To be sure, recognizing DVG’s proven expertise in the subject, the Mysore Princely State requested DVG to put forward arguments on its behalf before the Butler Committee. But much before the actual meeting took place, DVG had already written a critique noting that its Terms of Reference[1] had a lacuna.

When the Committee met, a member, Holdsworth had this question for the Mysore State: “You said that once the citizens of the Princely State are granted constitutional rights, the responsibility of the British Government ends. However, when the people of the state do not carry on the administration effectively, shouldn’t the British government step in?”

DVG: “The citizens here are aware of their own interests much better than others. If they commit an error due to lack of experience, they will correct themselves. This self-education is also an organ of Responsible Government.”

Butler & Holdsworth: “So you say that Responsible Government is the best among all administrative methods?”

DVG: “Isn’t this the same view of British Parliament? How can that administrative system which is regarded as the best for the British, be improper for British India? Of late, we have the instance of H.G. Wells and others critcising British democracy. In spite of that criticism, my faith in the British system hasn’t diminished.”

Sydney Peal: “Do you mean to say that all the subjects of all Princely States should become part of British India?”

DVG: “I did not say that. My argument is that the people of the Princely States are deserving of the rights available to the citizens of British India. Taking cognizance of this is an important step in the direction of the country’s constitutional reorganization.”

This is but a mere tidbit[2] of DVG’s political prowess both within closed-door committees and outside. Both in theory and practice. We observe the same prowess in his critiques of the Chamber of Princes and the Council of Princes.

The Chamber of Princes or the Narendra Mandal was an overarching institution established by the royal proclamation of King George V in 1920. It was originally meant to be a platform where the rulers of the Princely States could voice their needs, aspirations and present their problems to the colonial Government of British India. In hindsight, the formation of the Chamber appeared to be a major breakthrough in the relationship of the British crown with the Princely States. Until its formation, the British crown kept the Princely States isolated from one another and also from the rest of the world. This policy was among the major points that DVG condemned the British policy towards the States when he said that “the character of Native States has baffled the classificatory skill of all writers on international law.”

The first meeting of the Chamber occurred on 8 February 1921 and from then onwards, met once annually with the Viceroy presiding. The Chamber convened at the Sansad Bhavan, which is today the Parliament Library.

In the first meeting, the Chamber comprised only 120 members. Of these, 108 members hailed from the significant states. The remaining twelve seats were for representation of a further 127 states. This meant that a whopping 327 seats were left unrepresented due to various reasons. A key reason was the refusal of some states to join the Chamber. These states included the powerful kingdoms of Baroda, Gwalior, and Holkar. Till the Chamber of Princes was finally disbanded in 1947, its meetings, operations and its entire trajectory was largely chaotic resulting in precious little good.

The final essence of these critiques of DVG with regard to the Chambers and Councils lies in his own call for federalism[3] as “the only principle” to end the “peculiar feature” of the people of the Princely States who had “a double government, a double allegiance, a double patriotism.” Even worse[4],

…in India, there is no authority, moral or legal, to which an injured Native State may appeal for redress as against the agents of the Supreme Power, who are far removed from the scrutinizing eye and controlling hand of the Parliament. The laws that govern the relations of the Government of India with the Native States are not fixed or defined; and the Governor-General’s powers in this matter are almost unlimited.

DVG thus envisages his federalism as a system that has a States’ Council “expressive of the general will of our Native States.” He is also cautious and aware of practical realities when he says that this States’ Council must not be equated with the “Upper House of any country.” And then he unambiguously delineates[5] its exact character and function:

…the States’ Council of India will stand by itself, speaking for a territory and a population quite different from those which find their spokesmen in the Governor-General’s Legislative Council. This diversity of the interests represented respectively by the two legislative and advisory bodies of India is only…to recommend their simultaneous constitution, inasmuch as either of them could not by itself stand for all sides of India’s political life—whereas between themselves they could cover up the entire field of Indian interests.

This may be best described as an enlightened Federalism. Like we have observed numerous times earlier, this recommendation-cum-solution once again shows how DVG was steeped in the cultural unity and civilizational indivisibility of Bharatavarsha.

Neither does he stop at this.

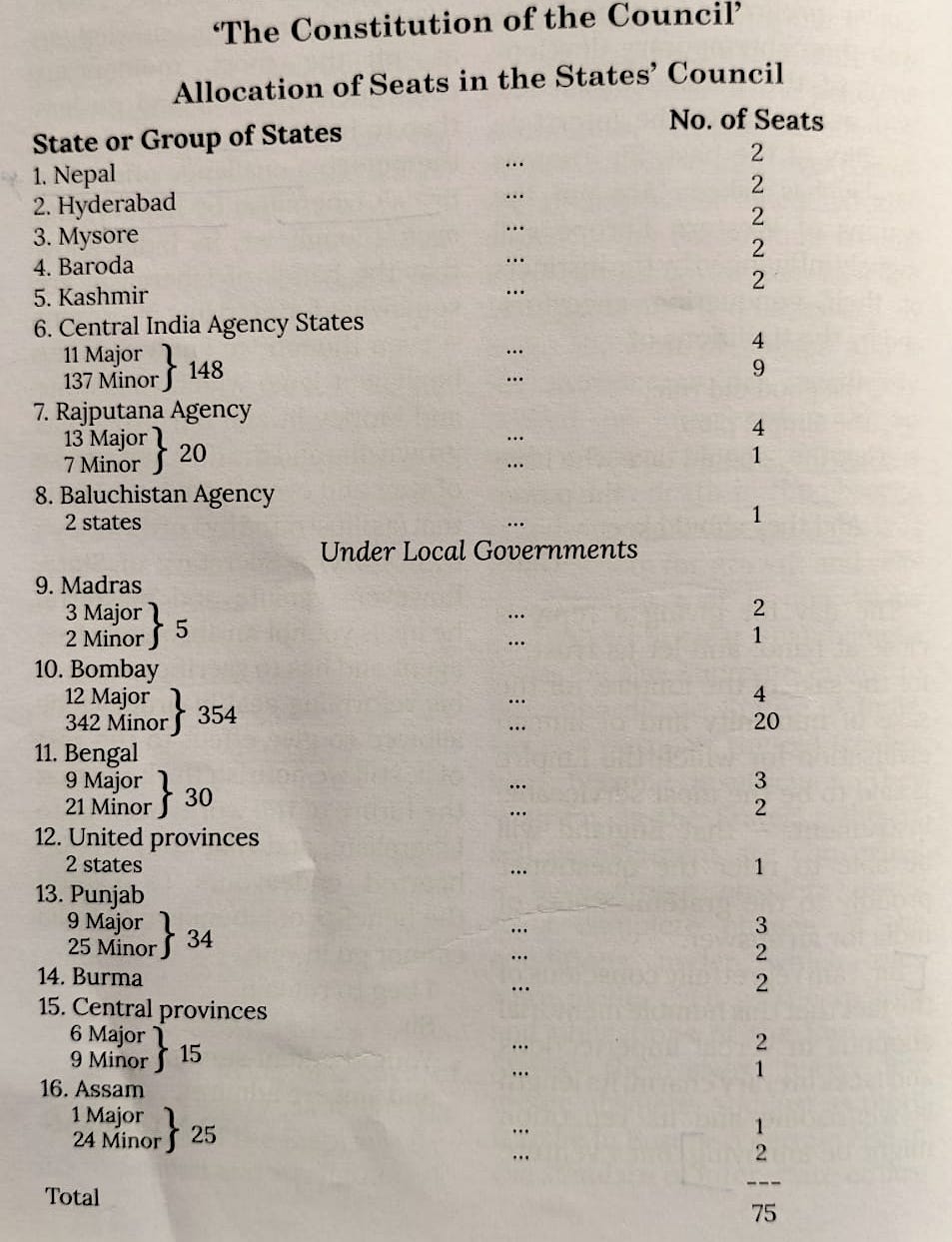

DVG offers both this theoretical background and practical working details of the States’ Council. Just as how we remarked in the first chapter that his Rajyashastra and Rajyangatattvagalu was a combined user manual to run the administration of an entire country, DVG’s treatise on the States’ Council could have ideally become a similar manual on sculpting a non-acrimonious harmony among British India, the Princely States and between the Princely States themselves. His vision of the States’ Council also includes a concrete working arrangement that he elaborates[6] in four steps and concludes with a draft Constitution of the States’ Council. Here are some highlights[7] of this Constitution.

As to its numerical strength, it may bear to the British Indian Supreme Council the same proportion that the Senate bears to the House of Representatives in the Australian Commonwealth: 1 to 2. Taking the number suggested by the [Indian National] Congress as the proper standard for the British Indian Council—namely 150, the membership of the States’ Council may be 75 strong.

The climax of DVG’s tour de force is a visual chart titled, The Constitution of the Council in which he computes the allocation of seats in the States’ Council as follows:

Finally, DVG once again throws[8] the ball of conscience in the British court when he says that the formation of the States’ Council—or in general, any arrangement that harmonises the diverse and disparate conditions of India as a whole—was a “challenge offered to British liberalism by history.”

****

Like notable tragedies in DVG’s illustrious life, his three-decade-long advocacy of the Princely States with a view to concordantly blend them into British India thereby reuniting an ancient civilization, ended in failure. DVG valued the Princely States as a civilizational good irrespective of the pit their rulers had flung them into. These States were the harbingers and the upholders of all that was noble, virtuous and valuable in the Sanatana spiritual and cultural tradition.

The world of the Princely States had irreversibly changed for the worse by 1947. As DVG himself notes later, the slackening had begun much earlier in his beloved Mysore State itself, roughly after Mirza Ismail became the Diwan, as we have seen earlier in this chapter. The State’s grip over the administration had weakened and the forces of mindless agitation heightened divisiveness. If this was the condition in a state ruled by a Rajarshi (Sagely King) like Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV and genuinely constitutional monarchs, the situation in other states were much worse.

Thus, when the Ministry of States[9] was established in May 1947 to deal with the integration of the Princely States in the soon-to-be-independent India, it was just a matter of time before the final denouement.

The Ministry of States was also the last leg of DVG’s attempts to somehow salvage the position of and stress the value of the Princely States to the citizens of the newly-independent Republic of India. In this, he directly locked horns with Sardar Patel and his lieutenant, V.P. Menon.

To be continued

Notes

[1] H. Butler. Appointment of our Committee and terms of reference, Report of the IAN States Committee, p 5. https://dspace.gipe.ac.in/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10973/29648/GIPE-009152-01.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

[2] The account of DVG’s arguments before the Butler Committee is taken from Dr. S.R. Ramaswamy’s profile of DVG in Deevatigegalu, Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana, Bangalore.

[3] D.V.Gundappa. Federalism, the Only Principle, Selected Writings of D.V. Gundappa, Vol I, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, 2020, Bangalore pp 307

[4] Ibid, p 308. Emphasis added.

[5] Ibid, p 310. Emphasis added.

[6] For the full illuminating discussion on this topic, see Selected Writings of D.V. Gundappa, Vol I, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, 2020, Bangalore pp 304 – 315.

[7] Ibid, p 312

[8] Ibid, p 315.

[9] The Ministry of States or the States Department was the new avatar, or a mere renaming of the British Government’s Political Department which was in charge of administering the relationship of the British crown with British India and the Princely States. The Political Department exercised its power on the basis of paramountcy as long as the British ruled India.