Half of the extant Mahābhārata is dedicated to dharma and ethics. In the other half, the main story and the upākhyānas are present. Even if we consider the latter alone, without doubt, it qualifies for a matchless poem. “कृतं मयेदं भगवन् काव्यं परमपूजितम्” (I have composed a sublime poem, O revered one!) says Vyāsa to Brahma. It is indeed poetry; doubtless it is sublime poetry; it has uniqueness in content, variety of characters, richness in emotions, a flood of rasa and a close examination of human life – where else in later literature can we find such quality? The epic does not contain kavisamayas (poetic conventions), literary acrobatics, diversity of chandas (meter) and overuse of embellishments; these have made their way into later poetry and it has only made it artificial, removing life out of it. In the epic, embellishments and descriptions are pleasing and optimally employed to enrich the circumstances. Due to our excessive familiarity with the works of Māgha and Śrīharṣa, as well as campū compositions, we have grown so accustomed to their artificiality that emotionally rich and natural poetry appears bland. Thus, later literary aestheticians and scholars do not consider it worthy to quote examples from the Mahābhārata, let alone praise its literary value. This was, however, not the case earlier. Bāṇa (c. 650 CE) hails Vyāsa as Kavi-brahma (the Poet-Creator). Just as Brahma created the land of Bhārata, sanctified by the flow of the river Sarasvatī, Vyāsa created the epic Bhārata sanctified the flow of his language – thus, Bāṇa expresses his adoration and admiration for the seer-poet. Kṣemendra (11th century CE) similarly hails Vyāsa as Kavi-brahma and also as ‘Pīyūṣa-rasa-sāra’ (the provider of the immortal rasa). The famous scholar of poetics, Ānandavardhana (c. 850 CE) praises the Mahābhārata by saying that although it is a treatise with a shade of śāstra-kāvya (a poem that educates people in the śāstras), it is a sublime and excellent dhvani-kāvya (poetry with profound suggestions) bringing out the śānta-rasa in a beautiful suggestive manner (udyota 4, kārikā 109).

Mahābhārata is a treasure house of stories; there is immense diversity in the sub-plots – stories of deities, demons, heroes, chaste wives, birds, snakes and other creatures; stories from the Purāṇas; tales of virtue and ethics; saga of ṛṣis, sages, selfless people, yogis and people who have found peace; stories of the ferocious and so on; these form the raw material for the later Sanskrit and regional language literature. It has made its way into a few literary works outside India and has gained immense popularity.

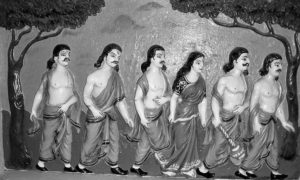

In spite of this, Mahābhārata is not a work that swells the mind with joy or makes it rejoice; pathos is its undercurrent (such is the conclusive statement of the Sāṅkhya school of philosophy – “तस्मात् दुःखं स्वभावेन” [Thus, pathos is natural] – Sāṅkhyakārikā 55). As it is the story of a war, it might appear as a work predominant in vīra-rasa, but in its backdrop lies the trials and tribulations of the Pāṇḍavas; what happens in the epic is the destruction of the lineage of Kauravas and Pāṇḍavas; the death of thousands of kings; the annihilation of the eighteen-akṣauhiṇi army. It is hard to say what kind of pleasure the Pāṇḍavas gained after facing so much of difficulties, losses, and pain; there is no description of that; soon, they leave for their great journey and reach the heavens. Upon reaching there, Yudhiṣṭhira is placed alongside Duryodhana, Karṇa and Śakuni! Their fight and death on the battlefield was enough to grant them the position!

Among women, it looks only Draupadī went to the heavens along with the Pāṇḍavas. Although she did not fight the war, she instigated, humiliated and coerced the heroes to fight the battle, giving them no time to even catch their breaths. Well, we shall say that it was proportional to the tribulations that she had to suffer! And did Kuntī not face trouble? Didn’t Ambā, Ambikā and Ambālikā face trouble? But none of them was as vocal as Draupadī! None of them was so fiery; ‘If there is a real man in the Mahābhārata, it is Draupadī’, thus someone has said. Thus, although she did not lose her life in the battlefield, she joined her husbands in the vīra-svarga (the heaven reserved for the courageous). The rest of the women had met their end in the pyre or in the forest.

Even though the stories like Nalopākhyāna, Sāvitryopākhyāna, Rāmopākhyāna and others end on a happy note, the background stories for a large part are not free of sorrow. Therefore, like Ānandavardhana says that upon reading the Mahābhārata in full, the sentiments that arise and that should arise are vairāgya (detachment) and śānti (peace). Kṣemendra says the same thing:

रत्नोदारचतुस्समुद्ररशनां भुक्त्वा भुवं कौरवो

भग्नोरुः पतितः स निष्परिजनो जीवन् वृकैर्भक्षितः ।

गोपैर्विश्वजयी जितः स विजयः कक्षैः क्षिता वृष्णयः

तस्मात् सर्वमिदं विचार्य सुचिरं शान्त्यै मनो दीयताम् ॥

[The Kaurava, i.e., Duryodhana who ruled the land between the four oceans, fell down with a broken thigh; with nobody beside him, he was eaten by wolves even as he was alive; the world conqueror Arjuna was defeated by a few cowherds and Vṛṣṇis destroyed each other; therefore, contemplate on this deeply and give your mind to peace.]

If peace is to be attained, it is by wisdom and adherence to dharma.