Dharma and Nīti (ethics) in the Mahābhārata

Dharma is that which sustains and supports the world; that which upholds; that which nourishes and protects from destruction. It is the root of peace and order in the world. We infer this mainly from the behavior and words of the epic characters as well as from the various stories and dialogues of the Śānti- and Anuśāsana-parvas.

Dharma is classified as sāmānya-dharma (fundamental values relevant to everyone at all times), varṇa-dharma (rules specific to various varṇas), āśrama-dharma (principles applicable to the various stages of life), āpaddharma (exceptions allowed during emergencies), mokṣa-dharma (the path to be followed for the conscious realization of eternal Bliss), rāja-dharma (rules and regulations for kings) and so on. Rāja-dharma comes under the broad umbrella of varṇa-dharma. However, as the expounder and the listener are both Kṣatriyas, it is elaborated. The discussion on mokṣa-dharma is contained in the section on Sāṅkhya-yoga, which will be dealt with later. Sāmānya-dharma is today considered as mānava-dharma (human values).

In today’s context, ‘king’ implies government; even where there is a ruling king, he must be must be amicable to the government. Today, politics and administration are corrupt; They have surpassed the evil Kaliṅga-Nīti; however, what they have to primarily keep in mind is “taking care of the citizens is the essence of rāja-dharma” and “The king is the maker of time” (राजा कालस्य कारणम्); however essential the support of the citizens may be, not much can be achieved by the citizens who lack the nourishment of the government machinery; ethics are constant.

In countries like India, kings are disappearing and democracy is making an entry, the atrocities committed by the kings to selfish ends and their indiscriminate acts are also on their way out [circa 1950]. However, what the king wanted for himself, now the citizens are seeking it for themselves, for their region, for their state and for their nation. Therefore, regionalism and nationalism are on the rise. It is the same whether a king develops hatred towards another king that results in a calamity, or a leader harbors animosity against another, or a nation develops enmity towards another, resulting in nasty politics, war and destruction; it is the common man who suffers. When a husband and wife fight, it is the innocent child that is affected, as is well known.

With today’s socio-economic conditions, with people taking up various professions, it is becoming difficult to hold on to varṇāśrama-dharma. Since long, the varṇas have intermixed and lost their exclusivity (See the

Ajagaropākhyāna). Today’s problem of varṇa (which also means ‘color’) is of a different kind – red, brown, black, yellow – it is related to discrimination based on people’s complexion; there is revolution to get rid of these too; these differences will gradually vanish. [This is a reference to racism.] From the perspective of guṇa-karma (natural traits and actions/ professions), distinctions exist worldwide. They are not referred to as ‘varṇa,’ but as ‘varga’ (class); in the West, there is economic hierarchy between the aristocracy and the proletariat, the ‘upper’ and the ‘lower’, that has resulted in gains and losses in families and assets including the nation at large. Today’s problem is not that of a division based on birth, but an economic stratification of the society as poor and rich; these are the only two classes that have taken predominance. It has become difficult for the poor to live in the shadow of the rich; he has no access to higher education; he has difficulty to lead a respectable life with access to nutritious food, medical facilities during illness and general health and well-being to work hard. In the past, people belonging to all varṇas were able to manage their lives well; survival was not such a big problem. Everyone encounters problems and it comes to them as a function of their past deeds (karma) – such was the prevalent feeling leading to a certain level of contentment. The common man did not have any major problem in the past.

Just like the varṇas, the system of āśramas (stages of life) has become obsolete. Only a couple of āśramas are prevalent. We can say a word or two about the Gṛhasthāśrama, i.e., the ethics of a householder. We learn about this from Vidura’s constant ethical advice to Dhṛtarāṣṭra and even more prominently from the behavior of the prominent characters and the development of the story at large. Gṛhastha is a householder who runs a family. Here, family includes husband and wife, parents, siblings, children, relatives and friends. A family is the basis of society. In today’s economic conditions, since there is excessive emphasis on individual freedom, there is a reduction in commitment, loyalty, unity and other noble qualities associated with the family. What is a family without love? It is a desert, or it is a Kurukṣetra. If there is disharmony between people who are living together, it is like a thorn that has pricked and penetrated the foot; pulling it out results in a wound and leaving it behind causes pain; and one limps while walking. Pain constantly haunts a person and takes away his focus from work. If the pain needs to overcome, every person should limit his notion of personal freedom. Each has to compromise and sacrifice at least a little of his personal comfort for larger harmony and happiness; along with a sharp intellect, one also needs a certain amount of empathy and commitment. Even the deities possess these qualities. People of old age who are bereft of formal education and learning, have experiential wisdom and sagacity; bookish knowledge does not supersede experience; experience is the greatest teacher.

One who did not develop intellect by listening to the experienced may develop it from his own experiences. Waiting for the right experiences in one’s own lifetime and to attain wisdom only from those is not the quality of the wise; the reason being that such an opportunity might never arise in one’s life. If there is love in family life, forgiveness and magnanimity come naturally. These are the yardsticks of true love – the forgiveness we have for others’ mistakes, empathy for their troubles, and the attitude of taking care of their needs at the cost of our comforts. The example of the pregnant woman given to the king applies to everybody (see Śānti-parva). We see this kind of harmony in the Brāhmaṇa family who are saved from the clutches of Bakāsura. Sāvirtyopākhyāna, Nalopākhyāna and other such upākhyānas contain the invaluable portrayal of such love, affection and self-sacrifice.

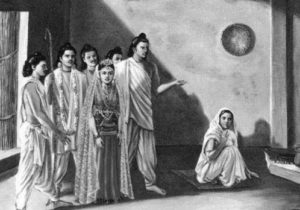

Even if we leave out the upākhyānas, it is sufficient to see Kuntī ’s family in the main story; she had such intimacy with her children! Did she discriminate between her own children and children of her co-wife, Madri? She was in fact partial to Sahadeva. Even her co-wife knew this; Kuntī knew what her children wanted even before they voiced it. Just take a look at the situation where the Pāṇḍavas leave the Ekacakra-nagara for the svayaṃvara of Draupadi. Such

camaraderie between the brothers! It is only they who could share a wife among five brothers and live without misunderstanding. Just because Arjuna won her in the svayaṃvara, he did not exercise right over her as the sole husband; even when Yudhiṣṭhira tells him so, he is not satisfied; Arjuna has the feeling that she equally belongs to all the five; (let us keep aside the past-life justifications and see the story as told by the poet!)

The main reason for all the five getting married to her is that nobody wanted the other to feel bad. Moreover, Draupadī too was attracted to all five brothers. Kuntī said, “All the five of you share!” perhaps with the idea that none should feel dissatisfied. Even as Draupadī enters their household, Kuntī gives her the charge and instructs her on various aspects of family life. Draupadī sacrifices her royal status, is obedient to her mother-in-law, and starts her family life in a potter’s house. Till the very end it is the same respect and affection they have for each other. Nowhere in the epic is it told that they had a fight. Draupadī had as much respect for Kuntī , her mother-in-law, as the Pāṇḍavas had for their mother. There was such brotherly love among them! It is only out of respect and affection they had for Yudhiṣṭhira that they could tolerate the troubles and tribulations wrought upon them by his deeds. Arjuna had taken a vow that he would destroy the person responsible for shedding even a drop of Yudhiṣṭhira’s blood; Yudhiṣṭhira too had taken an oath that if any of his brothers died in front of him, he would immediately take his own life. Even when he went to heaven, he was obstinate in demanding: “Without my brothers, I will not enjoy the joys of the heavens alone.”

Śantanu is embarrassed to bring up the topic of Satyavatī in front of his son; looking at his worried face, Bhīṣma finds out the reason from a minister of the king. In that episode, the subtle words of Śantanu and Bhīṣma’s courageous conduct are both worthy of praise. It is hard to decide whom to praise more – the father or the son. Finally, Bhīṣma makes a great sacrifice possible only to him, that is hailed as the best of its kind—unlike Pūru’s— becomes famous for his valor. “There is no prosperity now or beyond without a son; therefore, let my wife beget children from other men!” – while such was Pāṇḍu’s desperation, Bhīṣma said, “Even without children, I will attain heaven.” If I don’t attain heaven, so be it, let my father be happy; that is a great dharma. If he treads the path of dharma, he shall be prosperous here and beyond, he shall reach a higher realm than those who have children – such was the conviction of the independent thinking and manly Bhīṣma! What affection and devotion he had towards his father, his step-mother and their children. Did such devotion and respect diminish his stature? Did this reduce his capabilities and respectability? He shared half of the burden of the Mahābhārata war; he had great responsibilities towards both sides for he was the grandfather to them all.

When either one or both compromise in a family, will love blossom; only that relieves worry and trouble, leading to peace and happiness. Therefore, a person’s character, particularly sacrifice and forgiveness are important; and because of these, the family life becomes enjoyable. The foundation for this lies in love, affection, empathy, commitment, mutual respect, etc; all these are essentially the same; different shades of the same sentiment of friendship operate at different points in a relationship and take different names. If, thus, people evolve their emotional landscapes, family life becomes excellent; this is because ten individuals make a family, ten good families make a noble society; and from society are a state and a nation formed! Therefore, basic human values, family values and integrity of the individuals are very important. Goodness of the individual is the goodness of the nation. To nourish this goodness is the foremost responsibility of a king.

While discussing the traits of all the family members, the author of the Mahābhārata has laid emphasis on the good-nature of a wife. Draupadī’s words of insult aren’t to be criticized, for her words are nothing compared to the pain and humiliation that she underwent because of her husbands. Even with troubles in their families, it’s amazing to see the kind of love that Kuntī , Gāndhārī, Satyavatī, their daughters-in-laws, and Sāvitrī, Damayantī, and Kaikeyī had for their husbands. The story of Caṇḍi that appears in Jaimini’s Bhārata is nothing compared to these upākhyānas. If either the husband or the wife in a family is irresponsible, it’s as good as half the family succumbing to a disease; what peace can such a person get? Only suffering, and waiting for death. And if both husband and wife are of bad character, it is like two rams fighting atop a narrow bridge and both falling into the water as a result of their misdemeanor.

This is not a recent problem; and not limited to our country alone; the antidote that the West has found for this is divorce. This is a result of seeking individual freedom. This has become rather common among them but this hasn’t made them happier; because a divorce has several repercussions. This is not natural to our country and culture; it can utmost be an āpaddharma. A broken heart is like a broken pot that can never be put together again. It can’t be mended by adding new pieces. Those desirous of possessing an earthen pot must be careful in handling it. This is wisdom. As long as the husband and wife co-operate with each other will there be family life. There is no story narrated about a man with two wives with everyone living happily together. Even in the Mahābhārata, ultimately when Mādri has twins (with the help of Kuntī ’s mantra) it is said that Kuntī was upset. When such is the case, the story of the woman who happily co-habited with five husbands—without any misunderstandings between the husbands and the wife—shows the brotherly affection that the Pāṇḍavas had for each other and their love for Draupadī. However, Draupadī seems to have greater love towards Bhīma and Arjuna but not without reason. It is Yudhiṣṭhira’s opinion that she was partial to Arjuna. But we don’t come across any instance of such partiality expressed by Draupadī in her words or actions, resulting in disharmony in their family life.

It would be more appropriate to say “This way or that, Kuntī never had peace” instead of the popular “This way or that, Kuntī ’s children didn’t enjoy the kingdom.” From her birth until her death, Kuntī only suffered. And yet she displayed so much courage, forbearance, and fortitude! Man’s real nature comes to light only in times of adversity. And how Kuntī , Sāvitrī, Damayanti, Sītā, and others bore the difficulties without complaining or whining! The Mahābhārata shows that due to their wisdom, honesty, and adherence to dharma, they finally attain peace and happiness; they stand as examples for not only women but also to men.

Comments