After briefly referring to some commentators on the Gita—including Shankara, Ramanuja, Jnaneshvar, Tilak, Aurobindo, and Gandhi—Kosambi again raises the question as to how the same text could appeal to different people in different ways. He concludes his rant with these ridiculous lines:

“What common need did these outstanding thinkers have that was at the same time not felt by ordinary people, even of their own class? They all belonged to the leisure-class of what, for lack of a batter term, may be called Hindus.” [emphasis is mine]

(M&R, p. 18)

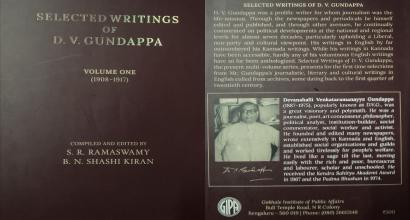

Before refuting Kosambi’s claims on this point, let us first take a look at the minds that the Gita has attracted: Humboldt, Schopenhauer, Emerson, Thoreau, Schweitzer, Jung, Hesse, Eliot, Huxley, and Oppenheimer, among others in the West; Tilak, Malaviya, Gandhi, Coomaraswamy, Rajaji, DVG, Munshi, Radhakrishnan, Nehru, Bhave, and Bharathiar among other Indians. The choice is eclectic yet this includes only the ‘secular’ minds. Our spiritual minds were almost unequivocally influenced by the Gita, starting from Shankara, Ramanuja, and Madhva to Jnaneshvar, Chaitanya and Ramdas to Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, and Aurobindo.

The influence of the Gita has not been limited to a single period in history or a single place in the world; it has not been bound to a single school of philosophy or a single sect of people. It transcends all boundaries and distinctions. [For those interested, there is a long list of quotations about the Gita from various sources in The New Bhagavad-Gita (pp. 325-33) by Koti Sreekrishna and Hari Ravikumar (Mason: W.I.S.E. Words Inc., 2011)]

The Gita is the most popular book from India and one of the most popular books in the world. There are at least a hundred commentaries on the Gita in Sanskrit alone. There are more than a thousand English translations. Apart from most Indian languages, it has been translated in several foreign languages as well. And this has only been increasing over the years.

Further, there are about forty gitas that were inspired by the Bhagavad-Gita including Uddhava Gita , Guru Gita , Rama Gita , Ganesha Gita , Ribhu Gita , Devi Gita , Avadhuta Gita , and Pandava Gita. Recent works like Satyagraha Gita, Sangha Gita, and Shrama Gita are also inspired by the Bhagavad-Gita. In fact, there are also parodies like Chaha Gita. And yet when one says Gita, it always refers to the Bhagavad-Gita.

It is rather strange that Kosambi should refer to them as a ‘leisure’ class when each one of the names he has quoted― Shankara, Ramanuja, Jnaneshvar, Tilak, Aurobindo, and Gandhi―were active members of the society pursuing a great ideal. It is unclear on what basis Kosambi confidently concludes that the Gita did not influence ordinary people (while it appealed to these ‘outstanding thinkers.’) [Note: In general, any form of art, science, or technology will be truly understood only by a small number of people; but the benefit will be accessible by all. For example, only musicians know the mechanism of producing good music but everyone can enjoy that music; only telecommunication experts know exactly how a mobile phone works, but everyone can use the device.]

Kosambi then tries to demonstrate how the laity and the bhakti poets thrived without the Gita. He says:

“...the great comparable poet-teachers from the common people did very well without the Gita. Kabir, the Banaras weaver, had both Muslim and Hindu followers for his plain yet profound teaching. Tukaram knew the Gita through the Jnaneswari, but worshipped Visnu in his own way by meditation upon God and contemporary society in the ancient caves (Buddhist and natural) near the junction of the Indrayam and Patina rivers. Neither Jayadeva’s Gita-govinda, so musical and supremely beautiful a literary effort (charged with the love and mystery of Krsna’s cult) nor the Visnuite reforms of Caitanya that swept the peasantry of Bengal off its feet were founded on the rock of the Gita.”

(M&R, p. 18)

Any student of philosophy knows that texts of universal wisdom like the Gita need not be formally read, just like one need not read Newton’s findings to acknowledge or comprehend gravity. [Note: In many later philosophers and writers – be it Spinoza or Kant or Voltaire or Mark Twain – we can see the wisdom of the Gita though they might not even have known of its existence.] Just because it is possible to understand the wisdom of the Gita without formally reading it does not make it a vestigial text. Kosambi himself calls Jayadeva’s Gita-Govinda a “musical and supremely beautiful...literary effort” – how does he hope to find philosophy in it? It is a poetic journey into Kṛṣṇa’s youthful love-life. Why should it be “founded on the rock of the Gita”? If one were to write a poem about the formative years of an M S Subbulakshmi or an Abdul Kalam, why should it have anything to do with the fact that they won the Bharat Rathna? And as for Chaitanya, he was a strong proponent of the Gita.

Further, what does a Kabir or a Tukaram say that is wholly different from the Gita? Knowingly or unknowingly most of our saints and mystics have echoed the wisdom of the Gita.

The Sangam poet Kaniyan Pungunranar (c. 5th century BCE) sings in the Purananuru (verse 192) –

யாதும் ஊரே யாவரும் கேளிர்

தீதும் நன்றும் பிறர்தர வாரா

நோதலும் தணிதலும் அவற்றோ ரன்ன

(http://ta.wikipedia.org/wiki/கணியன்_பூங்குன்றனார்)

"Every town is home, everyone is kin

Evil and good are not gifts from others

Pain and pleasure are our own doing..."

In the Gita, one of the traits of a bhakta is aniketah (BG 12.19) – one who considers no place as his home but feels at home everywhere. Pungunranar says the same thing with யாதும் ஊரே, which literally means: ‘which is my town?’ Krishna says in the state of brahman one sees the same atman in all beings; he sees oneness everywhere (6.29). People, not God, are responsible for good and evil in the world (5.15). One should advance by one’s own efforts and that the self is one’s true friend or enemy (6.5).

Here is an abhang (poem) by Tukaram (c. 17th century CE) –

Don’t kill a snake

Before the eyes of a saint

For the saint’s being

Includes all living things

And he’s easily

Hurt

(Tukaram. Says Tuka. Tr. Chitre, Dilip. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1991. p. 155)

See this in light of some Gita verses – 5.18 (A wise person treats everyone equally), 6.32 (A yogi relates to the joy and sorrow of others just as he relates to his own), and 6.9 (A yogi behaves in the same way with everyone – be it family, friends, foes, mediators, bystanders, saints, or sinners).

A famous doha (couplet) from Kabir (c. 15th century CE) goes thus –

कबीरा खड़ा बाज़ार में, मांगे सबकी खैर

ना काहू से दोस्ती, न काहू से बैर

(http://www.shers.in/kabira-6296.html)

"Kabir is at the market; he wishes well for all

He seeks neither friendship nor enmity"

In the verses 14.22-25 of the Gita, Krishna speaks about such a detached person. He says that one who has gone beyond the influence of guna (innate qualities) remains unruffled and unattached. In 3.25, Krishna speaks of how the wise work for everyone’s welfare.

In one of her vacanas (free verse), Akka Mahadevi (12th century CE) says –

Till you’ve earned

knowledge of good and evil

it is

lust’s body,

site of rage,

ambush of greed,

house of passion,

fence of pride,

mask of envy.

(Ramanujan, A. K. Speaking of Śiva. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1973. p. 108)

She is basically referring to the ari-shad-varga (the six primeval enemies) of lust, rage, greed, passion, pride, and envy. Krishna refers to the same thing in the Gita – 16.21 (lust, rage, and greed are the three gates to degradation), 16.10 (the wicked are soaked in passion and pride), 4.22 (the wise ones are free from envy).

Contrary to Kosambi’s claims, the Gita had a wide-ranging influence on the laity. We see a reference to the Gita in popular literature as early as Kalidasa. In chapter 10 of Raghuvamsha and chapter 2 of Kumarasambhava, we find verses that are almost identical to that of the Gita. In the Hindu tradition, the Vedas were accessible exclusively by the men from the brahmana, kshatriya, and vaishya varnas. But for the sake of the education of women from all varnas and the shudras, the entire corpus of the Purana and Itihasa literature was composed.

Jnaneshvar’s 13th century commentary is one of the finest examples of the attempt of the learned to share the wisdom of the Gita with the laity. The Jnaneshvari is composed in a beautiful folk poetic meter called ovi, which was often used for composing lullabies. It is such a simple, down-to-earth meter. Why did Jnaneshvar choose that meter? It underscores his intent to share the message with everyone.

Under the patronage of king Raja Raja Narendra, the poet Nannayya Bhatta (1000-1060) started translating the Mahabharata into Telugu but died after working on two episodes. Many years later, Tikkana (1200-1280) translated 15 episodes and Erra Pragada (1280-1350) completed the work. Vedanta Deshika (1268-1370) composed a summary of the Gita in Tamil titled ‘Gita Prabandham.’ Madhava Panikkar prepared a condensed Malayalam translation of the Gita in the 14th century. Kumara Vyasa (Gadag Vīira Naranappa) rendered the Mahabharata into Kannada in his Karnata Bharata Kathamanjari, which was finished in 1430. The poet Nagarasa translated the entire Gita into Kannada shatpadis (six-line verses). Kabi Sanjaya translated the complete Mahabharata into Bengali during the first half of 15th century CE. King Lakshminarayan commissioned Govinda Mishra to translate the Gita into Assamese verse.

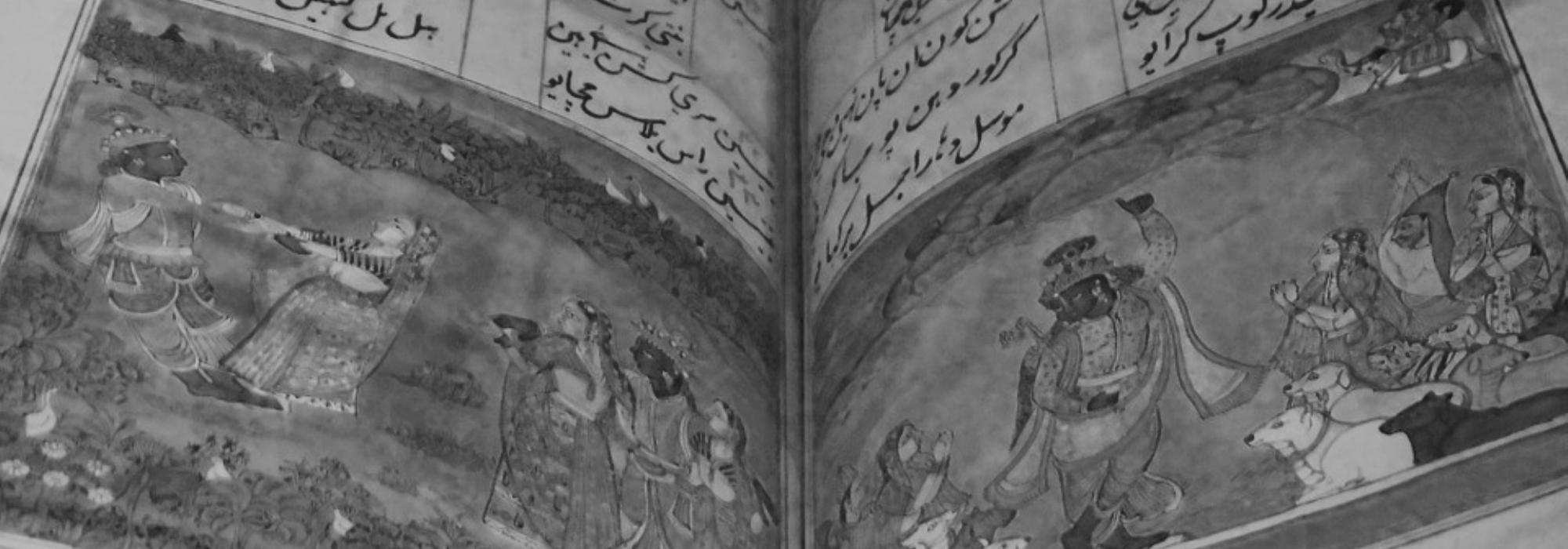

We can also see the influence of the Gita in the various music compositions, dance forms, folk poetry, paintings, harikathas (musical discourses based on traditional stories of various Hindu deities), and sculptures.