] by DVG himself reveal both a pragmatic and rather touching picture of the financial side of DVG’s publishing endeavours.

Ganapathi Agraharam Annadhurai Ayyar Natesan, who ran the highly successful publishing house, G.A. Natesan & Co from Madras, was among the many prominent public personalities close to DVG. The Indian Review, a popular monthly which he founded and edited was not only highly respected but brought him fortune as well. Once when he visited “Right Honourable” V.S. Srinivasa Sastri in Bangalore, he took keen interest in DVG’s The Indian Review of Reviews. This was the conversation between Natesan and DVG:

“You are truly brilliant. You work so hard and your journal is of high quality. But in money matters, its business side is really pathetic. If you don’t garner advertisements and continue in this fashion, you will drown.” After this, Natesan proceeded to give valuable lessons to DVG on the methods of getting advertisements, and the tactics of improving revenue. Srinivasa Sastri who listened to this with great interest, finally said to Natesan: “Hey Natesha! Why are you telling him all this? You’ll never forget these lessons but he’ll never learn them. He believes that success in business is a sin. It is his fate, let him undergo it.”

Then, there was the other episode at Hassan. DVG had accompanied Srinivasa Sastri on a tour to the district. A visitor who had come to see Sastri spotted DVG, took him aside and said, “I owe you subscription dues for three or four years. I must confess that I kept forgetting to send you the money. And now, the moment I saw you, it struck me once more. Here, please take this now. I think there’s twenty-three rupees in this bundle of notes. If there’s shortfall, please write to me, I’ll send the rest.” This was DVG’s reply: “But what was the hurry for this? Keep it with you for now. I’ll look at the accounts once I return to Bangalore and write to you. You can then send me the exact amount.”

Venkatasubbayya, who was part of the entourage was livid when he saw this. He scolded DVG: “Bewakoof! You fool! You returned the money that was legitimately due to you.”

Srinivasa Sastri chipped in with his own diagnosis: “Useless sir, useless! Money does not stick to his hands. This level of stupidity! How much did he owe you?”

DVG: “Thirty-two rupees. Subscription for four years.”

Srinivasa Sastri: “Instead of taking what was offered, you said ‘you’ll see the accounts.’ You fat-cat!”

The other episode relates to a proposal DVG mooted in a letter to C. Rajagopalachari after the close of World War 2. The proposal was to start a new, niche journal devoted to exploring the various aspects in the aftermath of the war: efforts at preventing another such war, formation of international bodies like the United Nations, the Atlantic Charter and so on.

Rajagopalachari’s reply[8] of admonition was just one line: “Don’t. You have burnt your fingers enough!”

Recalling this incident much later, DVG’s notes: “I suppose some divine voice made me accept this advice. Else, I wouldn’t have been around to write this.”

***

As we have seen in detail in an earlier[9] chapter, DVG’s last and the most successful publishing venture was the Public Affairs journal which he ran till he shed his mortal coils.

To be continued

Notes

[1] Quoted in Virakta Rashtraka: D.R. Venkataramanan, Navakarnataka, Bangalore, 2019, p 63

[2] William Shakespeare: Hamlet, Act 1 Scene 3

[3] A highly representative incident of this hostility is the behavior of Henry Cobb, narrated in an earlier chapter.

[4] In his mini-biography of Diwan Visvesvaraya written much later, DVG seems to have revised his view. Here, he says that Diwan Visvesvaraya’s approach to public spending was premised on the creation of national assets, which would be beneficial to the State in the long run—say, after twenty or thirty years. As for the Mysore Economic Conference, DVG’s stance remains unchanged. This had less to do with Diwan Visvesvaraya’s farsighted vision behind it and everything to do with the caliber and attitudes of the people who populated it.

[5] See Chapters 6, 7, and 8

[6] D.V. Gundappa. Sankeerna, DVG Krutishreni, Vol 11, Government of Karnataka, pp 236-7. Emphasis added.

[7] D.V. Gundappa. Nenapinachitragalu - 2, DVG Krutishreni, Vol 7, Government of Karnataka, p 447

[8] Ibid. p 450

[9] Chapter 7